PDC World Darts Championship: In bed with Phil 'The Power' Taylor

It is dark in Phil Taylor's hotel room. But I can just about make him out through the gloom. Slumped on his double bed, face low-lit by the snooker on his telly.

There is an awkward moment as I rummage through my bag, attempting to locate my pad and pencil. Wondering if Phil is going to get up, wondering if Phil is going to turn a light on. But Phil remains resolutely bound to his bed.

"Where shall we have our chat?" I ask, assuming we'll repair to the sofa on the other side of the room. Phil pats the sheets, pulls the cord on his bedside lamp and I dutifully climb aboard.

Taylor is in town for an exhibition, at the Frontier Club in Batley. The Bee Gees, Dusty Springfield, Tom Jones - they all played here in the West Yorkshire venue's heyday. Now they flock to see the greatest chucker in history, a capacity crowd of 1,400 darts fans, drawn in by "The Power".

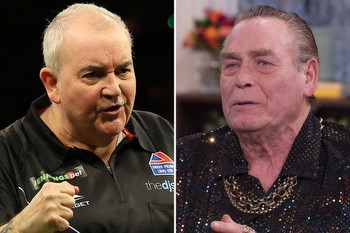

Taylor, 53, doesn't look particularly powerful just now. Surrounded by unpacked luggage, decked out in a tracksuit, he looks worn out and crinkled. He looks how he describes himself: "A bog-standard person, a normal working man."

But this bog-standard person is arguably the most enduring talent in sport. Even if you are of the belief that darts is not a sport, you have to admire his indefatigability.

He has been the best at what he does for a quarter of a century, a man who has transformed his discipline. Because darts hasn't always been like this, a riot of booze and fancy dress, every night a giant stag and hen do combined.

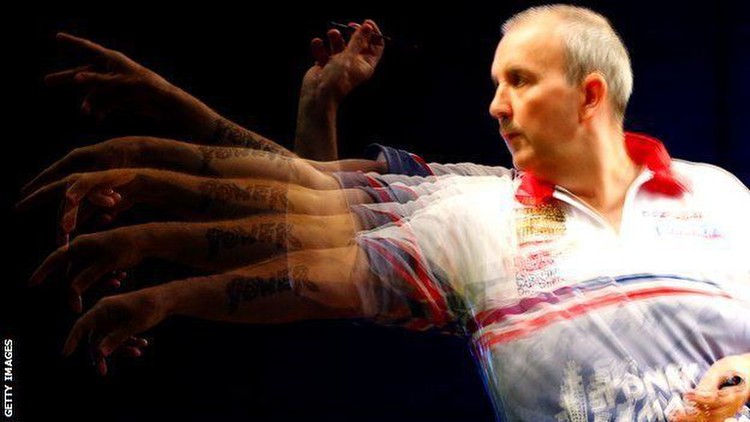

"When I first started doing exhibitions," says Taylor, who is odds-on favourite to win his 17th world title in the Professional Darts Corporation (PDC) version of the event, which gets under way on Friday, "you'd have 20 people down the pub. If you were lucky.

"If we went to America for a tournament, we'd have to get to the final just to get our money back. We'd go down the butchers and buy a loaf of bread, some butter, some boiled ham and some bags of crisps for dinner.

"But when we played in Sheffield this year there were 16,000 in the arena. I was looking out at all these people and thinking: 'Now I know what it feels like for these pop stars.' My grandkids tell me: 'Darts is trendy now, granddad.'"

Taylor's capacity for regeneration is such that he should ditch "The Power" and start calling himself "The Time Lord". Having taken up darts in 1986, turned pro in 1988 and won his first world title (the British Darts Organisation version) in 1990, Taylor has done battle with and seen off several generations of throwers.

As the late, great darts commentator Sid Waddell memorably put it: "If we'd had Phil Taylor at Hastings, the Normans would have gone home."

First there was the Eric Bristow-John Lowe-Jocky Wilson triumvirate which was in the vanguard of the sport in its 1980s boom years. Bristow, Taylor's mentor, won the last of his five world titles in 1986 and packed the game up professionally at the age of 43 in 2000.

"It seems like another lifetime," says Taylor. "I used to watch the likes of Eric and 'Lowey' and think: 'I'll be different to that lot.' I didn't do the drinking and I was more dedicated."

Next was Taylor's rivalry with Dennis Priestley in the early years of the PDC circuit, following the sport's great schism in 1993. The pair went toe-to-toe in five finals, Taylor winning four of them.

There followed rivalries with John Part, Raymond van Barneveld, Adrian Lewis and latterly Michael van Gerwen, the 24-year-old from the Netherlands whom Taylor beat in the final of the 2013 PDC World Championship.

"I can still see things they're doing wrong," says Taylor, a sly grin appearing on his face. "But I'll not tell them." Although Taylor does suggest many of the new breed practise too much.

