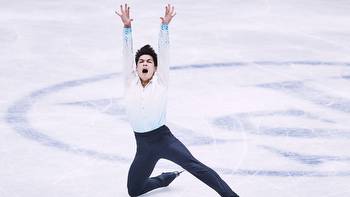

Jason Brown returns to figure skating with 'Impossible Dream'

In June, figure skater Jason Brown moved all his belongings out of the Toronto basement apartment where he had lived most of the last four years while training to make the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. He brought everything back to his family home north of Chicago, where nearly all those possessions – and his car – remain.

“No part of me thought I was coming back to Toronto,” Brown told me in a recent phone conversation.

Why would he have? Brown, 28 next month, had been in Toronto to work with coaches Tracy Wilson and Brian Orser on preparing for competitions. That lengthy phase of his skating career, with 12 years as a senior competitor and suitcases full of medals and achievements, seemed to be over with his solid sixth-place finish in the men’s singles event in China.

Brown had wearied of the blinkered perspective and single-minded focus necessary to be an elite competitive skater. He wanted to immerse himself more deeply in the other sides of skating, using his nonpareil artistry and body awareness to be a choreographer, to be a frequent and innovative show skater, to lay groundwork for the hope of one day producing his own show and having a skating camp.

None of those endeavors needed him to be based in Toronto.

And yet there he was in Toronto when we talked, back in the basement apartment with one suitcase of belongings, back training at the Cricket Club for his next competition, the U.S. Championships in late January, back with a frame of mind in which skating at the 2026 Winter Games is a far-off but not far-fetched thought.

It is a thought he will allow to cross his mind as long as the process to get there isn’t the same as it ever was, with the repetitiveness of that Talking Heads lyric.

“If I can do it on my own terms and it proves to be successful and healthy for me, it (2026) is totally a possibility,” said Brown, a two-time Olympian and 2015 national champion.

“I’m not going to keep coming in every day and drilling the technical again and again and again. I want to give myself the freedom to do it on my own terms and in my own time.”

To that end, he has spent some time this season choreographing a short program for Italian Olympian Daniel Grassl, European silver medalist last season. And some time on the sidelines at Skate America, doing on-camera interviews for Team USA, a role he would like to expand upon.

He will go home to the Chicago suburbs for 10 days around Thanksgiving. He will go from there to do two shows on the East Coast in December, go back to Toronto for two and one-half weeks, return to Chicago for Christmas week and then leave for Japan to do six shows after New Year’s, returning to Toronto three weeks before the men’s event begins at the 2023 U.S. Championships in San Jose.

(Whew.)

Brown skipped the current Grand Prix season and does not plan to compete before nationals.

“If I’m going to do it my way, there is no point in rushing anything,” he said. “Before, it was always, ‘I need to be ready for this event right now.’ This season is about how we adapt to this new method of (intermittent) training and competing – not just me, but my coaches and my (physical) trainers.

“We haven’t done enough work yet to see how this translates. It could blow up in my face. It could be an utter disaster. But I don’t have it in me to keep doing it the way I had been.”

He had skated impeccably at the 2022 Olympics, getting personal-best scores for the short program, the free skate and the total, earning positive grades of execution on all 19 elements and finishing fewer than two points from fourth place. When it ended, in the Covid-cloistered Beijing environment, Brown had trouble processing what he called a “bizarre experience.”

“I remember finishing and thinking, `Is it over? Is this how it ends?’” Brown said.

The idea of competing again took shape after he was invited to the Japan Open, a low-pressure, free-skate-only team event in early October that included active competitors and “retirees.” The chance to compete in it for the first time attracted him, so he put together a new program to “The Impossible Dream” with his longtime choreographer, Rohene Ward, and returned to Toronto to train for three and one-half weeks with Wilson.

“We thought, ‘Let’s use the Japan Open as a gauge,’” Brown said. “Is competing something I still have a little bug to do? Or do I go there (to Japan) and say, ‘It was a great chapter, but this is not for me?'”

He skated respectably if not flawlessly at the Japan Open and realized he still had a love for competition, a feeling magnified by how good he felt physically. His regular off-ice sessions, both virtually and in person, with core movement specialist Lisa Schklar had kept him energetic and healthy while doing 50 shows between April and August. So on Nov. 2, he announced on Instagram that he would be competing at 2023 nationals.

“Coming back was not in my mind in the summer, but after finishing the shows I felt great,” he said. “I have more energy than ever.

