How to tank: Getting to the bottom of the NHL standings is more difficult than it looks

Simple question really, but one that rarely gets asked. Or doesn’t get asked enough. Gary Bettman says “nobody tanks” in the NHL. Anyone watching this season knows better.

So while, yes, players and coaches do their best to win, not everyone within an organization might share that mentality. Not when there’s a generational talent up for grabs.

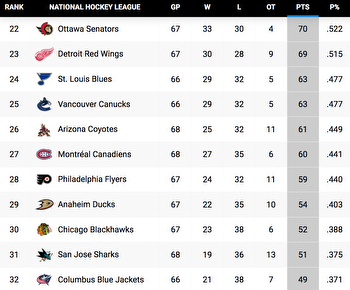

Now that we’re into the second half of the NHL season, the race to the bottom of the standings is going to be scrutinized as closely as the race to the top. It’s all thanks to Connor Bedard, a 17-year-old from North Vancouver currently playing for the Regina Pats of the WHL. The world junior championships illustrated the gap between Bedard and the rest of the 2023 NHL draft eligibles is a chasm.

Cornerstone players don’t come around every year so any NHL team hovering at or near the bottom of the NHL standings can’t be blamed for thinking: If we’re going to miss the playoffs anyway then it’s better to miss them by a lot and increase our draft lottery odds. The chance to draft Bedard could change the direction of our franchise in the same way Mario Lemieux, Sidney Crosby or Connor McDavid changed the direction of their teams.

The NHL introduced the draft lottery in 1995 to discourage teams from actively tanking. Back before the lottery, the team with the poorest record earned the first overall pick. It created an incentive not just to be bad, but to be historically bad. In 1984, the Penguins and Devils competed, to use the term loosely, for the right to draft Lemieux. Pittsburgh finished with 38 points, New Jersey with 41.

The draft lottery has been amended a few times over the years, with the goal of creating at least some level of uncertainty about who picks first though the team with the worst record still gets the best odds of winning.

Hungry young players can be a problem

It’s one thing to say a team is or should be tanking and another to execute the strategy in the real world. Professional athletes are universally motivated to win. It’s in their DNA. It’s how they got to the highest rung of their sport in the first place. And so, sending a message that the goal is to lose a game is hard to do.

“What people forget is, players are fighting for their jobs for the following year,” said former Anaheim Ducks executive David McNab, who spent more than four decades in the NHL, first as a scout and then as a front-office executive. “I think it’s extremely hard to try to lose. You can run guys up from the minors or play different lineups, but I believe it’s very hard to tell a good young player who is trying to get a contract, or enhance his value, to go out and play lousy.”

McNab’s father, Max, had just been appointed general manager of the Devils in the middle of the 1983-84 season, just ahead of the Lemieux draft. That year, without the uncertainty created by a draft lottery, the Penguins selected Lemieux and changed the trajectory of their organization forever. New Jersey got a very good player — Kirk Muller — as a consolation prize, but Lemieux evolved into one of the top five players in NHL history.

According to McNab, his father didn’t talk much about that first year in New Jersey but remembers him “getting s—” from some fans for winning too many games at the end.

“My dad believed you should try to win and out of respect for the game, you had to put the best team on the ice,” McNab said. “You shouldn’t just try to lose. History will always say, that was dumb. Honestly, they weren’t trying to lose, they just did lose.”

Part of the problem was the Devils had a collection of hungry young players in the lineup — including Pat Verbeek, Ken Daneyko and John MacLean — who were just getting their NHL feet wet. That trio eventually evolved into important contributors.

That is the fundamental problem with tanking. Every strategy has its own inherent flaw. So, for example, stripping a team of its best players at the trade deadline, in order to greatly weaken the overall core, is the most common theory cited on social media chatter, in the tank for Bedard. But once you trade away an experienced productive player or two, usually you’re filling it with a young player getting his first or next or maybe even last chance to become an NHL player.

