Florida Atlantic Was Built for This Final Four Run

There’s a difference between the celebratory joy of a fan whose team has won the game they’d always dreamed about, and the disbelieving ecstasy of a fan whose team won a game they had never even considered winning. The Florida Atlantic faithful who saw their Owls clinch a Final Four berth at Madison Square Garden last weekend were clearly experiencing the latter. Even among the boosters and VIPs who got on the court for the trophy ceremony, the defining vibe was less “YES!!!” and more “WHAT???”

As the players cut down the nets following their 79-76 win over Kansas State, FAU athletic director Brian White joked that he would’ve cut off a pinky finger for a preseason guarantee of an NCAA tournament bid. When asked what he’d cut off for a national title, he declined to answer: “I don’t want to commit right now, I’m in the moment and I’m pretty excited.” I think he was about to offer an arm or a leg before remembering he was dealing with a team that has shattered everybody’s best-case scenarios over and over again. Any body-part-for-a-natty promise could have left him on a Houston operating table next week.

Fans of most professional sports teams enter each season with roughly the same dream: To win a championship. That’s at least somewhat probable in most cases, as those leagues have 32 teams or less. (As a Jets fan, I’d settle for a playoff berth, but you get the gist.) But Division I basketball has 363 teams—too many for everybody to chase the same fantasy. Before 2023, FAU had been to the NCAA tournament only once, 21 years ago. The Owls had a combined postseason record of 0-4—one loss each in the NCAAs, the NIT, the CBI, and the now-defunct CIT. The school had produced zero NBA players. And when head coach Dusty May first saw FAU’s high school–level arena after signing his contract in 2018, he went back to his hotel and told his wife “I just committed career suicide.” After all, five of FAU’s previous seven head coaches never got another Division I job after their stints with the Owls. How could anyone have expected this?

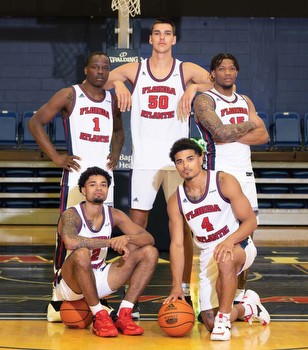

But FAU’s players and coaches were relatively calm after the win. I watched sophomore guard Johnell Davis quietly tie a piece of net to the adjustable strap on his Final Four hat and ensure that a student manager got a picture with the East regional trophy—the practiced moves of a vet who had been here before, even though FAU certainly hadn’t. The Owls seemed surprised when people like me came up and asked whether they’d believed all along they had a Final Four run in them. And on the locker room whiteboard, scrawled in dry-erase marker next to a handful of play designs, was a phrase showing what FAU’s players and coaches thought they were capable of: WE ARE BUILT FOR THIS MOMENT.

“You don’t just show up and win this game,” said May. “They prepared and built and built and built to be here and it was just a result of all of that cumulative effort and hours.”

While the rest of the college basketball world spent January and February hyping up teams which wouldn’t reach the Elite Eight, FAU was completely dominating Conference USA. The Owls went 31-3 before the start of the NCAA tournament, tied for the fewest losses of any team before the brackets were released. At one point, they’d won 20 games in a row, 13 by double digits. That win streak started in November with a victory over Florida, arguably the biggest win in program history—but May urged the team not to treat it like that. “This can’t be the pinnacle of our season,” May said at the time. “Hopefully this is just one of those moments and not the moment.” He said the team could win its league’s regular-season title (check!) and conference tourney (check!) and get an NCAA bid (check!). He didn’t pitch a Final Four run, but after all those successes, thriving in the NCAA tourney didn’t feel unusual to the Owls. “To me, winning is winning,” said senior guard Michael Forrest, “no matter what you do or how you do it.”

Recently, the Final Four has started to feature more and more teams like the Owls. In the first 25 years of the 64-team NCAA tournament bracket, only four teams seeded seventh or lower made the Final Four; 11 have done it in the 12 tournaments since. This year is the ultimate WTF bracket: Zero 1-seeds, 2-seeds, or 3-seeds have made it to Houston; three of the four programs left standing had never previously been to the Elite Eight. FAU is playing in the national semifinal against 5-seed San Diego State. Five-seed Miami and 4-seed UConn will face off on the other side of the bracket.

