After 25 years, it's time to admit that a blown call didn't cost Padres Game 1 of the 1998 World Series

After 25 years, let’s settle this once and for all.

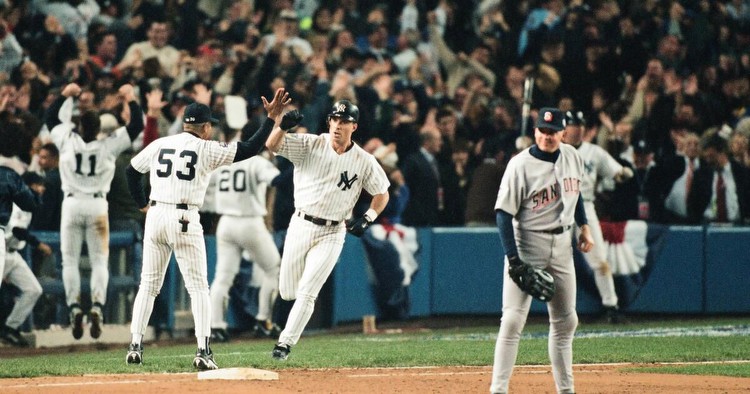

The likely errant call by umpire Rich Garcia on Mark Langston’s two-strike pitch to Tino Martinez isn’t why the Padres lost Game 1 of the World Series to the Yankees a quarter of century ago this month.

One, Langston wasn’t obligated one pitch later to throw the fat one that Martinez ripped for a go-ahead grand slam at Yankee Stadium on the way to a 9-6 win.

Two, the Yankees would’ve remained a slight favorite to win Game 1 even if Garcia made the likely right call instead of deeming the 2-2 pitch too low with two outs in the seventh inning and the score tied, 5-5.

Here’s why: being the home team with a well-rested Mariano Rivera in reserve would’ve advantaged the Yankees, if only slightly.

Sure, Hall of Fame closer Trevor Hoffman gave the Padres a comforting presence. He had closed out the League Championship Series clincher three days earlier in Atlanta. He was prepared to go more than an inning on Oct. 17, 1998 — 25 years ago on Tuesday. Hoffman’s season that year yielded a 1.48 ERA and a baseball-best 53 saves.

Rivera, though, was far more accustomed to getting more than three outs. He had shown he could get up to 10 outs if needed. And he was a monster in the playoffs, pitching to a stunning 0.70 career ERA across 96 postseason outings. Rivera got more than three outs in 58 of those efforts and six to 10 outs in 33 of them.

The closer rivaled Hall of Fame shortstop Derek Jeter as the most important part of a Yankees dynasty that would win each World Series trophy between 1998-2000 to go with its title in ’96.

That’s why, even as Martinez stepped into the box with the score tied 5-5, Baseball-Reference.com’s probability model gave the Yankees a 62 percent chance of winning.

It was a shame that Langston wasn’t rewarded for his seemingly perfect fastball with the count 2-2. As the lefty’s pitch went over the plate’s outer third, seemingly knee-high, Martinez was fooled from the Bronx to Yonkers.

“I was looking for the ball up in the zone,” Martinez would admit.

Langston was unable to overcome Garcia’s call.

The full-count approach arguably called for risking the walk instead of the slam. One Padres veteran said the proper relief mindset was to “not give in” to Martinez. A starter for most his career and in 16 of his 22 outings that season, Langston threw a belt-high fastball over the plate’s inner third. Martinez pulled the 87-mph pitch into the upper deck.

So why did the Padres lose? Go back to events earlier in the seventh inning — if you can bear to relive them all these years later.

Chuck Knoblauch’s three-run home run off Donne Wall, three pitches after manager Bruce Bochy summoned the reliever, dealt the Padres the most harm of any blow. The lofted drive into the left-field seats erased the 5-2 lead with the Padres — who had an 81 percent chance of winning before the home run, per Baseball-Reference — still needing two more outs in the seventh.

Bochy said he chose the reliable reliever over converted starting pitcher Joey Hamilton to replace a worn-out Kevin Brown after the Yankees put runners on first base and second base.

The case for Wall: he delivered a sharp 1998 season as a full-time reliever. His season numbers showed a 2.48 ERA, a very low home run rate (0.8 per nine innings) and a 1.166 WHIP.

