How a Kiwi inventor built the first computer

If you can believe it, the world’s first computer was built by a Kiwi engineer in 1913, who graduated from the University of Canterbury and promptly moved to Australia for better wages.

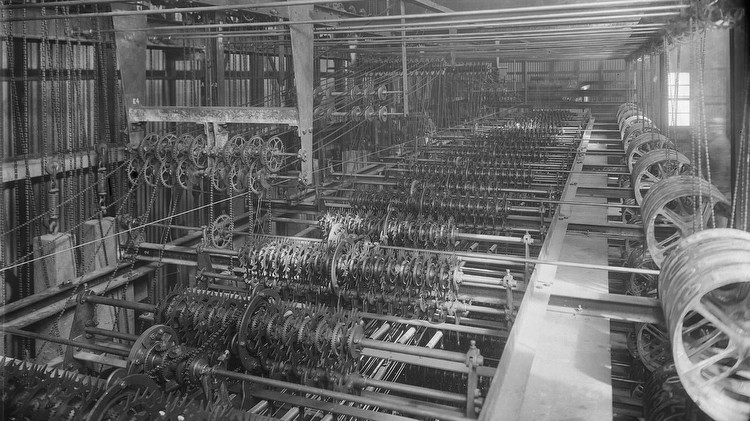

But, we’re not talking about the type of desktop or handheld computer on which you might read this story. This machine was made of gears, cables and pulleys, and took up an entire building.

Instead of chips and transistors it used mechanical functions to compute equations and display them in real time. It was powered by gravity with concrete blocks pulling down cables – a similar mechanism to a grandfather clock.

Engineer George Julius was not a betting man, according to accounts from the time, but built the contraption with his sons in a garage to automate the process of casting and tallying votes in a local election.

Although Western Australia was not ultimately willing to trust democracy to a mere machine, Julius found an adopter in the horse racing industry, specifically Ellerslie Racecourse in Auckland.

Fast-forward to 2023, and the building where Julius’ history-making “totalisator machine” was housed is still within gaze of the Southern Motorway.

“You can imagine the noise of the machines and the smell of cigar smoke and stale beer,” Auckland Racing Club chief executive Paul Wilcox says.

Wilcox explains that punters would place their bet on a given horse with a teller who would pull a lever, affectionally known as a “beer handle”.

There was a handle for each horse connected to a spaghetti network of taut cables that, when tugged, would register a bet.

The totalisator machine would update a large display with numbers on wheels, showing how much money had been placed on each of the 30 horses, thus revealing what winners stood to gain.

It was a unique technological marvel that could handle the input of each teller, make calculations and display the result in real time, all at once, and without electricity.

History appears to have sidestepped Julius’ accomplishment, with most attributing England’s Charles Babbage’s design for a “difference engine” in 1830 as being the first mechanical computer, although a working model wasn’t actually built until the 1990s.

Julius’ technological revolution shaped New Zealand society, illustrated in the more than 100 racecourses at their peak, with about 50 remaining despite the sport’s declining prominence.

It also had huge international success with hundreds of machines installed across 29 countries.

The totalisator machine opened up race betting from being an activity associated with either wealthy members of a club, or dens of bookmakers, to being a sport of the everyday Kiwi - much to the protestation of contemporary moralisers.

Around the time of the machine’s introduction, the Northern Advocate reported that the Auckland Ministers Association alleged to a board of commissioners that it had resulted in an increase in gambling.

“There were people who would bet with the tote who would not bet with bookmakers. The tote lends an appearance of respectability and safety,” the report said.

In 1914, J Pollock of the Wellington Racing Club was quoted saying the tote had been responsible for increasing the stakes and an improvement in courses and racing studs.

“No money was rung up on the tote unless paid through the windows, and it was absolutely impossible for the owner, trainer or jockey to manipulate the machine. The tote staff would first have to be corrupt, and such tricks would be apparent to the merest tyro.”

So prolific was the change, that the government of the day decided to ban all bookmaking and formed a state-owned gambling monopoly – the Totalisator Agency Board, known .

The Auckland Star reported in 1924 that the Labour government had tried to introduce a bill to ban the totalisator, but by then it had taken hold.

“The task of abolishing the tote is no easy one, because while the majority of racegoers would like to see both tote and bookmakers, the chances are that of the two, the machine is preferred.

“New Zealanders, while not confirmed gamblers by any stretch of imagination, are a sports-loving community, and dearly love have to a little flutter.”

In a 1928 letter to the Hawke’s Bay Tribune a Hastings resident expressed that the popularity of the 10-shilling tote was “in strong evidence at the trots”.

“This is a great chance to make this racing club more popular with the bulk of the public. With the present scarcity of ready money, the one-pound ticket debars hundreds from investing on the tote, as they simply, like myself, cannot afford it.”

Ross Hawthorn, a former employee of Ellerslie Racecourse in the 1960s and 70s, says part of the reason it became so popular was that there was bugger all else to do.

“In those days it was ‘rugby, racing and beer’, and racing probably had the same profile as rugby.”

The men would attend in their suits and the ladies would be dressed in their finery and hats, he said.

“I remember in the late 70s we had a jackpot, and it could only be won on the course. It had to be struck once it reached over $50,000, and we had hit $47,000.

“The following Saturday happened to be a stinking wet day in the middle of June, but we did about $1.6 million [in turnover] with everyone who had turned out.

“One of the jokers who won it went to the window to get his ticket paid out, and he walked away with a canvas bag packed with cash. A TV announcer had to tell him to put it away.”

Meanwhile, in the 21st century, the horse-racing industry is on the precipice of another technological breakthrough that bears many similarities to the acclaim and controversy of the totalisator machine.

As the racing industry’s revenues decline in the face of competition from online gambling, the Government announced in May it had approved a billion-dollar deal between the TAB and international digital betting firm Entain.

Racing Minister Kieran McAnulty also said the Government was considering banning online betting outside the TAB, again forming a regulated monopoly.

He said the industry was worth $1.6 billion to the economy and directly employed 14,000 people.

The announcement has been met with criticism from the Problem Gambling Foundation, which remains unconvinced that Entain’s harm reduction technology will counteract the ease of access of betting apps.

Auckland Racing Club chief executive Paul Wilcox says the deal will reinvigorate the industry and attract young talent back to the courses.

“In any industry, change is the one thing that can be guaranteed. Some people will be for it, others will be against.”

He believes that horse racing continues to hold a position in modern Aotearoa alongside mainstay sports like football or rugby.

“People dress up, there is a sense of occasion. You talk to people on the course, and it's the atmosphere, the majestic animal and the intoxication of it all - and I’m not referring to being drunk.”

He says there’s nothing like the sweet smell of sweat on a horse that has just returned from racing on the track.

“For many Aucklanders, it might be their first experience of being up close to an animal like that. A race horse weighs around 550kgs and can run 70kph.”

The golden age of the totalisator machine may be over, in favour of newfangled apps and widgets, but the racecourse hasn’t forgotten its 170-year history.

The tin facade of Julius’ machine’s display was built over when the building was converted into a stable in the 60s, but it was unearthed in 2019 when it was renovated into a function space.

Wilcox says the intention is to retrofit it with LEDs and have it proudly display odds and earnings for present-day punters.

“Everything we do is to advance the sport of racing, but if we lose the history, we won’t get it back.”