50 years later: Turcotte still speaks of his love for Secretariat

It is the golden anniversary of the most famous accomplishmentin the history of horse racing.

It was the spring of 1973. The spring of Secretariat.

It reached a crescendo when the big, chestnut colt was “movinglike a tremendous machine” in unthinkable, record time to complete the firstTriple Crown of the television era. It was a romance that galvanized Americansport, that resonated in an American culture that was smack in between Vietnamand Watergate.

Jockey Ron Turcotte had a head start of more than a year.

“Believe me, it was love at first sight,” he said. “Love atfirst ride.”

That was in January 1972, when trainer Lucien Laurin introducedthe 30-year-old jockey to the 2-year-old colt at Hialeah Park in Florida. Inthe next 22 months they would make the kind of history that felt then like itwas once in a lifetime. A half-century later it still feels that way.

“He was everything,” Turcotte said. “Somebody said thatthere will never be another Triple Crown winner. But there will be anotherTriple Crown winner, because they were saying the same thing when we went 25years. There will always be Triple Crown winners.”

After Secretariat ended the quarter-century wait sinceCitation’s 1948 sweep of the Kentucky Derby, Preakness and Belmont Stakes, and longafter he shattered track records with performances that have stood the test ofall this time, Turcotte would have none of the statement that Secretariat wasmaybe the greatest racehorse of all time.

“There’s not too many maybes there,” he said before he declared,“Definitely.”

From snow to sunshine

Eddie Sweat, 58, Secretariat’s hard-working groom, died in1998. Laurin, 88, in 2000. Breeder-owner Penny Chenery, 95, passed away in 2017.Big Red himself preceded them all, euthanized in 1989 at age 19 after he gotlaminitis.

Turcotte, 81, is the lone survivor among Secretariat’s mostprominent connections.

When Turcotte answered the telephone last month at his housein his native New Brunswick, Canada, the calendar said it was the first week ofspring. The stubborn climate of the Maritimes suggested otherwise.

“In the snow country,” he told Horse Racing Nation’s Ron Flatter Racing Pod. “I was born here. I went to school here. Then I worked inlumber for five years before I moved to Ontario and got lucky there.”

That was where Turcotte, the third oldest of 12 brothers andsisters, caught on first as an exercise rider and then as a jockey. And a goodone. As a bug boy 60 summers ago, he rode the debut win on Northern Dancer, whowent on to become one of the greatest stallions of all time.

Within a few years, Turcotte connected with Laurin, a fellowCanadian from Québec who worked as a jockey in the 1930s before beginning a 45-yeartraining career in the northeast U.S. during World War II.

“We had done a lot of fishing together,” Turcotte said. “We’reboth fishermen, and we got together in ’67 and ’68. Those were the two bestyears that Lucien and I had in Florida. When he came north, he picked up someother horses from some other stables. They had their own riders, so I toldLucien that I wasn’t going to just school horses for other riders or go workhorses for somebody else in the morning.”

Laurin took Turcotte with him and embedded him in the NewYork jockey colony. Laurin was pushing 60 and was pretty much retired when hisson Roger recommended him for some part-time training at the strugglingVirginia stable where he had been working. That was when Laurin and Turcottewere introduced to the Chenerys and their Meadow Stable.

The rising stars of 1972

A year before Secretariat, Riva Ridge won the Kentucky Derbyand Belmont Stakes. He lost the Preakness when rain turned the Pimlico trackinto slop he did not like. That unrequited Triple Crown of 1972 established theteam of Meadow, Laurin and Turcotte just as their new star was about to rise.

That first ride Turcotte had on Secretariat came four monthsbefore Riva Ridge won the Derby.

“I asked Lucien, ‘Who is that pretty boy you’ve got here?’ ”Turcotte said. “He told me, ‘He’s a Bold Ruler. Too good-looking to be true.’Then we went to see Riva Ridge. ... He asked me if I was ready to go to work. Isaid yes. I got my boots on. He said, ‘All right. Put your tack next to thatpretty boy and tell me what you think about him.’”

As Bill Nack wrote in his seminal 1975 book Secretariat:The Making of a Champion, Turcotte slowly galloped the ever-growing2-year-old in company with three other colts “almost lackadaisically.”

Turcotte’s memory 51 years later was more upbeat.

“He was so beautiful to ride, gallop,” he said. “He didn’tshy from anything. ... At that time he was still carrying a little baby fat,but he was still very good to gallop and all that the first time I got on him.”