There have been slumps, but only by Taylor's standards. He was written off by many in 2007, when at one point he failed to hold any of Sky's major televised titles, for the first time since 1994. But he came barrelling back, winning almost everything there was to win the following season.

The doom mongers were at it again in 2012, when he failed to reach the last eight of the PDC World Championship for the first time in his career. But Taylor got sharpening those arrows and has won 11 titles since.

If you want to know the real secret of Taylor's drive and longevity, you have to know something of his formative years in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent.

"My mum and dad worked in the pottery industry," says Taylor, an only child. "Dad didn't earn a big wage but even if he was really ill he'd go to work. Mum was nuts - you'd get a bucket of water over you if you refused to get out of bed.

"I worked as an engineer before going into ceramics, making insulators. It was my job, so I got it done. But I also had a lot of pride in myself. I remember my boss telling me I'd done this thing wrong - I could have crawled up my own backside. I told him: 'Derek, it will never, ever happen again.' And it didn't.

"When I turned pro I was married with four children, so I had a lot more incentive to be better. That's why employers like blokes with a family - they know you'll do the job well because you need to feed them."

An addiction to perfection doubled as an addiction to winning once Taylor committed himself to darts. "The money has always been second to winning," says Taylor, who has won more than 200 tournaments, including 80 major titles.

"I couldn't even tell you what I'm worth or how much I've got in the bank. It's the fact your reputation is on the line and the fear of losing that keeps you going.

"I can't play tiddlywinks without trying my best. My daughter beat me at pool once and I went down the pool hall for 10 days on the trot, so that I'd get her next time. That's life, isn't it? It's all about winning."

Taylor has a holiday home in Tenerife, another near Blackpool and has invested wisely in property. He comes over all wistful when talking about retirement - "I can't wait, the plan is to follow the sun" - but you sense he is also addicted to the adulation and revels in the fact darts needs him more than he needs darts.

"Last year [PDC chairman] Barry Hearn asked me to do another five years," says Taylor, "because Sky gave him £20m on the condition I'd stick around. So I'll keep going, if I can. I do feel a responsibility, to keep the sponsorship coming in and the interest up. Every interview, every article in the newspaper is based on me.

"And it's a lovely feeling when you're up there and everyone is cheering you on. It's something you get used to. It's like love, ever so weird."

But fame has its downsides. In 1999, Taylor was accused by two female fans of "indecently groping" them in his camper van. A devastated Taylor, who denied the claims but was made to pay a £2,000 fine, says he contemplated suicide.

Earlier this year, Taylor was accused of cheating by his old pal Bristow. During a match against Dean Winstanley in Gibraltar, the referee failed to see what the television cameras did not, namely that Taylor's attempt at a double 12 had missed.

"When they were calling me a cheat, that was wrong," says Taylor, looking hurt. "It was a shadowy board and I thought it was in. I offered to forfeit the game or replay it and Dean didn't want that. But everything I do will be scrutinised.

"When you're famous, your life's not your own any more. You've got to be careful in everything you do, everything you say gets taken out of context. But I'm just a dart player. I've been with Robbie Williams and seen his fame."

I had read that Taylor was something of a name-dropper. But the truth is he is just as likely to mention his old friends Bert and Glenys or the bloke who teaches him how to cook Indian food ("I'll give you his number") as he is to mention his good mate Robbie, which is actually quite endearing.

Taylor beams when I mention his Sports Personality of the Year runners-up finish in 2010. It suggests that Taylor, despite his monumental success in his chosen sport, craves the acceptance of the wider sporting community and those members of the public who dismiss darts as nothing more than a glorified pub pastime.

"I was absolutely made up," says Taylor, grinning from ear to ear. "It was bigger than winning the World Championship. David Beckham giving me the thumbs up, all the Ryder Cup lads standing up and applauding me - it was ever such a nice feeling, the best I've ever had. And very humbling."

Taylor and darts have nothing to be humble about. Under Hearn's stewardship, darts has become one of sport's greatest - and most unlikely - success stories.

Packed arenas, big prize money (the winner of the PDC World Championship will pocket £250,000 next month, £50,000 more than this year) and healthy viewing figures (1.27 million tuned in to watch this year's final between Taylor and Van Gerwen) - darts has come a long way from its crisp sandwich days.

No wonder Taylor looks worn out. He's been there every step of the way. Raising standards, raising the profile, changing the game. But seven tournament wins in 2013 suggest "The Power" has plenty more battery life left, even if he does have to recharge more often nowadays.

"Is that it?" says Phil when I declare our pillow talk over, an hour after it started. And with that, Phil finally rises.

"I'd hate anybody to say I made them feel inferior," he adds as he ushers me to the door. Phil, trust me, it's not every day I interview a 16-time world champion in bed.