The case for Hamilton: he was more apt to get a double-play grounder, threw a much hotter fastball and had thrown 4 2/3 scoreless innings across three relief outings that postseason, in addition to pitching into the seventh of his Game 4 start in the NLCS.

From the outset, Wall was off his game against fellow righty Knoblauch, who’d been having a poor postseason. Wall was outside the strike zone by several inches with both his breaking ball (low and away) and fastball (up and in).

Able to delete Wall’s nasty changeup, plus the curveball, Knoblauch could look for a 2-0 fastball.

When Wall’s 89-mph fastball came in fat, Knoblauch met it flush.

Bochy had been served well by trusting his gut instincts in his four years directing the Padres. In years to come, Bochy heeded his radar en route to two National League West titles with three Padres, three World Series titles with the Giants and the current American League Championship Series with the Rangers.

But in a text Friday, Bochy acknowledged he went against his instincts when he picked Wall over Hamilton.

“My gut was leaning Hamilton,” he said, “but Wall was the guy we had used in that situation the majority of the time. So, I did second-guess myself.”

He added: “Joey was a power sinker-slider guy, which matched up better on Knoblauch.”

Hamilton said he was warmed up and ready to pitch when Bochy walked toward Brown.

“I thought with all my soul that I was going to be the one that was coming into the game in that situation,” Hamilton said Friday by phone. “I would’ve pounded Knoblauch in with a hard sinking fastball, gotten the groundball to the left side and been out of the inning. That’s how I saw it.”

Hamilton praised Wall’s excellent 1998 season, but said relief work suited him, too.

“It was always fun coming out of the bullpen because you didn’t have to worry about going seven innings,” he said. “You could just air it out.”

When a pitcher gears himself up to pitch in the first World Series game of his career — in Yankee Stadium no less — he’s bound to be beside himself when someone else gets the ball. No matter how much he respects that teammate.

“I was not happy when I didn’t go into the game,” Hamilton said. “But then, after the inning, it went from not happy to borderline irate. But, it’s Boch’s decision. I remember I went into the clubhouse after the game and was tearing my locker up a little bit. (Pitching coach) Dave Stewart said, ‘Hey, you know this was my decision. Donne had been doing this job for us all year.’ I was like, ‘OK, whatever.’”

Years later, Hamilton learned directly from his former manager that Bochy had made the decision.

Before the seven-run avalanche, the Padres had appeared capable of swiping Game 1 from the winningest of all Yankees teams.

Slugger Greg Vaughn homered twice off David Wells. As part of his three-hit night that began with a gorgeous hit-and-run single, off a shin-high curveball wide of the far corner, Tony Gwynn hit a two-run homer off an upper-deck beer sign to break a 2-2 tie in the fifth.

In San Diego, fans screamed as Gwynn circled the bases. One particularly excited Padres fan was at Yankee Stadium. Tony Gwynn Jr., the Hall of Famer’s son, stood up in the Padres’ family section and screamed as his dad’s drive soared. Then the younger Gwynn, who had turned 16 earlier that month, let nearby Yankees fans have it. He razzed actors Denzel Washington and Bruce Willis, who’d been teasing him. At that point, Alicia Gwynn told her son to sit down.

Despite illness, Brown — the Padres’ Game 1 starter — got off to a fast start. But when he misfired a 91-mph splitter to Chili Davis with one out in the second inning, the ensuing line drive that stuck Brown’s left shin could be heard in the pressbox.

Despite the ace laboring for the rest of that inning and losing velocity as the game unfolded, the Padres led 5-2 when Brown handed Bochy the ball five innings later.

“Biggest memory,” Bochy said in his recent text, “is having to get Brown with the flu-like symptoms he was dealing with.

“Obviously,” Bochy added, “the missed call (Langston to Martinez) was a game-changer, too.”

The final score was 9-6, and as the Yankees crowd sang along with Frank Sinatra’s “New York, New York,” it felt like the series was over.

All that remained, as it turned out, was for the 114-victory Yankees to roll to a rout in Game 2, overcome pitcher Sterling Hitchcock’s strong outing in Game 3 — the first World Series game in Mission Valley since 1984 — and then survive Brown in in Game 4, whereupon Rivera logged his third save of the series to complete the sweep.

San Diego hasn’t sniffed a World Series since.