A techy, hip and bold new idea is revolutionizing horse racing

They celebrated on the Churchill Downs rails and in the grandstand, at homes across America in front of their living room televisions, in garages turned makeshift party rooms, and standing in front of corner TVs as the sun spilled in from the sliding glass doors. Ordinary people and wealthy ones, old and young, some sipping cocktails, others swigging beers, all wearing either baseball hats or buttons pledging their loyalty to Mage as he crossed the finish line first at the Kentucky Derby.

In 1605, King James I — he of the eponymous Bible who, contrary to biblical piousness, was known to place a wager — discovered a perfect place to perch a grandstand and brought his horses there to run around a track, ostensibly birthing horse racing. It has been the sport of kings, more or less, ever since. Horses don’t come cheap, at least not good ones, and an owner’s worth generally runs somewhere between generationally wealthy or just obscenely so. Everyman and Everywoman tend to get no closer than the bettor’s window.

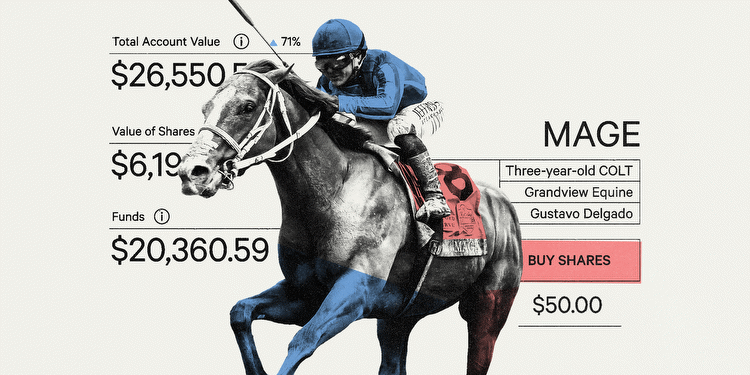

Yet when Mage loads into the starting gates for Saturday’s Preakness, in search of the second leg of the Triple Crown, he will take with him 391 owners as disparate as their Derby celebrations. Some in for a lot; most in for a little. They represent Commonwealth, a sports investment app that more accurately should be called Common(ers) Wealth, considering its Everyman appeal.

The concept is simple: Buy a share in a racehorse — for as little as $50 — and then, if all goes well, earn a cut of its winnings. The effect on horse racing could be downright revolutionary. Forty-one tracks have closed since 2000; two years ago, Arlington, outside of Chicago, shuttered after more than 100 years in existence. Some of the remaining tracks have been saved and salvaged by casinos, existing in, at best, an uncomfortable relationship. Most casino owners don’t necessarily want to run racetracks. The sport is in desperate search of both new fans and relevance outside of its three Triple Crown Saturdays. Despite all the folks who love a good Derby party, not many come back to the track.

Commonwealth may not solve the riddle entirely, but it definitely can help.

Since Mage’s Derby win, 8,000 people have signed up for the app. That’s 400 more than went back to Churchill last Thursday, on the first day of live racing after the Kentucky Derby. “Honestly, in my opinion, this is the biggest way possible to grow the sport,’’ says Preston Troutt, whose horse racing roots run deep via his family’s storied WinStar Farms, and who has led the traditional farm into an unorthodox partnership with Commonwealth. “You don’t need to know a single thing about horse racing. You don’t have to grow up in the industry. If you’re willing to put in $50 and risk losing it, you’re in with an experience that’s unlike any other out there.’’

Brian Doxtator grew up in Richland, Mich., went to Western Michigan and majored in finance. His initial horse racing knowledge began and ended with a few trips to Pimlico while working in mergers and acquisitions in Baltimore. Each year he’d join a bunch of analysts at the Preakness, where from their box seats they’d watch the winners cross the finish line and the muddied and bloodied dissolute emerge from the infield.

He enjoyed the mayhem, and appreciated the horses, even if he didn’t necessarily understand it all. As his career veered toward more entrepreneurial endeavors and subsequent relocations to New York, San Francisco and eventually Los Angeles, he’d always find time to visit the track for some fun. After helping grow Playhaven (now Upsight), a marketing platform for mobile app users, and launching a bridal business, LOHO Bride, with his wife, Christy, Doxtator was living in L.A., searching for his next business venture.

A classic car hobbyist, he went to a car show in 2018, happening by a tent sponsored by Rally Road. The company was offering a share in a Lamborghini, and intrigued — by the business model, if not so much the offer of the share — Doxtator started peppering the people with questions. By the time he left, he was curious enough to go directly to his home office and download 300 pages of dry, eye-glazing SEC filings, curious to better understand the nature of the business. Rally Road was, essentially, offering ordinary people to enjoy the extraordinary — things such as art, rare books and cars that were otherwise outside of their budgets.

Doxtator loved the idea but saw two problems. For one, there was no definitive payout; only if the items were sold would shareholders make any money. “And there was no moment,’’ Doxtator says now. “There’s no journey. You invest in a car and then what? There’s nothing happening, no reason to interact with the consumer.” But he liked the concept enough to put his mind to it, and started thinking about ways to make it more experiential, considering the two most popular American experiences — music and sports. Christy, however, was pregnant with their first child and Doxtator thought chasing the rocker lifestyle might be a tough sell. But sports?