“The team around me makes me love it even more and makes me want to push more and more – and my body is holding up.”

Brown, who has not landed a quadruple jump with a positive grade of execution in competition, was sure his quad attempt in practice the day before the Olympic free skate would be his last. Then he attempted one last week.

I asked Brown in a text message after our conversation whether he had landed that attempt. “Hahaha no,” he replied, followed by two laughing emojis, “but I never thought I’d have the drive to even want to try one!”

With reigning Olympic champion Nathan Chen and reigning world bronze medalist Vincent Zhou sitting out this season to concentrate on college, Brown should need no quads to be a strong medal contender at nationals in San Jose. His Japan Open free skate score is second best (easily) by a U.S. man so far this season, and the relatively lesser impact of quads in the short program has always worked to his benefit.

Brown said the absence of Chen and Zhou had no influence on his decision to compete at nationals. He actually had written to both, asking lightheartedly, “Do want to come back with me? Reunion?” Both told him they would be there to cheer him on – from the stands.

The @quadg0d, Ilia Malinin, will be a heavy favorite to win his first U.S. title after finishing second last year. Malinin, 18 in two weeks, lived up to his social media handle by becoming the first person to land a quadruple Axel in competition, first while winning the U.S. International Classic in September and again – with near perfect execution – while winning Skate America in October. His free skate and total scores lead the world this season.

At all his national meets from 2014 on, making the Olympic or world team was Brown’s objective. That will not be the case this time, even though Brown said he would be thrilled to compete at the 2023 World Championships if his skating earns one of the three U.S. men’s singles places.

“This isn’t about some unfinished business or an outcome or the need to do `X’ to prove myself,” Brown said. “It’s just out of love for the sport and the challenge of trying to better myself.

“There is nothing where I am saying, ‘I need this to feel finished.’ I am so proud of my career.”

Who wouldn’t be, with a record that includes: two Olympic appearances (and a team bronze medal); a U.S. title (and five other medals at nationals); four senior world championships appearances (with a fourth place in 2015); three junior world championships appearances (two medals), nine Grand Prix Series medals (one Grand Prix Final appearance); a Junior Grand Prix Final gold medal; and nine Challenger Series medals (six gold).

Brown has earned a lot of that hardware since his self-proclaimed rock bottom at 2018 Nationals, also in San Jose, where he cost himself a spot on that year’s Olympic team. At the time, he thought that hearkened the end of his competitive career, but a total break from the sport for six weeks, followed by a coaching change and the move to Toronto, reinvigorated him.

“I am shocked even to have this conversation about going to San Jose five years later,” Brown said.

Over those years he has become one of the sport’s biggest spectator favorites, especially in Japan, where his fluency in the language has added to the fans’ admiration of the purity and expressiveness of his skating. From crossovers to spins to split jumps to spirals to footwork, his skating skills are consummate. He had attracted the world’s attention with an easy-to-appreciate, upbeat “Riverdance” program in 2014 and has kept it with his refined interpretation of subtler, more internalized programs.

His short program this season, to a piano piece called “Melancholy” by Alexey Kosenko, falls into the latter category. He and Ward choreographed it in 2020, but Brown never has used it in a live competition. The music is moody and reflective, allowing Brown introspection over his career.

He sees the “Impossible Dream” long program as a statement that the dream is impossible only if you stop believing in yourself.

Competing in a third Olympics, 12 years after the first, might seem like such a dream. Nationals could be a form of reality check – but not necessarily a decisive one.

“At this point, let’s see if I can show up at nationals after not competing and see how it goes,” Brown said. “Beyond that, it could be, ‘I’ll see you again at nationals in 2024’ or ‘I’ll do the Grand Prix next season or ask for one senior B event and then do nationals.’

“Let’s see how this all unfolds. I have never done it before with blinders off. Can I manage it? If so, there is a huge possibility that 2026 could turn into a goal.”

Philip Hersh, who has covered figure skating at every Winter Olympics since 1980, is a special contributor to NBCSports.com.

OlympicTalk is onApple News. Favorite us!

![[ICE TIME] Japan Championships Filled with Intriguing Storylines as Skaters Vie for Olympic Berths](/img/di/ice-time-japan-championships-filled-with-intriguing-storylines-as-skaters-vie-for-olympic-berths-5.jpg)

![[ICE TIME] Shoma Uno Back in Spotlight with Triumph at NHK Trophy](/img/di/ice-time-shoma-uno-back-in-spotlight-with-triumph-at-nhk-trophy-2.jpg)