Now, FAU finds itself at the crux of the impossible and the expected. In many ways, the Owls are the least likely team ever to reach the Final Four, coming from a school with a funny name and no basketball history. But the Cinderellas sometimes don’t realize they’re Cinderellas. They know they have a big number next to their name and are playing a team with a smaller number. But they also know they’ve been crushing their opponents for months. We’re surprised to see them winning; they’re surprised that we’re surprised.

I don’t think the kid on Western Kentucky expected his zing to go national. At some point in conference play, an unidentified Hilltoppers basketball player unveiled a nickname for the FAU basketball team: the Beach Boys. “They tried to say we were soft,” said sophomore guard Alijah Martin. “We had to show them that we’re a tough team—pit bulls and Rottweilers.” (“It’s not hard to insult these guys,” May says. “They feel slighted at any misquote.”) But fast-forward to March, and the Owls were chanting BEAAAAAAAAACH BOOOOOOYS! BEAAAAAAAAACH BOOOOOOYS! on a stage at MSG while celebrating a spot in the Final Four.

Before the Final Four run, FAU didn’t have much to go off other than “being near the beach.” Just look at the school’s court, which is decorated with images of palm trees and has the phrases “WINNING IN PARADISE” and “1.8 MILES TO THE BEACH” written on it in big capital letters. (Reserve forward Giancarlo Rosado shouts “YES WE DO GO TO THE BEACH!” when asked, but most of my family lives in Florida and I know the drill—nothing is more Florida than knowing one’s exact proximity to the beach and going like 2-3 times per year.) The thinking seemed to be that perhaps if you focused on the on-court palm trees, you wouldn’t notice the fact that you’re in the 330th-largest venue in Division I hoops. “The campus is a paradise … if you didn’t take anyone to the gym,” former FAU assistant Erik Pastrana told Matt Norlander of CBS Sports. May and Pastrana would apparently try to recruit players without showing them the woeful locker room.

With heaven outside their doors and a hellish gym within, the Owls built something of an identity out of the Beach Boys label—simultaneously pretty and gritty. “We want to fly up and down the court, shoot 3s, play loose and play together. But on defense, we need to play like pit bulls and Rottweilers,” says May. (Yes, May and Martin both said “pit bulls and Rottweilers.” The top sign of a team with top-down buy-in is that everybody has adopted the same catchphrases.) “It’s a pretty cool mix where you have some tough, tough, mean dudes playing loose and free and letting them fly on the other end.” That identity shows up on paper: FAU is tied for fifth in Division I in 3s made this year, but allowed the fourth-fewest assists per game. They play man-to-man defense without a lot of double-teams or helping, just every guy locking down their guy.

Hindsight is 20-20—probably better for owls, with the swiveling heads and the huge eyes—but it’s hard to look back at the 2023 college basketball season and not identify FAU as one of the top 20 teams in the country based on the regular season. Advanced stats show the Owls as a high-quality team. They finished the regular season ranked 26th in Ken Pomeroy’s ratings and 13th in the NET rankings produced by the NCAA.

Some of our most beloved out-of-nowhere Final Four participants of yore had similarly dominant seasons in obscurity. In 2010, Gordon Hayward and Butler went 18-0 in the Horizon League with 13 double-digit wins, then made a run to the national title game that surprised everybody besides the teams that had gotten their asses beaten by them all year. In 2018, Sister Jean watched Loyola-Chicago go 15-3 against the Missouri Valley Conference (and 28-5 before the start of the tourney) only to get an 11-seed. And it’s impossible to make any list of our March Madness heroes without teams with conference records of 20-0 (Steph Curry at Davidson) or 18-0 (the 14-seed Stephen F. Austin team) or 17-1 (Antonio Gates at Kent State) or 16-2 (Ja Morant’s Murray State); teams with overall records like 28-4 (Ali Farokhmanesh’s Northern Iowa squad) or 27-4 (the Cornell team that made the Sweet 16). My big upset pick this year was Furman, which went 15-3 in the Southern Conference and toppled Virginia on a legendary buzzer-beater.

