Chris Robshaw exclusive: World Cup back-rows and their responsibilities

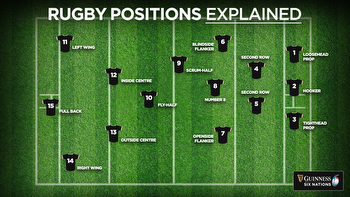

Former England captain Chris Robshaw highlights the different back-row systems being implemented at the Rugby World Cup.

Have you wondered whether Charles Ollivon is actually an openside flanker and why Pieter-Steph du Toit wears number seven but is actually a blindside?

Well, Planet Rugby writer James While sat down with Robshaw to get the former Test flanker’s views and insights on the current back-rowers on display at the World Cup.

He explains the balancing act teams employ in their selections as well as the blindside/openside and the left/right flanker system.

Skill blend

“As a former flanker who was happy playing either six or seven, or open or blindside, I take a huge interest in how the various teams in the World Cup are configuring their back-rows, often to the point that some of the commentators and analysts are getting quite confused, so I wanted to explain the various systems,” he told Planet Rugby.

“As we enter some massive matches this weekend, it’s interesting how the top teams all have slightly different configurations of their loose trio.

“If you go back to James Haskell and I playing together for England in 2016-18, neither of us was an out-and-out openside in the British sense of the position, so rather tongue in cheek, we coined the phrase ‘6 and a half’ and even got our shirts printed up for one of the press conferences of that era, although Hask played on the openside and me on the blindside during that period.

“But the key thing was between us and Billy Vunipola; we had a blend of skills that allowed Eddie Jones‘ game-plan to flourish. I was the key jumper of the three and also owned the role of clearing and contesting at rucks (although all three of us performed the duty), while Billy was the carrier and Hask was the disruptor in the face of the 10 and 12.”

He added: “It’s that skill blend that’s far more important than being confined in your positional thinking. You need a lineout specialist, a carrier, and a fetcher, and each man needs to be dynamite at ruck and breakdown time with a flawless tackle completion. No big ask, eh?! That’s why the sides with dominant back-rows are winning the Tests.”

Left and right or open and blind?

“European and South American sides tend to play left flank and right flank over open and blind, as evidenced by Argentina, France and Italy,” Robshaw explained.

“So, as a simple example, when France take the pitch, there is no openside and blindside; you have Francois Cros (6) on the left flank and Charles Ollivon (7) on the right flank all match, and they stay like that.

“In the traditional British or New Zealand system, the flankers will swap sides at each scrum so that the openside is covering the wider side of the pitch and the blindside the narrower side.

“In France’s case, Cros playing on the left needs to be their tackle machine; you have one less defending player (your scrum-half) on that left channel all match, so speed off the side is crucial, and Cros controls a lot of the French defensive effort around that pressure moment and contact point.

“In open play, he’ll defend the sides of the ruck with the faster Ollivon in the 12/13 channels, taking the second wave of attack. If you were to categorise them in British terms, you’d say Cros is their openside and Ollivon more suited to blindside, the opposite of their shirt numbers.”

The former England skipper added: “Argentina are similar, also playing exclusively left and right, not open and blind; Marcos Kremer (7) is that massive unit, whereas Pablo Matera (6) is the jackal man, closing off the sides of the ruck. It’s same for Italy, Uruguay and some of the other teams.

“Of course, if you weren’t confused enough by now, the Springboks number their flanks the other way around, BUT play open and blind, just to be contrary!

“Siya Kolisi is really their seven, scrummaging on the open, and Pieter-Steph du Toit is their blindside, wearing seven but acting as a blindside. It’s just a tradition over there, and they’ve pretty much always numbered like this, going back to Reuben Kruger (open-6) and Andre Venter (blind-7) in the 90s.”

Which is better?

“The key question, of course, is which system, left and right or open and blind, works better? There really isn’t a binary answer to this, and it really depends on which you’ve been brought up learning,” Robshaw pondered.

“Some coaches, especially in France, might argue that the left and right system gives a better connection between the flankers and props as you have the same unit doing the same job at each scrum (in the same way locks tend to prefer one side or the other) and I’d probably agree there’s some truth in that, but the downside is that having the flyer on the open all the time can put more pressure on the 10/12 channel off the set-piece.

“For me personally, I was easy on which side I played or which configuration I played, being equally at home on either flank or in either role. I was probably more suited to blindside at Test level, where I won most of my caps, but provided we had the right blend of skills in our back-row unit, I was happy anywhere.”

Match within a match

He continued: “I think the back-row performances have been one of the features of this World Cup. I could, of course, discuss the Irish, Springbok and French back-rows – they’re all absolutely world-class – but two that have caught my eye have been Fiji and Uruguay.

“Fiji have a real balance playing the traditional open/blind configuration. Bill Mata (8) is magnificent with the ball in hand and their key carrier. Levani Botia (7) is arguably the best fetcher in world rugby at the moment, and Lekima Tagitagivalu (6) is a specialist lineout forward with a good general skill set, with the huge Albert Tuisue able to come on and add impetus at eight or blindside.

“Uruguay favours left and right flankers over open and blind, but their team’s performances have largely been built upon the brilliance of their trio. Manuel Diana (8) is that big leggy carrier, brilliant at getting over the gain line. Santiago Civetta (7) is the allrounder with line out and support ability, whilst at 6 or left flank, Manuel Ardao has been absolutely brilliant, snaring six turnovers in his two outings, giving France the scare of their lives.

“I’ve deliberately chosen two emerging nations to illustrate how the two systems work there and how effective either can be, as long as the key core rugby skills are all there.”

Dream team

He concluded: “Of course, no article like this could be complete without my dream trio from the tournament so far, and if I were coaching the World XV against Saturn tomorrow, I’d pick an open and blind configuration with these three men:

6) Charles Ollivon (France): In my opinion, the most complete forward in the world right now, a huge threat with the ball in hand, boasting a Test try every two and a half games and, at 6’7″, a lineout supremo who took three steals off the All Blacks in the opener.

7) Levani Botia (Fiji): I am convinced the man is made from rubber, as his ability to get into the smallest of gaps in the ruck is his superpower. He is a true athlete and good enough with ball in hand to play elite rugby at 12.

8) Caelan Doris (Ireland): Doris’ superpower is his footwork. His ability to carry but get through the tackle with smart running via his stepping is wonderful, and he has the hands to execute brilliant offloads. He gets Ireland through the primary defence and into scramble so many times, and it’s often his initial work from the first carry that is rewarded four or five phases later.

“I really hope that this has helped with the understanding of the various back-row systems; I’ve always believed that the loose forwards win the match and the backs decide by how many. But then again, I might be a little biased!”