An injury and another commitment kept Turcotte from ridingSecretariat’s first two races. Once they got together, it was magic.

“Coming out of the gate I never rushed him,” Turcotte said. “Ilet him take his time, and he’d come from way back.”

They finished first in all seven of their starts in 1972,although one resulted in a disqualification. No matter. Secretariat would becomethe first 2-year-old in two decades to be named horse of the year.

Riva Ridge might have come up a wet track short of being thechosen one, but Meadow Stable had the horse who was about to put thatfrustrating memory out of sight. And Turcotte was about to be along for theride.

False rumors and arace-day nap

In Australia the word is unbackable. It means a horse whoseodds are so short that it makes little sense to lay a big bet to get a tiny profitin return. By the time he began his 3-year-old season, Secretariat wasunbackable, returning no more than 60 cents on a $2 win bet for eightconsecutive races.

The last of those came two weeks before the Kentucky Derbyin the 1973 Wood Memorial, where co-owned Secretariat and Angle Light were acoupled 3-10 favorite. Inexplicably, Secretariat finished third to hisstablemate, inspiring what might have been the most grousing ever heard atAqueduct from successful bettors.

It is no secret now that Secretariat had developed a painfulabscess behind his upper lip. Nobody knew it on race day, though. Decadesbefore social media, the grapevine of rumors about the horse’s fitness was in fullflower.

“Especially after I worked him the following Saturday,”Turcotte said. “I didn’t like the way he went. I had flown down to Kentucky towork him. I had to go back (to New York), and I ran into Dr. (Manuel) Gilman.Dr. Gilman asked me if I had worked the horse. I said yes. He said, ‘How’d hego?’ I said, ‘Something’s wrong. I don’t know what it is. He hits the groundgood. He’s sound, but there’s something wrong.’ ”

That was when Gilman, a groundbreaking racetrackveterinarian who died in 2011 at age 91, revealed the problem to Turcotte.

“He said, ‘Did the abscess come to a head?’ I said, ‘Whatabscess?’ ” Turcotte said. “That’s when I found out about the abscess. Had I knownbefore, if Lucien would have told me before, I’d have rode him with a looserrein. He wouldn’t have been pulling his head, and I think he sure would havewon.”

Amid the churn of rumors, the abscess sounded to skepticalbettors like one more excuse. Secretariat was not unbackable in the KentuckyDerby. He still was favored, but he and Angle Light went off at 3-2, whichlooks now like the overlay of the century. Or at least the half-century.

On race day, May 5, 1973, Turcotte did something a littledifferent when he arrived at the Churchill Downs jockeys room. Rather than preparefor rides on the undercard, Nack wrote, Turcotte took a nap.

All these years later, Turcotte said it was not so much thathe was oblivious to all the pressure. It was about a local racing regulation.

“They had a rule in Kentucky that if you went down in a race,you were taken off for the balance of the day,” he said. “Therefore, if I geton a horse and he stumbles, he gets shut off and goes down or something, I automaticallycouldn’t have rode in the Derby.”

Turcotte said he got first-hand knowledge of the rule ridingthe previous spring at Keeneland.

“A horse died after we won,” he said. “He dropped dead of aheart attack or something. My foot was stuck in the iron. It took me a littlewhile to get loose. When I got on the scale, the clerk of the scale told me Iwas off. I couldn’t ride the rest of the day.”

That was the afternoon Riva Ridge raced in the Blue GrassStakes. Turcotte said he practically had to beg to keep the mount.

“Only after telling the stewards what exactly happened, andthat I was fine, and first aid had told them I was fine,” Turcotte said, “I gotto ride Riva Ridge.”

That ride was a winner, but the experience made Turcotte lesswilling to take any chances that he would not get to be paired with the horseof the year in the 1973 Derby.

Bad timing for a rival

The 2010 movie “Secretariat” played up the rivalry withSham, the California-based horse who won the Santa Anita Derby in a time thatstill stands as a stakes record. He also finished second in the Wood Memorial,ahead of Big Red.

The film made Sham’s trainer Pancho Martín out to be amouthy villain, but contemporaries do not remember him that way. On thecontrary, Turcotte had nothing but glowing things to say this spring about thehorse who finished second to Secretariat in the Kentucky Derby and the Preakness.

