Brooks Robinson, legendary Hall of Fame third baseman for the Orioles, dies at 86

He was known, simply, as Brooks — a name that stirs images of a ballplayer sprawled in the dirt, glove arm raised in triumph to show an impossible catch.

Hall of Fame third baseman Brooks Robinson died Tuesday. The Owings Mills resident was 86.

“An integral part of our Orioles Family since 1955, [Robinson] will continue to leave a lasting impact on our club, our community, and the sport of baseball,” read a joint statement released by his family and the Orioles. “He played the game with a childlike spirit [and] ... third basemen from all levels of the game will forever look to Brooks for inspiration.”

Through much of baseball’s golden age, Brooks Calbert Robinson Jr. was a poster boy for the national pastime, a symbol of Americana whose visage was even captured in a 1971 Norman Rockwell painting.

The face of the Orioles for nearly a quarter of a century, Robinson won the heart of the city that adopted the deft-handed kid from Arkansas in 1955 and never let go. Before Ripken, there was Robinson. Before Cal, there was Brooks. Before the Iron Man, there was the Human Vacuum Cleaner. As Oriole icons, no others come close.

“He was the heart and soul of the Baltimore Orioles. Always has been. Probably always will,” said former Orioles catcher Rick Dempsey, who joined the team in 1976. “You understood why the Orioles became a powerhouse, because Brooks Robinson just paved the way, the way he played. Everybody else fell in line behind him.”

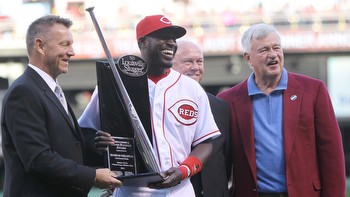

Robinson played 23 years in Baltimore, piling up numbers that made him one of the game’s greatest third basemen and which put him in the Hall of Fame in 1983. He was the American League’s Most Valuable Player in 1964 and the World Series MVP in 1970, when he led the Orioles over the Cincinnati Reds. Then a balding, 33-year-old father of four, Robinson thwarted the Big Red Machine, game after game, on a national stage with brilliant backhand stabs, off-balance pegs and timely (.429) hitting.

From then on, America knew his name.

“I’d pay to watch him play,” Reds star Pete Rose marveled.

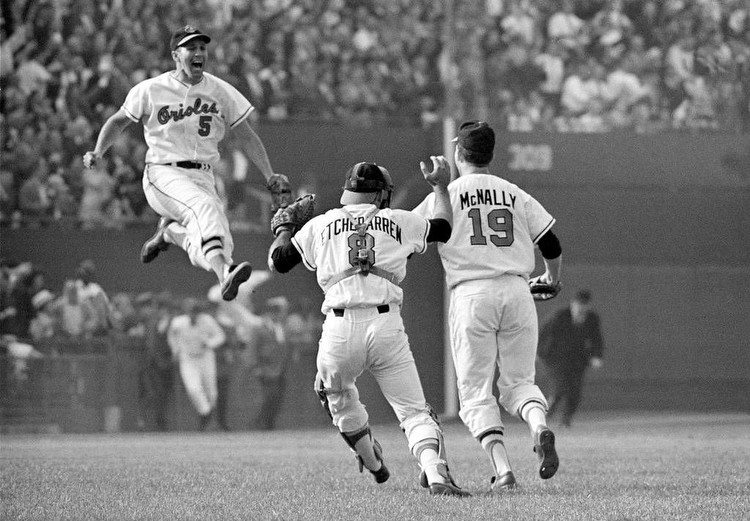

Four years earlier, Robinson had helped the Orioles win their first world championship. In 1966, they swept the Los Angeles Dodgers in four straight games as Robinson homered in his first at-bat. Fans remember his joyful leap in the air, captured on film, at the Series’ end.

"My kids thought it was trick photography," Robinson said. "They told me, ‘Dad, you never jumped that high in your life.’ "

Robinson hit 268 home runs, played in 18 straight All-Star games, won 16 consecutive Gold Gloves and set a slew of records for third basemen, including most putouts, assists, double plays and fielding percentage (.971). Even Pie Traynor, the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Hall of Fame third baseman of the 1920s, paid homage to Robinson some 40 years later.

"I once thought of giving him some tips, but dropped the idea," Traynor said. "He’s just the best there is."

In 1999, Robinson was named to Major League Baseball’s All-Century team. In 2007, baseball fans named him the best defensive third baseman of all time in balloting conducted by Rawlings. No other position player received as much of the vote (61%).

“Brooks stood among the greatest defensive players who have ever lived,” Commissioner of Baseball Rob Manfred said in a Tuesday statement, citing his record and calling him “a true gentleman who represented our game extraordinarily well on and off the field all his life.”

Modest to a fault, Robinson seemed unfazed by accolades. Accepting his MVP award in 1964, he quipped, “I’m still trying to figure out how I hit 28 homers.”

In 1983, at his Hall of Fame induction, Robinson appeared out of place, Sun columnist Michael Olesker wrote:

"Brooks walked onto the stand looking shy and a little self-conscious, as though maybe a mistake had been made, that he’d gotten in on a pass somehow but was thrilled about it anyway."

To the end, Robinson seemed perplexed by his inclusion at Cooperstown.

“Every month, I think about going back there to make sure no one takes my plaque off the wall,” he told The Sun in 2007. "There’s [Ted] Williams, with a lifetime batting mark of .344. And Joe DiMaggio. And [Stan] Musial.

"And, oh, there's Brooks, who hit .267.

"How did I get into the Hall of Fame, anyway?"

Pigeon-toed and slow afoot, Robinson made up for it with sure hands, lightning reflexes and an unerring knack for making acrobatic throws that would nip runners by a whisker. He barehanded bunts with poetic precision.

