Shock, anger and transfer market concerns

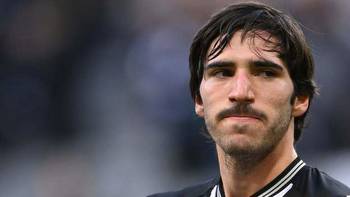

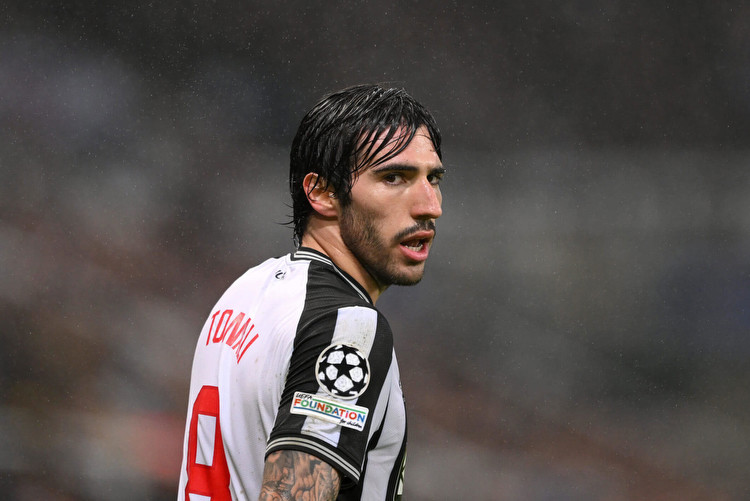

As Sandro Tonali made his final appearance for a long time in Newcastle colours under lashing rain on Wednesday night, the fans in the Gallowgate end of St James’ Park sang about drinking Moretti and eating spaghetti.

Supporters have rallied around the Italian as if he were one of their own, a Geordie, rather than an expensive new signing whose only meaningful contribution since a debut goal against Aston Villa in August is a ban that rules him out of football for 10 months.

Compassion for Tonali has not been confined to Tyneside.

The president of the Italian Football Federation (FIGC), Gabriele Gravina, whose organisation handed out the suspension, vowed not to “abandon” him and the other players caught up in the current betting scandal. Gravina likened them to his “children”.

National team head coach, Luciano Spalletti, initially took the high ground, arguing in strong terms that those involved should “pay” if wrongdoing is proven. Then, once his indignation at how much his preparation for this month’s pair of European Championship qualifiers had been disrupted by police showing up at Italy’s training ground and how the privilege of playing football had apparently been taken for granted and compromised passed, he climbed down a little. Spalletti, who named Tonali in his first starting XI as Italy boss against North Macedonia last month, promised to stay in the 23-year-old’s life when the spotlight inevitably moves on and his darkest hour ticks by.

This sentiment was echoed by Tonali’s coach at previous club AC Milan, Stefano Pioli, who went even further. Initially “shocked and surprised” by the news, he said: “If my love for Sandro was 10 in the past, now it’s 100. He knows I’ll be there for him if I can be of any help.”

Sympathy, however, has by no means been universal.

“Bet on football?,” Paolo Di Canio, a former player with West Ham, Lazio and many more clubs, said on Italian TV’s Sky Calcio Club, a fireside chat among ex-pros screened late on a Sunday night. “There can’t be anything up there (in their heads). You have got to be stupid. Coglioni!” Idiots.

His fellow guest, the ex-goalkeeper Luca Marchegiani, struck a quieter but equally disappointed tone after watching the applause Tonali received when he came on at St James’ Park last weekend against Crystal Palace. “Starting from the premise that you can’t bet on football, I can’t empathise with these players too much,” he said.

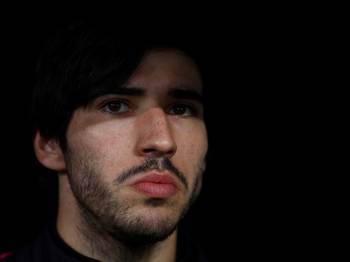

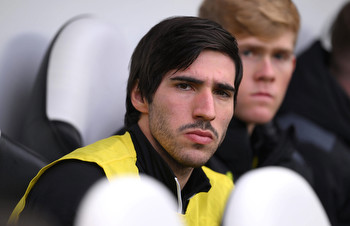

The FIGC’s sporting justice code is clear. Gamble on football and players risk a minimum three-year ban. Tonali and Juventus’ Nicolo Fagioli have received lenient treatment on the basis they turned themselves in to the FIGC, cooperated and struck plea bargains that made rehabilitation and community service part of the sentence. Tonali’s ban is nominally for 10 months, Fagioli, who ran up €2.9million (£2.5m, $3m) in gambling debts, got one “lighter” still at seven months.

GO DEEPER

Spiralling debts and threats 'to break your legs': What Fagioli's deposition tells us

For Zdenek Zeman, the outspoken coach who called out the alleged abuse of pharmaceuticals in football in the 1990s, the FIGC developed a braccino corto — the short arm of the bottler — when throwing the book at the pair. “We’ve always got to have a scandal,” the perennially jaded Zeman said. “Otherwise, we’re not in Italy. It’s a terrible thing. The minimum ban is for three years. But in Italy, it is not respected.”

