Inside A High-Stakes March Madness Calcutta

Professional gamblers wager millions on the NCAA Tournament using an auction-style format that brings out casual hoop dreamers and sophisticated quants. With brackets busted, it still pays to play the game within the game.

Neal, a 36-year-old insurance broker who lives in Ohio with his wife and two children, is the proud owner of the University of Texas, University of Connecticut, Tennessee, Creighton and Florida Atlantic men’s basketball teams. His wife doesn’t know about his ownership stakes, but hopefully by the end of the NCAA Men’s Basketball tournament his $19,000 investment will turn into $50,000. And then, he’ll let her know.

“Right now, we’re on a heater,” he says of the March Madness run his teams are on. “We’re still in the red on paper, but I hope that will change quickly with a few wins.”

Neal doesn’t technically own any team, of course, but the amateur sports gambler “bought” these college basketball squads for the duration of the tournament during a type of sports wagering called a Calcutta auction.

Calcutta pools have been around for more than a century. The practice is said to have started in Kolkata, India in the late 1800s, when British colonists used the format to bet on cricket and other sports that feature single-elimination tournaments. The rules are simple enough: teams are auctioned off to individuals or groups, and the highest bidder “owns” that team for the duration of the tournament. All the money raised during the auction goes to the pot and winners of each stage of the tournament receive a certain percentage of the pot that is predetermined. There is no rake or vigorish, but some Calcuttas take a percentage off the top and donate it to charity.

A legendary golf Calcutta took place for years, between the early 2000s and 2018, at a golf course on Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. According to gamblers who attended, the pot regularly hit $1 million. And one year the game was robbed—crooks snatched $600,000 in cash—but the organizer, a well-connected gambler, put the word out and the money was returned.

Which is all to say that Calcuttas are not generally happening at the local bar or among office workers. It’s a genteel form of gambling practiced by well-to-do risk-takers: doctors, lawyers, and finance guys gathering in rented restaurant dining rooms, boardrooms and country clubs.

For the last nine years, Neal and his college friends hold an auction for March Madness and the Masters golf tournament in April. The group meets virtually while an auctioneer—a friend not involved in the betting—randomly picks a team, announces their seed and starts accepting bids. There’s no fast-talking, gavel-touting barker, but the prices speed quickly past the four figures as gamblers huddle around their laptops, poring over their spreadsheets and mathematical models, spitting out price ranges for each team. The auctioneer awards the team to the highest bidder, and then it’s on to the next team until all 68 are selected. This year, the pot for the Ohio Calcutta hit $130,000 with the highest priced team, the Houston Cougars, No. 1 seed in the Midwest Region, fetching $8,200.

If the Cougars go all the way, the syndicate that owns them will win $24,700, or 19% of the pot, making a tidy $16,500 profit. For Neal, he has one goal: “To make as much money as possible.”At night, he’s been praying for his ideal outcome: “We want to have two of our teams in the championship against one another—a UConn-Tennessee match-up in the final would be awesome,” the insurance salesman says.

Neal knows the odds are against him, but he also knows anything can happen during March Madness. Which is why he doesn’t care about filling out a bracket like most amateur gamblers or pulling out a phone and betting the money line through DraftKings, FanDuel, or any number of the gambling apps. Betting on March Madness in a Calcutta gives bettors more than just skin in the game: it gives a sense of ownership.

“Calcuttas are just so fun and there's nothing like the NCAA tournament,” Neal says. “To have a market-set, ownership stake allows you to ride your team’s wins and get crushed by the losses, all while you sit at home in front of your TV. You get a sense of both excitement and defeat that you don't necessarily have in a standard bet.”

The Men’s NCAA Basketball tournament is one of the most bet-upon sporting events of the year. With 63 games, March Madness rakes in more total handle than the Super Bowl. This year, an estimated 68 million American gamblers are expected to wager $15.5 billion during the tournament, according to the American Gaming Association. Sportsbooks and mobile apps don’t offer Calcuttas—the wagering method plays out in tight-knit groups during hours-long Zoom sessions. There is no reliable estimate for how much is being wagered through Calcuttas, but the AGA’s report found that 32% of American gamblers will wager “casually” with friends. And anecdotally, it’s a safe bet that tens of millions of dollars is being gambled through Calcutta auctions.