There is a long history in the NHL of teams playing well in “garbage” time. Once the season is really and truly lost, they are critically evaluated to determine if they will be part of the future going forward. And if they play poorly, or half-heartedly, as individuals, that isn’t going to enhance their position in the organization.

If a team is seriously interested in being as bad as possible, they are almost better off playing a lot of jaded veterans, nearing the end of their careers, where the motivation to give their best, every night may be flagging — rather than a hungry youngster, eager to make a positive first impression.

In short, it’s not always possible to create a downward spiral in a game such as hockey, where even the very best players spend more time on the bench than on the ice.

Accordingly, for tanking purposes, the focus needs to fall on the individuals who can most directly influence the outcome of a game by themselves — a team’s goaltenders and its coach.

Bad goaltending and bad coaching are key to a successful tank

If a team gets consistently below-average NHL goaltending from night to night, that can contribute to losing on two fronts.First, you’re usually giving up one or more goals per night that probably should be saved. Second, when that happens on a consistent basis, it discourages all the position players in front of a struggling goaltender. After a while, it becomes pretty clear — via body language — when a team loses confidence in its goaltending. It just sucks the life out of a team and even if as a player your heart is telling you go, go, go! your mind knows all that effort will eventually be for naught because your goalie is going to give up a cheapie or two.

Then there’s coaching. Until this past Sunday, when the Canucks fired Bruce Boudreau and replaced him with Rick Tocchet, no NHL team had made a coaching change this season. Why? Realistically, no team that’s playing well near the top of the standings is going to change its coach this year and no team that’s playing badly near the bottom of the standings (and interested in landing Bedard) should do so either. Think about it. Usually, and almost without fail, a team gets a short-term bump from a coaching change — a new voice comes in, with a new message. No matter what you might have done before as a player, there is now a need to impress the new boss. He doesn’t care what you contributed before. He only cares what you can give them today.

Duhatschek: After botching Boudreau's firing, Canucks need Tocchet to change the narrative

In the short term, everybody immediately snaps to attention — for a little while anyway — and maybe then your team goes on a short run up the standings. But in a year when you’re in Tank Mode, a short run up the standings might be a disaster because it suddenly decreases your lottery odds.

Publicly, it’s an easy thing for an organization to commit to their current coach, at least until the end of the season, on the grounds of being “fair” and giving him lots of rope in order to show his coaching chops.

According to Ray Ferraro, the former NHLer who currently works as a TV analyst for ESPN, the issue of tanking is far more complicated than people are willing to acknowledge.

“Whenever I’m asked (about tanking), my answer is, ‘Well, what exactly is it you would like the management to do?’” Ferraro said. “We can all agree Connor Bedard is a fabulous player and a really interesting story that has led to this tanking talk. But if every second article we read also says that no team has any cap space, how do you propose getting this done?”

In Ferraro’s mind, the presence of the NHL salary cap is a great complicating factor in executing a tanking strategy — simply because any team trying to get worse by dumping a player or two is currently having a hard time finding a trading partner that has the financial flexibility to make it happen.

“You can say, ‘Yes, you should tank.’ However, until you can find a way to make your team bad enough, by getting rid of players and finding someone with the cap space to take them on, you can’t,” Ferraro said. “Here’s the other part: Everybody loves the idea of tanking. Do people really know what that means? Unless you win the lottery and get really lucky, you are now one of the very worst teams in the league. You are looking at years of rebuilding and mediocrity. So, all these fans that are talking about tanking, are they going to buy tickets to watch a bad team? Of course not.”

One team that’s been transparent in notifying its fan base that it believes the future is a few years down the road is the Coyotes. For a couple of years now, the Coyotes have consistently stripped the roster of most of their NHL players and have weaponized their cap space to take on unwanted players on bad contracts from other organizations.

The problem is, they also went out and hired an effective coach (André Tourigny), who is squeezing a lot out of a collection of kids and stragglers, and signed a goalie (Karel Vejmelka), who — until hitting a recent cold patch — was making so many saves above expected he was giving the Coyotes a chance to win practically every time he started.