“Oh, he was a great horse,” Turcotte said, his voice turningwistful at the thought of him. “Sham was a great horse, and any other year he’dhave won the Triple Crown. He was breaking records right alongside me. I wouldbreak the track record, and Sham also broke the track record.”

Sham was the 5-2 second choice in the Derby, and he finished2 1/2 lengths behind Secretariat, clearly the best of the rest of the field. Secretariat’stime was 1:59.4, still a Derby record. If a length is roughly equivalent to one-fifthof a second, then Sham’s time was 1:59.85, still the second-best ever.

After a fortnight dealing with the abscess and the rumorsand the disappointment of the Wood Memorial, the way Secretariat disposed ofhis West Coast rival convinced Turcotte that the toughest challenge was behindhim. He said as much to Laurin and Chenery.

“I said it’s downhill from here on, because he came backgood, and he looked fit and ready to run,” Turcotte said. “I knew that he had alot of speed, and I could use him whenever I wanted.”

That led Turcotte to do something different May 19 in the 1973Preakness. For only the second time in his 14 races to that point in his career,Secretariat was taken forward early.

“Remember the Preakness, where I made that bold move around thefirst turn?” Turcotte asked before recounting a since-disproven myth aboutPimlico. “They were afraid about the turns. I said, ‘Don’t worry about theturns. They’re the same as Kentucky.’ When I went to drop in, the other horseswere trying to slow down the pace, so I just let him run by every horse aroundthe first turn. When I hit the back side, I actually delayed and controlled therace the rest of the way.”

Secretariat, who was the 3-10 favorite, and Sham, the 3-1second choice, finished one-two again. And again the margin was 2 1/2 lengths. Thanksto a clocking mistake that day, it would take 39 years and a dose of updatedtechnology for the Maryland Racing Commission to rule the winning time was1:53.0, still a record. Sham’s time of 1:53.45 still would be faster than thatof all but five Preakness winners.

He knew how fast

The images of Secretariat’s Belmont Stakes victory weretattooed in the memories of any racing fan who watched it unfold June 9, 1973.The perfectly long stride that never changed. The ever-lengthening lead thattested the limits of the CBS TV cameras. The head-shaking fractions that suggestedinsanity before they confirmed greatness.

The three weeks before that indelible tour de force were freneticallyendless, what with TV and radio coverage everywhere and cover photos on SportsIllustrated and Time and Newsweek, media affirmations thatseem so anachronistic now.

The pressure was intense. These 50 years later Turcotte soundedlike the quintessence of calm, because Secretariat looked so good in morningtraining. If Turcotte had his way, Big Red might have taken on one more race beforethe Belmont.

“I was hoping (Laurin) would run him in the Jersey Derby,”Turcotte said, “but when I mentioned that, Lucien said, ‘Don’t mention that again.’ ”

The Jersey Derby was sandwiched nine days after the Preaknessand 12 days before the Belmont. Knightly Dawn, who had tangled with Sham inCalifornia, won the race in the slop at Garden State Park. It was a differentera when it was not such a big deal to run horses back that quickly, but Laurinwas not biting.

“I told him that (Secretariat) was going to work faster thanthe Jersey Derby would be run,” Turcotte said. “As it turned out he was workingfaster than the horses running in the afternoon, so I was very, very confidentthat he was going to win the Belmont.”

Onlookers thought Secretariat appeared calm before the 1 1/2-miletest of the champion. Maybe too calm. Turcotte said that might have been a caseof the horse feeding off the vibe of the rider.

“Oh, he was good,” he said. “I was just relaxed. When you’rerelaxed on a horse, the horse will be relaxing with you. If you’re nervous, thehorse will get nervous. I wasn’t nervous at all. First of all I knew he was fit,and the distance didn’t matter to us.”

In 50 years Turcotte has been asked thousands of times aboutthat race. Reporters have tried countless ways to try to frame the memorydifferently. This time the question was whether this was the greatest run by ahorse whose jockey was sitting chilly.

“I would believe that. I believe so,” Turcotte said. “I wasgoing to stay second or third, but when we hit the first turn, I’d see theother jocks take a hold of their horses. So I just dropped to the rail and lethim run.”

Sham tried to keep up, but he withered to finish last against the impossible fractionsof 23.6, 46.2, 1:09.8, 1:34.2, 1:59.0 and, finally, the winning time of 2:24.0.And the mind-boggling margin of 31 lengths. Those last two numbers are to racingwhat .406 and 762 are to baseball.