Americans spend, on average, $55 billion to attend sporting events each year, drawn by the spectacle but also enticed by the allure of winning. For most people, their interest is rooted in allegiance — to school, to hometown, to athlete — with very few crossing into any sort of proprietary relationship to their team or player. Doxtator imagined how he could tweak the Lamborghini share model to athletics, giving people not just a team or an athlete to root for, but a legitimate piece of the pie. Like the publicly owned Green Bay Packers but an even deeper connection, where shareholders would be extended unique privileges.

Team sports, he knew, would be complicated; they aren’t governed by prize money. He needed a hook. Which is how, on a random weekend visit to Santa Anita racetrack, Brian Doxtator, financier-turned-start-up-wiz, began to see himself as a horseman. “There’s a moment. There’s winning and it’s something that the average person usually can’t get in on,’’ he says. “This was it.’’

Only problem — Doxtator’s complete lack of horse racing knowledge. And then he opened his Instagram.

Chase Chamberlin isn’t entirely sure why he loves horses. Maybe it skipped a generation, he thinks, and landed on him. His dad’s dad liked them and rode a bit (at 89, he’s Commonwealth’s oldest investor). From what the family knows, his mom’s dad did, too. He grew up going to Will Rogers ranch in California but he died at 21, not long after Chamberlin’s mom was born. “We just figured he liked horses,’’ Chamberlin says. Whether it was genetics or not, Chamberlin declared his desire to ride at the age of 4, and his indulgent mother agreed to let him start lessons.

By the time he reached high school, Chamberlin had cast aside traditional athletic pursuits to concentrate entirely on his equine passion. He rode horses, showed them, trained them, even helped with horse therapy. “It wasn’t the Kentucky story where I was born into it,’’ the Michigan native says. “But somehow it got into my bloodstream.’’

After a lifetime involved in horses, Chamberlin was finally persuaded by a buddy to go all in. He spent $5,000 on a mare in a claiming race. Thrilled with his purchase, Chamberlin posted a picture of Scat Lady on his Instagram.

That was in June 2018 — coincidentally around the same time Doxtator went to Santa Anita and started searching for a horse partner. Though Chamberlin is eight years younger, the two grew up in Richland, a rural Michigan town outside of Kalamazoo. Doxtator went to high school with Chamberlin’s older sister.

By the time Doxtator spied his Instagram post, Chamberlin had steered out of traditional business and into startups and entrepreneurial endeavors. In 2018, he was working as a video strategist in a job he loved, and knew he was good at.

Before he finished reading Doxtator’s proposition, Chamberlin was ready to shuck his job and go all in. Not only did it present him a chance to work full time in horses, but also he was certain it would work. “Except he didn’t get back to me for a couple of days, and I gotta be honest, it was like I found the love of my life and she ghosted me,’’ Chamberlin says. “In my head, I was already a year down the road with this. I was so nervous that he wasn’t serious about it.’’

Doxtator was, of course. He was just busy. Eventually he got back to Chamberlin, the two agreeing to partner. They spent months on the phone hammering out the details of their venture — Chamberlin usually pacing in and out of his house to calm his nerves. Along with the business plan, they worked on the app, recognizing that if they wanted to target a younger audience, they needed it to be user friendly and mobile-ready. The pandemic delayed their launch but turned out to be a blessing, allowing them more time to fine-tune the critical details and get all of their SEC paperwork in order.

The SEC, however, also required an actual horse to qualify and launch the business. In late 2020 the pair spent $20,000 on a horse named Biko (they named him after the Peter Gabriel song) and put him up on their nascent app for offer, mostly to friends and family since the business wasn’t entirely launched just yet. The shares sold out.

Except, while this was Commonwealth’s business model come to life, the pair wasn’t sure Biko was exactly the sort of horse they envisioned. They imagined investors enjoying the thrill of a moment — a big moment — with horses competing in marquee stakes races, not random weekday claiming races. “It’s not quite the same on a Wednesday afternoon,’’ Doxtator says.

They didn’t think Biko necessarily had it in him, and wound up refunding everyone who had invested in the horse in full (they weren’t wrong; Biko has won $33,000 in his career and has yet to run a stakes race). But horses cost money — to buy, to feed, to train — and by themselves, they weren’t equipped financially to be in the sort of races they wanted to race in. “It is the sport of kings, remember,’’ Chamberlin says. Doxtator and Chamberlin needed a partnership.

Armed with their techy, hip and bold new idea to transform horse racing ownership, they went to the very staid, decidedly unhip farms of Kentucky, where even the manure smells of old money. “I’m flying from Los Angeles to Kentucky to pitch a tech startup to a breeding farm, ‘’ Doxtator says. “More than a few told us to hit the road.’’ One farm — and more to the point, one person — was intrigued.