Gravina, who has faced calls to stand down, highlighted the need for an uneasy juxtaposition between showing sensitivity for those suffering from addiction and the need for sporting integrity. Using an unlicensed and therefore illegal online betting platform is punishable, in most cases, by a fine. This is what the players risk in the criminal case being pursued by public prosecutors in Turin, a case that is not focused on football but on the bookies who run these platforms and their backers.

To Gravina, it seems the gap between a fine in the criminal justice system and a three-year ban in the sporting justice system is too great, particularly if the player involved has an addiction and, unlike past betting scandals, there are no suggestions here of match-fixing.

He alluded to the hypocrisy of a holier-than-thou attitude in a country where ludopathy — gambling addiction — is on the rise. “It’s a scourge on society,” Gravina said, “not (just) Italian football. It affects 5.1million people, and 1.5m are really ill. It is normal that people involved in the world of football are among them.”

The Dignity Decree passed by the Italian government in 2018 was supposed to help. It banned “any form of advertising” from betting companies and forced clubs in Italy to cancel front-of-shirt sponsorship deals overnight. It’s estimated €100million in revenue was wiped out.

But anyone who watches football on TV or online (via DAZN) in Italy will still see odds and betting lines read out as part of pre-game coverage. This is because AGCOM, the communications regulator, considers odds to be information — prompts for studio debates, the same as in-game stats — rather than advertising. This fudge has allowed clubs to strike partnerships with betting companies under the guise of infotainment. As such, while the firms’ branding does not appear on players’ jerseys, it still flashes up on the advertising hoardings surrounding the pitches on which they wear them.

This comes after clubs lobbied the government, via the FIGC, to loosen up the Dignity Decree at a time when other revenue streams, including gate receipts, dried up during the Covid-19 pandemic and broadcasters demanded a rebate.

Accusations of hypocrisy have been made as the game now reckons with a gambling problem. Detractors of the Dignity Decree also argue that the relative lack of visibility for established and licensed betting companies has made it more difficult for the general public to discern which online platforms are legal and trustworthy and which are illegal. An Ipsos Italia study shows that of 21million bettors, a chunk as big as 4.4m — or 17 per cent of the total — have gambled with an unlicensed one.

So work needs to be done on education and awareness.

Within football, Serie A organises an Integrity Tour and summer workshops to reinforce messaging on the rules players must abide by. In his deposition, Fagioli could not reproach Juventus. He told FIGC prosecutor Giuseppe Chine that his club had “informed us it was forbidden to make legal and illegal bets on football” since his earliest days in the academy. “Clearly, informing them has not been enough to create antibodies,” Umberto Calcagno, president of the AIC, the players’ union in Italy, said. “The system has done a lot but the world of football can’t resolve this on its own.”

In the meantime, the betting scandal that threatened to enlarge and engulf Italian football has, at least for now, lost some of its momentum.

Fabrizio Corona, the notorious paparazzo who outed Fagioli and Tonali, claimed to newspaper Corriere della Sera that “at least another 10 players” and “five or six agents” are involved. He subsequently named another four footballers. But none are under investigation by public prosecutors in Turin, or the FIGC. All have issued vehement denials and two of them, Roma’s Stephen El Shaarawy and Nicolo Casale of Lazio, have already begun legal action against Corona for defamation.

El Shaarawy broke down after scoring a last-minute winner against Monza at the weekend. He called his tears “liberating” and said with red, anguished eyes: “There was the anger at hearing stories that weren’t true. I’ve always been a professional. I’ve never once thought about showing this job — my passion and the sport I love — a lack of respect.”

As for Aston Villa’s Nicolo Zaniolo, who was granted compassionate leave from international duty, along with Tonali, when police visited Italy’s Coverciano HQ to place him under investigation, he spoke to public prosecutors in Turin on Friday.

Zaniolo’s case is different from those of Fagioli and Tonali.

His legal team claims he played only online card games and was unaware the site he used to do so was illegal. He did not, his lawyers say, bet on football. As such, unless new information emerges from the examination of his electronic devices, he does not risk a ban from the FIGC, only a fine as part of the criminal investigation.

The scandal has understandably kickstarted a conversation about betting, football, addiction and rehabilitation.

Beyond the players and the duty of care for them, it has also led clubs to wonder about what the affair does for the image of Serie A. The most expensive Italian player ever is now banned for 10 months just nine games into his first season in England. Are Premier League teams, for instance, going to think twice about recruiting players and executives from Italy?

Considering how dependent teams in Italy are on player trading, the prospect of clubs from the richest league in the world being discouraged from spending their riches there is not a welcome one.

Particularly as Serie A’s financial position just got weaker with the new domestic TV deal going for less money than the last tender and the tax breaks included in the Growth Decree, which helped attract stars, being rolled back.

The ripple effects of this scandal could stretch to the next couple of transfer windows.