"The baseball didn’t have much of a chance, going one-on-one with Robinson, be it on the ground or in the air," wrote Phil Jackman, who covered the Orioles for The Evening Sun.

Hitting was another matter. A notorious streak hitter, Robinson carried the club (.295, 17 home runs) for the first half of 1966, and then tailed off at the end (.236, 6 homers). But his fielding never wavered.

"Watching Brooks play third is like watching Oscar Robertson play basketball every day," teammate Frank Robinson said.

Robinson’s fame was such that he shared his moniker with a host of children who were named for him, including former pro quarterback Brooks Bollinger (Dallas Cowboys) and punter Brooks Barnard (Maryland and New England Patriots).

“There must be hundreds of little Brookses running around,” Robinson said in 2000. “I’ve even had a few dogs named after me.”

Also a road in Pikesville (Brooks Robinson Drive) and a plaza outside the ballpark in York, Pennsylvania, where his baseball career began.

It was there, in 1955, one year after the birth of the modern Orioles, that “Bob” Robinson (as the York stadium announcer called him), a free agent from Little Rock, launched a 23-year career that endeared him to Baltimore and to baseball.

“Brooksie was just the best person you’d ever want to meet on a baseball field, the best person God ever put on a baseball field,” said Dempsey, who left the Orioles in 1987 but returned to play his final season with Baltimore in 1992.

Robinson was 18, a skinny, moon-faced kid, when he signed with the Orioles for $4,000 on May 28. The son of a fireman, he’d had a paper route where he practiced throwing dailies onto the porch of Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, the New York Yankees catcher, who lived nearby. Robinson’s high school (Little Rock Central) had no baseball team, so he starred instead in track and basketball and, in summer, played infield for the local American Legion club.

Courted by 13 of the 16 big league teams, he chose Baltimore because he thought the lowly Birds offered him the quickest ride to the majors.

Assigned to York (Class B), Robinson played second base but soon moved to third because of his quick reflexes and lack of range. Recalled by the Orioles toward the end of 1955, he got two hits in his first game on Sept. 17 against the Washington Senators, and thought he was hot stuff.

“I believed this game was made for me,” Robinson recalled. “I got cocky as the devil. What a mistake! I went 0-for-18 the rest of the year, and struck out 10 times.”

He couldn’t hit a curve or changeup, and appeared jittery at third.

"I played like I was on roller skates," Robinson said.

The Orioles liked what they saw.

“One of these days, that kid is going to be the best third baseman in the league,” manager Paul Richards predicted.

Robinson spent much of the next two years in San Antonio (AA), honing his skills and wowing the club with his fielding, however offbeat it appeared.

“We called him ‘Crazy Legs’ in the Texas League,” Oriole outfielder Carl Powis once said. “He looked like [football star] ‘Crazy Legs’ Hirsch the way he chased in on grounders. But he gobbled up everything.”

Robinson bounced between the minors and the big leagues for five seasons, struggling at the plate before making it for good. Before that, the Orioles had tried as many as 10 players a year at third base. By 1960, the job belonged to one man. His it would stay for 16 years.

Everything dovetailed for Robinson in 1960. Only 23 years old, he hit .294, set a club record for hits and led all AL third basemen in fielding. He made the All-Star team, won his first Gold Glove, finished third in balloting for MVP and nearly led the Orioles, a sixth-place team the year before, to their first pennant.

“He’s the most improved player in the league,” New York Yankees manager Casey Stengel said.

That fall, Robinson wed Connie Butcher, an airline stewardess he’d met on a team flight to Boston. They were married for 62 years. She survives him, as do four children — Diana Farley, Brooks David, Christopher and Michael Robinson, 10 grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

“His historic career on the field pales to the impact he’s made on so many of us. The memories we all share of Brooks will live on,” fellow Orioles legend Cal Ripken Jr. said in a Tuesday statement.

From the start, Robinson spoiled Orioles fans who were convinced of his infallibility with the glove.

On those rare occasions when Robinson erred, Evening Sun columnist Bill Tanton wrote in 1963, “It’s like [Arthur] Rubinstein hitting a sour note, or one of the Flying Wallendas toppling from the high wire.”

Businesses liked his crew-cut looks and Southern drawl and lined up to bandy about his name. By 1964 he owned a sporting goods store, had part ownership of the Gorsuch House Restaurant, and was churning out radio commercials for everything from banks to margarine to spaghetti. Vitalis hired Robinson to hawk its hair tonic, ignoring that he was half-bald.

That year, 1964, was his best in baseball. He had career highs in average (.317), homers (28) and RBIs (118), which led the AL and iced his MVP award. Again, Robinson almost single-handedly led Baltimore to a flag. The Orioles finished two games out.

That winter, the Orioles signed him for an unprecedented $50,000. If this went to Robinson’s head, he didn’t show it. In January 1965, when a blizzard made roads impassable, he instead took a train to Cumberland for a speaking engagement, traveling 5½ hours each way.

“He never bragged about himself or anything. He just went out and did his job. You had to watch him. His approach to the game is what the game should be today,” Dempsey said.

“Brooks was a genuine person. There was no acting or trying to play a role. We were just lucky that we all had him in our lives,” former Orioles pitcher Jim Palmer said, with tears in his eyes, during Tuesday’s game against the Washington Nationals.

Nor did Robinson mind sharing the limelight in 1966, when the Orioles dealt for Cincinnati slugger Frank Robinson. The trade clinched Baltimore’s first pennant as the pair combined for 72 homers and 222 RBIs and were dubbed the “Swish Family Robinson.”— MLB Network (@MLBNetwork) September 26, 2023