Preston Troutt was in elementary school when his parents bought a 400-acre horse farm in Versailles, Ky. Today WinStar farms stretches across 2,400 acres, houses 20 stallions and counts one Triple Crown winner — Justify — among its racing team “alumni.” It looks like it’s cut out of a horse farm storybook, replete with rolling hills of bluegrass and emblemed gates opening onto the property.

But Kenny Troutt, Preston’s father, is — by horse racing standards, at least — new money. He made his fortune via Excel Communications, combining marketing and networking strategies with the burgeoning telecommunications industry. Within eight years, Excel sales topped $1 billion, and in 1998 Kenny Troutt sold the company for $3.5 billion. He used the money to start WinStar, funding a long-held passion (Kenny saw Secretariat win the Derby as a college student) with his own 1980s version of a startup.

The 28-year-old Preston saw in Commonwealth the same sort of bold thinking his father used to launch his career. For years, Preston brought friends to the track. Invariably, they bet on some races, took some pictures and, unless he invited them again, rarely found their way back. Along with ownership, Commonwealth’s plan included interviews and info direct from the trainers, a chance for shareholders to watch workouts, visit the paddock and even, space willing, to celebrate in the winner’s circle. Moreover the attachment didn’t end after two minutes of a race, as a bet does. It extended for as long as the horse raced and even through breeding, so long as his or her rights weren’t sold. Essentially Commonwealth was giving ordinary folks a chance to have every horse owner’s rights, save voting privileges.

Preston, a Penn grad with his own eye for new business, loved the concept. He loved even more what it could do for a sport he believed in. “I always thought once you get people really involved in the sport, they’d love it,’’ he says. “But that’s kind of hard to do. This is a lottery ticket with an experience attached, and you only need fifty bucks.’’

After a year of working out the details, Commonwealth and WinStar announced their partnership in April 2021. Though Chamberlin is heavily involved in the selection of Commonwealth’s horses, WinStar provides assistance, and also offers some of its foals to the endeavor. The first horse (aside from the dismissed Biko) they offered was a colt named Country Grammer. They sold 2,277 shares for a total of $113,850 in fewer than 90 minutes. “By the time we got Country Grammer, I had $128 in my bank account,’’ Chamberlin says. “Brian and I had busted our butts, and had gone all in. We just went for broke.’’ Fewer than two days after they bought the horse, he injured his ankle. As they did with Biko, Doxtator and Chamberlin offered refunds. Only this time, hardly anyone took them.

Eight months later — in March 2022 — Country Grammer won the Dubai World Cup and has since won $14.5 million. Of that $14.5 million, $1.5 million has been dispersed among the 2,277 shareholders. “I used to say things were surreal,’’ Chamberlin says. “I didn’t understand the meaning of the word until we were standing there holding the trophy in Dubai.’’

As a first grader on the recess yard, while the rest of his schoolmates competed in normal foot races, Chamberlin would convince his pals to play Kentucky Derby. He’d assign them each a horse name. He’d give himself the fastest, and then try to live up to the hype.

Doxtator and Chamberlin liked Mage’s chances in the Kentucky Derby. He didn’t race as a 2-year-old and had only raced three times in his 3-year-old campaign, but he also lost by just a length to Derby favorite Forte (who was eventually scratched) in the Florida Derby.

They knew the whole thing was already too fairy tale — to even have a Derby entrant this early in their venture is preposterous — but they headed to Louisville, Mage hats plopped on their heads, feeling fairly bullish.

Mage got a lousy break out of the starting gate, a bad omen. He’d done the same in his previous two races, and lost. He trailed the pacesetters early and struggled to find space to make a move through the second turn. But given a wedge of room, jockey Javier Castellano took advantage and moved him to sixth at the mile marker. “Then he took off like a slingshot,’’ Preston Troutt says. Mage caught and passed Two Phil’s, winning the Derby by a length and setting off a waterfall of celebrations across the country.

For the 391 people who got in on the offer on Mage, the Derby payoff was about $95 per share (the money paid out quickly on the Commonwealth app wallet). The colt is now valued at nearly $5 million, and could swell to as much as $100 million if he wins the Triple Crown.

It is absolute lightning in a bottle for Doxtator and Chamberlin, who aim to grow their business beyond horse racing. Interested investors can currently buy shares in two Korn Ferry golfers, with inside-the-ropes access at their events, and the duo see a future in similar individual (and expensive) sports, such as tennis, and even poker. Down the road they might even take advantage of NIL, offering ambassador positions to college athletes in return for potential post-grad deals.

But in the moment of the Derby win, or even the hours and days since, neither has immediately thought about the cha-ching to their bank accounts. They were too busy celebrating like madmen, while watching videos of their shareholders doing the same.

Make no mistake. This is a business. They want to make money. That is not all they are after. “Everything is always so warped by the economics,’’ Doxtator says. “But me jumping on the rail, people falling over each other as they were celebrating when Mage crossed the finish line, that’s what we wanted. That’s the moment.’’

A winning moment for shareholders, but potentially a monumental one for the sport.

(Illustration: John Bradford / The Athletic; photos: Michael Reaves/ Getty Images)