So, on the one hand, the Coyotes have nicely checked the box on one tanking scenario — trading away top players — but are sputtering on the other two fronts because their coaching and goaltending incumbents were doing such respectable work.Plus, the current iteration of the Coyotes includes many players who are playing for their NHL lives and are motivated to play as well as they can within the context of who they are.

In his two-decades-long NHL career, Ferraro sometimes played for good teams and other times for teams that were mediocre or worse. In 1999-00, he landed with the expansion Thrashers and played there for three seasons. In Year 2, he produced 76 points in 81 games.

Could Ferraro ever remember a time thinking that by playing on an expansion team, it might not be the worst idea to lose a few games down the stretch, to perhaps enhance a team’s draft position?

“The answer to your question is: Never,” Ferraro said. “We’d drafted Dany Heatley. The next year, we were going to get the first pick and everybody knew that was going to be Ilya Kovalchuk. I remember thinking, ‘Well, that’s great, but how the hell does that help me?’ Because the immediacy of your career is you realize you only have a certain amount of time. You just want to have a good year, so you can play again next year. And so, the draft picks, the acquiring of future draft picks, it does you no good. You don’t think, ‘Oh great, in the next three years, we’re going to have three first-rounders.’ Who cares? You’re trying to win tonight.”

If a team were to turn to the goaltending option in its effort to tank, even that can deliver inconsistent results. NHL goaltending can be inherently so streaky that there is no guarantee that even if a team dips into the minors to downgrade its netminding the newly promoted goalie will necessarily deliver the lousy results you need to properly tank.

Every year, the NHL is full of stories involving goalies who have patiently waited their turn for an NHL opportunity and then seized the moment.

This year, Pheonix Copley in LA, Pyotr Kochetkov in Carolina, Charlie Lindgren in Washington, and to a lesser degree, Spencer Martin in Vancouver have been given the best NHL opportunities of their lives and generally made the most of them.

Chicago’s decision to bring in Petr Mrazek from Toronto mostly had the desired effect early. He’s been injured (again) and his numbers heading into January were poor (2-10-1, .878 SP, 4.19 GAA). But then, starting mid-month, Mrazek found his game has produced a number of effective starts, and what do you know? Chicago unexpectedly started winning games — to the chagrin of the portion of their fan base who thought the Blackhawks might have 32nd place sewn up by now.

“Go back to the year before Buffalo got Eichel and look at their goaltending,” Ferraro said. “Anytime somebody won two games in a row, they got rid of them. Because they didn’t want to win. There was one point late in that year, Buffalo lost a home game and the crowd was cheering.”

What's the plan if the Blackhawks don't land Connor Bedard?

Tanks are long and painful, even with a lottery win

Ferraro notes that even if you successfully negotiate your way to the bottom of the standings, and then win the lottery, the job isn’t done.

In fact, it’s only just starting.

“Part and parcel of The Tank comes draft and development,” Ferraro said. “I’m not sure where I heard it first, but it’s true: With draft and development, everybody wants to see the baby, but no one wants to hear about the labor. And so, the draft is exciting. Development? Boring, long, slow, unpredictable.”

And to complete Ferraro’s birthing analogy, usually painful.

“Chicago has maybe done it as well as anybody. But what if you do all that and wind up with the second pick? Or the third pick? Because everyone’s saying, ‘Tank for Bedard.’ But you don’t necessarily get him, even if you do tank. You get a chance to get him. And by the way, the team that drafts him is going to be pretty terrible. The first thing you’re going to have to do, when you draft him, is to spend money to get him a couple of players to play with. Otherwise, the kid could just get steamrolled.

“How is that fair to his growth and development? It’s not. Then the problem is, if you get him and you spend some money to surround him with a few good players and then you get right into that ugly part, around seven from the bottom, and you stay there for another five years. That’s no good either.”

No, it’s not. The reality is, tanking is an inexact science — and easier said than done.

(Top photo of Connor Bedard: Minas Panagiotakis / Getty Images)