The NBA Couldn’t Stop the Suns From Forming a Superteam

On the eve of the Denver Nuggets and Miami Heat’s matchup in the NBA Finals, the perfect stage for his sermon, commissioner Adam Silver extolled the wonders of parity.

“Whoever wins this year, it’ll be the fifth consecutive year where we have a new team winning,” he said. “When you think about a 30-team league, and it’s not just the fans in those markets but fans increasingly all over the world, you want a league where everyone feels that if the team they are rooting for is well managed and gets a little bit lucky too—that’s necessary—that they can truly compete for championships.”

After his speech, two mid-market teams that had been built from the bottom up, with two selfless stars at the helms of egalitarian offenses, under the watchful eyes of two of the longest-tenured coaches in the NBA, would battle for a ring. The league, perhaps, was entering a new era of equality and roster stability.

“I think this increased parity we’re seeing around the league is fantastic. It’s part by design too,” Silver continued. “Through successive collective bargaining agreements and the one we just negotiated, there’s some new provisions in that one as well that we hope will help even the playing field to a certain extent.”

The new CBA, which goes into effect in 2023-24, is especially punitive for high-spending teams, particularly those that exceed the second tax apron ($17.5 million above the luxury tax, about $179.5 million total). Some of its provisions, such as those that keep teams above the second apron from consolidating multiple salaries in a trade, seem designed not just to make it harder to form superteams, but to prevent them altogether.

Just two months after the new CBA became public, the Phoenix Suns decided there were merits, in the words of ESPN’s Brian Windhorst, to “smashing” the new rules to bits.

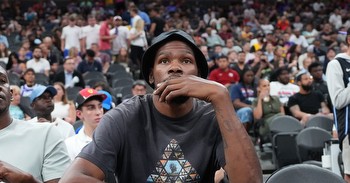

Since Mat Ishbia bought the team in December, the Suns have faced a crossroads between continuity and star chasing twice and have chosen the latter each time. They traded Mikal Bridges and Cam Johnson for Kevin Durant before the trade deadline, and now they’ve traded Chris Paul and Landry Shamet for Bradley Beal and his four-year, $208 million deal. They canned Monty Williams, the architect of the no-nonsense culture that Devin Booker craved but couldn’t build on his own. In the aftermath of the Beal deal, Deandre Ayton (a perpetual trade candidate) and Booker are the only players under contract who remain from the Suns’ Finals run just three years ago.

The Suns now have $161.5 million locked up among Durant, Booker, Beal, and Ayton. In 2025-26, their collective salary jumps will amount to $199 million. Even if they deal Ayton, it’s hard to envision a version of this team that won’t be above the second apron for multiple years.

That means, among other things, that the Suns won’t be able to sign bought-out players, aggregate salaries into a trade, send out cash in deals, use their non-taxpayer midlevel exception, or trade their first-round picks for seven years. If they’re above the apron for the next five years, that pick will drop to the bottom of the draft. Defying the league’s new rules is an incrediblyhigh-riskproposition: If the Suns don’t win a championship, imagine how it’ll feel if a rebuilding Phoenix team ends up drafting at 30th eight years from now. Good thing the Suns don’t care about the draft anyway. Plus, when your CEO’s dad is an agent, building your team through trades is just leaning into your strengths.

Superteams, for most of NBA history, have been expensive and difficult to build, but the story remains the same: If you have free-spending ownership and a magnetic superstar, then imagination, ingenuity, and a certain tolerance for recklessness can help make anything happen.

The Suns have surrendered historic levels of roster flexibility to compile the Durant-Booker-Beal trio, but one thing they can do is re-sign Torrey Craig, Cam Payne, and the hodgepodge of role players they have Bird rights to. They can also potentially use those players’ salaries in one-to-one trades, revealing a potential loophole in the new CBA that other high spenders could also use.

I don’t know how much “fuck it, we ball” energy Joe Lacob has left in him, but if the Warriors are looking to upgrade and the owner can stomach more exorbitant luxury tax bills, Klay Thompson’s expiring $43 million contract would become a fascinating piece of trade bait. After the new rules kick in, the Warriors, despite having $211 million on the books next season, could still trade Thompson for a superstar making within 110 percent of his salary.

A team that has the draft capital to juice an offer could use this strategy to put together a reasonable package for a disgruntled star, especially if the alternative is letting them walk for nothing. For the Heat, Kyle Lowry’s expiring contract ($29.6 million) could essentially serve as a trade exception that allows them to absorb a star.

The Celtics have been worried about giving Jaylen Brown a massive contract, but maybe they shouldn’t sweat it as much: One day, they might be able to trade for Giannis Antetokounmpo using Brown’s contract.