For Neal’s Calcutta, the 32 teams that advance past the first round all win 1% of the pot. The schools that make it to the Sweet 16 win 1.25% and those in the Elite 8 get 2%. The Final Four participants get 3.25% while the two teams in the finals win 4.5% just for making it to the last tip-off. The overall champion is awarded 7% of the pot.

But it wouldn’t be gambling without a few prop bets. Most auctions sell “junk teams”—ranked No. 13 through No. 16—in bundles. If you’re looking for value, this is where to concentrate. The team to pull off the largest upset wins 1% of the pot and owning the team that loses by the greatest number of points is rewarded 1.5%. “That's why you typically purchase the No. 16 seeds,” Neal explains. “You're looking for them to get absolutely smoked out the gate.”

The best-performing Calcutta participants are not casual gamblers but numbers-focused quants. Professional sports bettor Rufus Peabody and Jeff Ma, a tech entrepreneur, hold an annual high-stakes Calcutta auction for March Madness. Peabody, who studied economics at Yale and now specializes in golf and NCAA basketball, wagered more than $10 million on college hoops this year. And while Ma has built and sold a few companies, he’s no slouch when it comes to gambling: in the 1990s, Ma was a member of MIT’s vaunted blackjack team and is the basis for the protagonist in the book Bringing Down the House and the film 21.

For Peabody and Ma’s March Madness Calcutta this year, the first team auctioned was Arizona, the No. 2 seed. Within minutes, the Wildcats were bid up from a few thousand to tens of thousands of a fictional cryptocurrency they dubbed “Rufus Coin.” The pot hit 1.28 million Rufus—and while they would not reveal the conversion rate, they are not fooling anyone. The group of professional bettors wouldn’t be wasting their time if there wasn’t big money at stake.

But Peabody’s action in this Calcutta only represents less than 0.1% of his annual gambling. For him, the auction is all about fine-tuning his betting models and simulators he and his partner, who did not want to be named, built and use during the regular season. There is no room for favorite teams; it’s all about the numbers. “We trust the process,” says Peabody, who, not coincidentally, hosts a podcast with Ma called Bet The Process, “If there's issues with it, we refine the process. We’re not saying, ‘Oh, I have this gut feeling.’”

Peabody’s proprietary software simulates every game 50,000 times, down to every possession, the length and how many points a player will likely score. Peabody and his partner also model the prices for each team and take into account injuries and variables like how a certain team has performed under various circumstances.

“We're able to select a suggestion based on the probability and run through a game,” says Peabody. “We take it through the entire tournament that way. Calcuttas are an interesting mix of handicapping and game theory, and they’re social.” Peabody adds: “They’re a fun sweat, as well.”

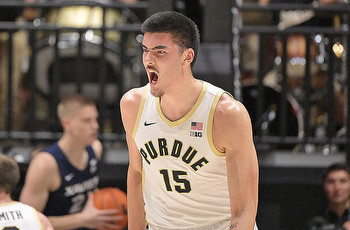

He has already been sweating many of this tournament’s bets. Peabody bought Purdue, who lost in the first round. And he’s still very much in the red. He bought a total of nine teams and only two remain: Miami and Gonzaga. He needs one of them to win the championship to be in the black.

As for Ma, who owns No. 2 seed Texas, a 50% stake in No. 1 seed Houston and 50% of another No. 1 seed, Alabama, he’s also in the red and hoping for a finals matchup between two of his teams to be profitable. Ma says some sharp bettors love driving up the price of the market and finding value by squeezing the squares on the money line in a traditional bet. But the fun thing about Calcutta is that it’s also a brain teaser. Modeling for the point spread has been figured out, but Calcuttas require gamblers to solve problems that haven’t been done before. And while you can get away with betting on your gut, Ma suggests using your brain.

“If you don't have a computer model, you are at a huge disadvantage,” he says. “But these things are majority luck based, so anyone could come in and do fine. Over time, though, you’re not going to do great if you don't have a real math model.”