The MLB umpire who didn’t always call them like he saw them

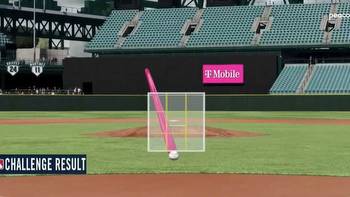

At its annual Futures Game, Major League Baseball last month showcased not just tomorrow’s prospects, but possibly the future of umpiring, by testing out its automated ball-strike system, known as ABS.

The sport has already injected technology into umpires’ calls with instant replay review, but “robot umps” calling balls and strikes would take it to another level. Throughout baseball’s long history, a ball or strike has never really existed as objective truth, the way it does on a spray-painted stickball strike zone. Instead, like beauty, it’s always been in the eye of the beholder — the home plate umpire.

As Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem, who worked National League diamonds for much of the first half of the 20th century, famously said to a batter, “Sonny, it ain’t nothin’ till I call it.” Indeed, umpires have been calling their own strike zones for more than a century — perhaps none as unapologetically and colorfully as the late Ron Luciano.

While little known to a new generation of fans that loves to critique human officials, Luciano provided a rare look into how at least one umpire in one era approached his craft. In his humorous 1982 hit book, “The Umpire Strikes Back,” Luciano admitted he favored the high strike over the low one.

“And, as I gained more weight, the higher strike,” added Luciano, a 6-foot-4-inch, 300-pound former Syracuse offensive lineman, who had been drafted by the Baltimore Colts. “Bending down to call the low strike was something I did not enjoy.”

In the book, which he wrote a few years after retiring, Luciano was open about the challenges of umping the dish: “An umpire working the plate has to make between 250 and 300 ball and strike calls every game, and many of those are so close a surgeon with a scalpel couldn’t split the difference.”

Luciano claimed that he’d sometimes outsource ball and strike calls to catchers he considered honest, such as Elrod Hendricks, Ed Herrmann and John Roseboro:

Luciano wrote that none of those catchers ever took advantage of his trust, and that he’d take back control if the game was close in the late innings.

Robot umps don’t just threaten to make human ball and strike calls obsolete. They’d also make irrelevant a catcher skill called “framing” — the practice of a catcher moving his glove back into the strike zone after a pitch to try to steal a call. Today, that technique is considered an art form. But back in the 1970s, umps found it annoying, Luciano recalled.

“Obviously I couldn’t trust every catcher,” he wrote. “I know it is hard to believe, but some of them will actually try to cheat. A lot of young catchers in particular try to ‘pull’ pitches, or quickly move their glove after catching the ball to make it appear to be a strike.”

“It is their belief that the glove is quicker than the eye. It isn’t,” Luciano added. “‘You pulled it,’ I’d explain, ‘and don’t do it again.’ This is something that umpires really dislike.”

Luciano’s outsize field personality — he’d call runners “out-out-out-out-out!” — was belied by his passion for birding. “I go by myself deep into the woods, and listen to the silence, and think, and watch the beauty of nature,” he wrote. “Then I’m able to go back to the ballpark.”