The Clippers, owned by Steve Ballmer, the only person in the league for whom luxury tax bills are true chump change, could follow a similar path. Los Angeles can’t consolidate its many reasonably paid role players for a superstar anymore, but it could use the salaries of its older players to make rotational upgrades. Marcus Morris’s expiring $17 million contract could be attractive to a team looking for cap relief. Same for Eric Gordon’s deal.

Any team that decides to go down this path will be flouting everything the league is trying to encourage: long-term development through the draft and less player movement through trades. It reminds me of when the NBA decided not to call shooting fouls on defenders covering a rip-through move. Eventually, cagey rule manipulators like Paul learned to circumvent the change and saved the move for when their teams were in the penalty and needed a call the most. The rule change limited, but didn’t eliminate, the move.

The same thing could happen here. The Suns laid out a new intrepid, expensive blueprint. Twelve months from now, if they’re hoisting the Larry O’Brien Trophy, just weeks before the CBA’s new second apron rules kick in, it’ll be clear that the CBA’s ramifications are nothing but a porous deterrent. But success is far from guaranteed. In fact, the Suns’ title odds jumped from plus-800 to only plus-650 after the trade.

Sift through NBA history, and you’ll realize that the configuration most likely to win multiple championships is the one we just witnessed earlier this month: a generational superstar and a reliable complementary second star surrounded by a bevy of well-fitting role players. This has been the natural order for most locker rooms and cap sheets. Kobe and Shaq. Bird and McHale. Magic and Kareem. Jordan and Pippen. Jokic and Jamal.

The reason? Superteams are hard to construct and harder to keep together, and they come with inherent structural risks. They’re top heavy and filled out with minimum-salary players, counterintuitively requiring the stars to take on an even greater burden. This transforms their roles and makes them perform the dirty work that’s usually reserved for lesser players. As a result, injuries can be borderline catastrophic.

There have been exceptions, like the Heatles and the Durant-era Warriors. Miami pulled off its Big Three because Chris Bosh transformed into a floor-stretching defensive linchpin while LeBron, in a way only he could, absorbed every other responsibility, from scoring to playmaking to rebounding to guarding the opposition’s best player to filling the positional hole of the moment. He also missed a total of just 18 games in four years.

In contrast, Beal and Durant have missed 111 and 171 games, respectively, in the last four seasons. Collectively, Phoenix’s new Big Three has missed a staggering 321 games over the last four seasons.

Durant, 34, has played 42,906 minutes (including in the postseason) in his 15-year career. He is also the most versatile and the best rim protector and rebounder of the three—the best equipped to make the kind of transformation that has allowed previous superteams to thrive. In his first two seasons with the Warriors, he blocked nearly 1.7 shots per game, protecting the rim for stretches when Draymond Green was unavailable. He discovered and leaned into his versatility, perhaps because he was no longer required to score all the time.

There is a version of the Suns that mimics the chart-busting early days of the Kyrie Irving–KD–James Harden Nets, but the fate of that team points to more omens than reasons to believe. Durant has now been a part of so many hastily constructed superteams that the decision to go all in on another feels more like a cautionary tale than an imposing threat for the rest of the league. As soon as the Suns brought Durant on, the jokes that he was joining another superteam started flying. The irony is that when Durant tries to follow an “easier” path, he ends up bearing a larger burden.

Since leaving the Warriors, he has carried an enormous load in three straight postseasons because his superteam teammates have been unavailable. In 2021, he was without Kyrie and Harden at different junctures. In 2022, it was Ben Simmons. This year, it was Paul.

The responsibility has led to some incredible performances from Durant—his 49-point triple-double will go down as one of the best, most inspiring performances in a loss in NBA history—but eventually, it becomes too much to shoulder.

Would Phoenix—the only team that pushed the Nuggets to six games this postseason—have been better off just tinkering and running it back? Maybe a full season with Durant, Paul in his new role, and the addition of a reliable, physical backup big man would have delivered this team to the promised land.

But recent Suns history tells us that wouldn’t have guaranteed anything either. After losing in the 2021 Finals, the Suns chose continuity, bolstering their frontcourt depth and pouring into the development of Bridges and Johnson. They won a franchise-record 64 games the following season only to lose in embarrassing fashion to the Mavericks in a second-round Game 7. The next year, those guys got shipped out for one of the greatest scorers of all time, and the result was another embarrassing elimination in the second round.

The only real answer to team building is that there are no answers. There’s no tried-and-true formula for winning, no configuration that is destined to fail. In the end, an on-paper superteam doesn’t amount to anything. Success comes down to what happens between the four lines of the court.