Entering the tournament, the NCAA ignored its own NET rankings and gave FAU a 9-seed. Its logic came down to one thing: FAU hadn’t played good enough opponents, in large part because of the weak makeup of Conference USA. The Owls were the only team from the league the selection committee deemed worthy of a tourney bid. The next-best teams went on to lesser tourneys—yet they dominated those. North Texas beat UAB in the NIT championship game—a C-USA on C-USA brawl—and Charlotte won the CBI. No conference has ever won the College Hoops Postseason Triple Crown before. (Also, nobody has called winning these three tourneys “the College Hoops Postseason Triple Crown” before.)

C-USA’s glory will be short-lived. The conference realignment wave that started with Texas and Oklahoma leaving the Big 12 to join the SEC led to the Big 12 adding three teams from the American Athletic Conference and the American taking six (six!) teams from C-USA, including FAU. Although you wouldn’t know it from their nearly identical names or postseason performances, the American is a big step up from Conference USA. This is the way of the college sports world. C-USA was founded in 1995 with a much more attractive list of member schools—Cincinnati, Louisville, and Marquette all went on Elite Eight or Final Four runs under the C-USA banner; Memphis made the national title game. But the league has fully turned over its membership three-ish times in just 28 years. You have to keep moving up. Everybody does it—including past March Madness heroes like Butler, Davidson, George Mason, Loyola-Chicago, VCU, and Wichita State. In this case, at least, the cash from the increased TV payout has given FAU enough money to give Coach May a contract extension. (I don’t think he thinks it’s career suicide this time.)

After all, the NCAA has made it clear that strength of schedule is just about the main metric it cares about when giving tournament bids, perhaps as a pretense to include more teams from major conferences. Twenty years ago, the six BCS leagues got 24 of 34 NCAA bids—71 percent—while this year the Power 5 and the Big East’s two successor leagues got 31 of 36—86 percent. C-USA used to get between three and five NCAA tourney bids; it hasn’t gotten more than one since 2014. When I wrote about this trend in 2018, I argued that this would likely lead to a world without Cinderellas, one in which the same few conferences got virtually every bid, soaked up more of the available talent, and made the sport duller. Instead, the opposite seems to be happening. College basketball is in its Upset Era. More teams are pulling bigger NCAA tournament upsets than ever, and their runs are going deeper than before.

Even in the Upset Era, though, the balance of power still resides with the teams in major conferences that have better recruits and pro prospects. They still eat up most Final Four spots and virtually every national title. But while building larger and stronger conferences seems logically and fiscally wise, the larger leagues have lost something: The underdogs that don’t realize they’re underdogs. Teams in tougher leagues have a better chance of getting an at-large bid but a worse chance of posting a record like 30-3. And the schools that move up often achieve less NCAA tournament success. (We haven’t heard as much from Butler, George Mason, Loyola-Chicago, and Wichita State. Instead new teams from the leagues they abandoned have stepped up.)

Teams from bigger leagues can achieve stability; teams from smaller leagues can become kings. They can win and win and win, and learn things from winning that you simply can’t learn by going 11-7 in a better league. They begin to believe that if they all do their jobs and have each other’s backs they can achieve the things they say they will. Their confidence and cohesiveness becomes an edge—not more important than talent, but every once in a while, enough. They check off every item on their checklist until it doesn’t seem so ridiculous to write “Final Four” or “National Champions” at the end.

By winning every game for months, FAU learned that it could bring trophies and glory to the tiny gym with the unspeakable locker rooms at the school with no basketball history. After finding success once and twice and 30 times over, they barely noticed how big the stage they were standing on had grown. The Beach Boys learned that the only names that mattered were the ones they called themselves, and that the words written on whiteboards could be more than just magic marker mantras. They were built for that moment at MSG—and they might be built for the next one, too.