“I knew exactly what I was doing,” Turcotte said. It was ananswer that might as well be his mantra. “My horse was running beautifully,very relaxed. He was long-striding. He was so easy. He was breathing beautifullyunder me. I had no worries at all in the Belmont.”

Legendary photographer Bob Coglianese captured a famousimage from his infield camera of Turcotte looking to his left at the clock onthe toteboard to forever gauge Secretariat’s greatness. Turcotte has told thatstory time and again.

Less well-known is what happened about a minute after aquarter-century of the sport’s Triple Crown frustration had been wiped away infront of 69,138 fans at Belmont Park and 15 million people watching on TV. Amidthe gleeful maelstrom, it was a conversation between two men down by theclubhouse turn.

“The outrider pulled up alongside me,” Turcotte said. “He says,‘Do you know how fast you were running?’ I said, ‘Yeah, 2:24 flat.’ He says, ‘What?’I said, ‘2:24 flat.’ He says, ‘Unbelievable.’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Yeah,you got that right. How did you know?’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve got a clock in myhead.’ I was kidding. Then I told him that I sort of watched the clock stop onthe infield board.”

Count that as the first of thousands of stories Turcotte wasasked to tell after Secretariat made history worth celebrating all over again50 years later.

Still building a legacy

Turcotte’s time nowadays is focused on his four daughtersand five grandchildren and his beloved Gaetane, to whom he has been married forgoing on 58 years.

“She doesn’t feel that great,” Turcotte said, “but we’remanaging. The kids are coming around now. The kids come in and help.”

The ups and downs have been many since 1973. Turcotte’scareer ended in the summer of 1978, when he was paralyzed in a fall at BelmontPark. He was hurt again in 2015 in a snowy accident driving near his home inNew Brunswick.

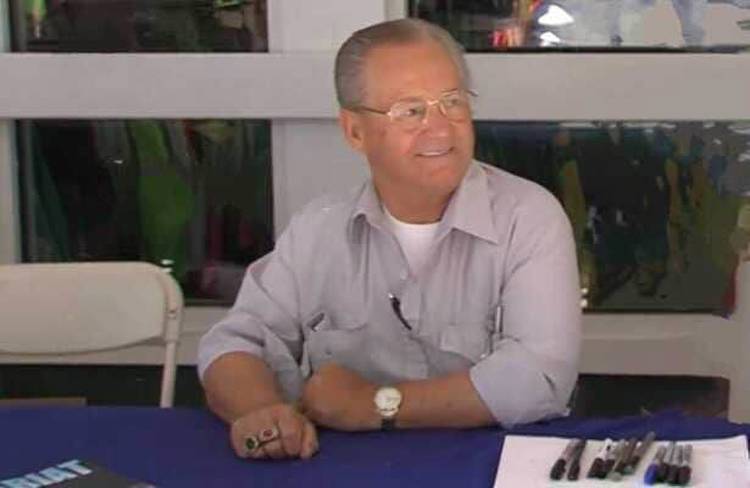

But he is not just a survivor. Turcotte has spent a lot ofyears staying in public view. He has made appearances to sign autographs, meetfans and reminisce about Secretariat. Those meet-and-greets have gone a longway toward raising money and awareness for the Permanently Disabled JockeysFund.

In his hometown, there are very visible reminders of Turcotte’sHall of Fame career.

“In Grand Falls here, first they named a bridge after me,”he said, referring to a span built in 1976 that crosses the Saint John River. “Thenthey put up a statue, a monument to finishing the Belmont and winning by 31lengths.”

There are at least six Secretariat statues across NorthAmerica, the newest of which is on a Triple Crown tour this year before it is placedthis summer on its permanent pedestal in Virginia. There is also a locallyfamous mural of Turcotte and Big Red on the side of a brick building indowntown Lexington, Ky.

For anyone who is, say, 60 or older, they are reminders of afive-week snapshot that has faded only slightly from its vivid, original tones.For everyone else who is younger, the statues and mural and bridge and ongoingtributes may bring to life a story that stands out from so many dusty fragmentsof history.

Turcotte’s grandchildren are aware of his legacy. Not somuch through the monuments, he said, but with modern technology.

“They’re all on the phone now and YouTube,” Turcotte said. “Theyknow a lot. They’re proud of their grandpa, yeah.”