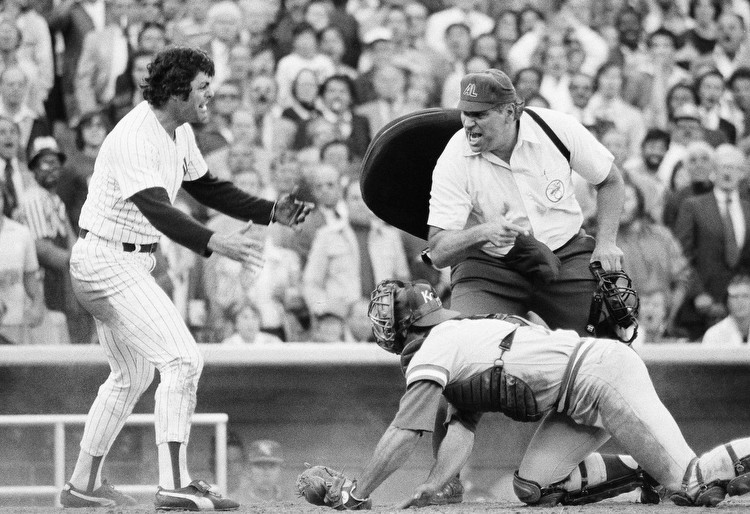

Despite his love of birds, he had no fondness for Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver. Balls and strikes were one flash point in a long-simmering feud between Luciano and the fiery skipper, who at 5-feet-7 was nearly a foot shorter than the ump. Their blowouts were so legendary that Luciano once threw Weaver out of both games of a doubleheader. Before the second game, Luciano recalled, Weaver lectured him, “Now Ron, I want you to take this game seriously. I want you to call balls and strikes the way they’re supposed to be called.”

“Earl,” Luciano responded, “I don’t know how to tell you this, but it doesn’t matter what you think, ‘cause you’re not going to be here to see it.” Then he tossed Weaver. The American League eventually stopped putting Luciano on Orioles games.

And even though Luciano umpired decades before baseball implemented instant replay challenges, he recalled something he dubbed “Earl Weaver’s Instant Replay Signal System,” in which the Orioles would put TV monitors of a closed-circuit TV system in the clubhouse. When there was a close play on the field, someone would run into the clubhouse to check the replay, then relay it to a coach in the dugout. Today, that procedure is pretty close to how teams decide whether to challenge an umpire’s call. But back then, it was to let the famously volatile Weaver — who was ejected nearly 100 times in his career — know how furiously to argue with the umpire.

“They had one signal if the umpire was correct, another if he was wrong,” Luciano wrote. “If the replay showed the umpire had blown the play, Weaver would be all over him; but if it showed the umpire had made the right call, he'd leave after putting up a perfunctory fight.”

Back then, instant replay couldn’t be used to overturn a call, but it could make an umpire’s life difficult. Luciano recalled calling out base runner Leroy Stanton at a game at the Kingdome in Seattle. Stanton started to jog off the field, but then saw the replay on the stadium scoreboard.

“You saw that. He never tagged me,” Stanton shouted at the ump.

“Yeah. I mean no,” Luciano replied. “I saw the real play, but not the play they showed up there. I mean, I saw that one too, but that wasn’t real.” He wrote that he was trying to confuse Stanton but wound up confusing himself.

Luciano also confirmed what many fans and broadcasters have long suspected — that pitchers with good control get the benefit of the doubt on close pitches. He cited a pair of star ‘70s hurlers, Catfish Hunter and Ron Guidry, who were always around the plate.

“The umpire becomes so used to calling strikes that it’s difficult to call a ball,” he admitted. “Strike one, strike two, foul ball, it’s close to the plate, strike three.”

Hitters with good batting eyes, like Rod Carew, would get those breaks too.

“The great hitters get treated that way because they’ve proven they know the strike zone,” he wrote. “If Ted Williams didn’t swing at a pitch, it was a ball, wherever it was.”

At the July 8 Futures Game, players were able to challenge called balls or strikes, with the ABS system rendering the verdict like a courtroom judge ruling on an attorney’s objection. This season, MLB is trying out that version along with full ABS at all Class AAA stadiums, alternating between the two systems.

Several years before baseball started experimenting with robot umps in the independent Atlantic League, then-circuit judge Brett M. Kavanaugh delivered a speech called “The Judge as Umpire: Ten Principles.” In it, the future Supreme Court justice declared, “We do not design our own strike zones.”

With apologies to Kavanaugh, umpires have been doing just that for 150 years. But that human element could soon be gone from the game, yet another evolution for a sport with a reputation for resisting it.

Luciano, who died by suicide in 1995 at the age of 57, reflected on the changes in the sport during his years as an MLB umpire, from 1969 to 1979.

“When I started, it was played by nine tough competitors on grass, in graceful ballparks,” he wrote. “But while I was busy trying to answer the daily Quiz-O-Gram on the exploding scoreboard … a revolution was taking place around me. By the time I hung up my whisk brush there were ten men on each side, the game was played indoors, on plastic, and I had to spend half my time watching out for a man dressed in a chicken suit who kept trying to kiss me.”

He had no idea what was coming next.