The Rogers twins reunite in the Giants bullpen and their parents couldn’t be happier

The drive from Fort Collins back to Littleton was a straight shot down I-25. And it was dead quiet.

Chatfield High’s baseball team got smoked 8-0 in the first round of the Colorado Class 5A playoffs. Taylor Rogers started the game and took the loss. His identical twin, Tyler, never left the bench. Their senior season was over. Something bigger than that was ending, too.

The two brothers had done everything together, even if sometimes it felt like baseball didn’t leave time for much else. They were teammates at every stop, of course, starting with T-ball in the South Jeffco Sports Association, when they were so much better than the other kids that their coach considered not playing both of them at the same time. Little League came next. They took turns pitching for the Coyotes. Taylor, a left-handed thrower, also played first base. Tyler, who used a fork and pencil with his left hand but felt more natural throwing right-handed, played second and third.

GO DEEPER

Mirror men: You can't tell identical twins Taylor and Tyler Rogers apart — until you see them throw

Scott Rogers, a fourth-generation firefighter who retired this January following a 35-year career, laughs when he remembers how heads would turn whenever he pulled up to the Little League ballpark in his fire engine, hoping to see both his sons collect a hit or two before the next call came in. He won’t ever forget the time Taylor whirled on the mound and Tyler tagged out a stunned runner leaning off second base.

“It was against an All-Star team from Utah,” Scott Rogers said in a recent phone interview. “Their coach said it was the best pickoff play he’d ever seen. And it wasn’t something they practiced. They just knew what the other was thinking. Just telepathically, they got it done.”

Family vacations revolved around baseball, too. Their mother, Amy, would hitch up the fifth-wheel trailer for Omaha or St. Louis or wherever the boys’ team happened to have a tournament. Other kids would be holed up in motel rooms playing video games. Tyler and Taylor would be at the campground riding bikes or swimming or baiting hooks with Grandpa. When they weren’t playing catch, anyway.

They were almost always playing catch. The only companion who successfully competed for their attention was their golden retriever, Champ, who had telepathic powers of his own. Champ would paw at the screen door just as the boys were about to grab their gloves.

“He followed them everywhere,” Amy Rogers said. “They were always outside throwing the baseball together. And Champ was always there. They must’ve been 25 or 26 years old when we had to put him down. They cried like little boys.”

When Taylor and Tyler got to high school, they played on the freshman football team before leaving the sport behind — other than the occasional rule-breaking spirals they still throw to each other in their mom’s living room. Taylor also displayed talent on the basketball court.

But they were a baseball family first.

“Oh, I would do it all again,” Amy Rogers said. “Learning the game, refining their skills and talents, always being there to support each other — we were a close-knit team.”

Then came that final loss in Fort Collins. After all the campgrounds and catch play and connectivity, the twins were headed down separate paths — Taylor to the University of Kentucky on a Division I scholarship, Tyler to Garden City Community College in Kansas where he’d study fire science and see if the baseball team might have a place for him.

They wouldn’t be teammates. Instead, they would become each other’s biggest fan.

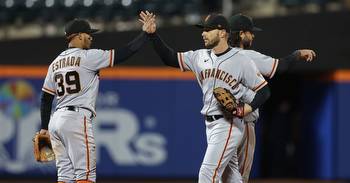

Now 14 years later, beyond their most audacious dreams, and after following very different roads to the major leagues, they get to be both.

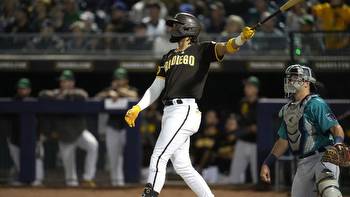

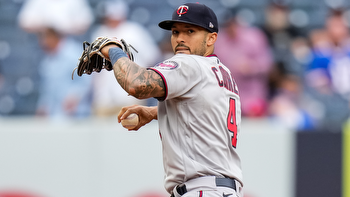

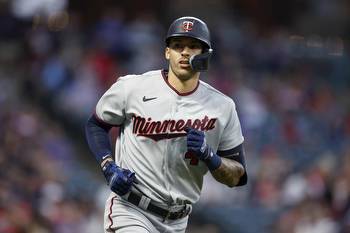

Taylor Rogers arrived at Scottsdale Stadium last week and began buttoning up a San Francisco Giants practice jersey for the first time after signing a three-year, $33 million contract. Tyler Rogers, a prominent member of the Giants bullpen each of the past three seasons, is his nearest locker mate.

It was cool enough when Tyler’s debut in 2019 made them the 10th set of twins to play in the major leagues. It was cooler still last April when they became just the fifth set of twins to pitch in the same game — something they never did as high school teammates. They won’t forget the pinch-me thrill of playing catch on a big-league field for the first time last season in San Diego, after Taylor had been traded by the Twins to the Padres.

But this? Becoming the fourth twin brothers to become major-league teammates, and the first since Ozzie and Jose Canseco briefly appeared together with the 1990 A’s? The odds of that happening seemed too remote to entertain, even after they both established themselves as big-league relievers.

It’s finally starting to sink in.

“It didn’t really hit me until I was in here putting on Giants stuff,” Taylor Rogers said. “Then it’s, ‘Like, OK, this is really happening.'”

The Rogers brothers are teammates again. With Ritz-Carltons instead of campgrounds.

Giants right-hander John Brebbia wanted to be prepared. He punched up Google image searches on both Rogers brothers and blew up their head shots. He scanned for a freckle here, an earlobe there. He settled on the hair. Tyler keeps it a bit more closely cropped up top. Brebbia was confident he wouldn’t make an idiot of himself.

“Then I get to the clubhouse and the first time one of ’em walks past me, I’m like, ‘Uhhh…Tyyyyler?'” Brebbia said with a cringe and an eyeroll. “Wrong!”

That’s life when you share space with an identical twin. You get used to the stares and the confused expressions, even if they still test your patience every now and again. You come to terms with having to humor people. You try to remind yourself that they aren’t reducing you to a novelty act, even if that’s how it comes across sometimes. Stupid as it seems, it’s easy for folks to forget that you are separate people.

Amy Rogers understood from the beginning that part of raising identical twins was encouraging them to discover their own identities. So she didn’t dress them in matching outfits. She didn’t fret if one of them got a new bat one year and the other didn’t. “Just because you guys are the same size, age, gender, it doesn’t mean you’ll get everything at the same time,” she’d tell them after a visit to the sporting goods store. “If we go to the doctor and your brother gets a shot, does that mean you want a shot?”

But when one of them got a new bat, they’d gush with gratitude.

“It was, ‘Thank you, mom, I’ll hit a home run for you today,'” Amy Rogers said. “It was very cute. I have a lot of baseballs that are signed, To Mom, happy Mother’s Day.”

It was important to create windows when her sons wouldn’t be together. Even something as small as breaking up their commute to school made a difference. After the boys learned to drive, they shared a white Toyota T-100 truck. Then their grandfather gave them a second car prior to their senior year. Taylor got the Jeep Wrangler. Tyler kept the truck, which was just fine with him.

“When you’re never on your own time, it gets old after a while,” Tyler said. “Every morning he’s either waiting on you or you’re waiting on him.”

Full disclosure: it was usually the former.

“I guess I’d put it this way: I like to be early to things,” Tyler said. “And Taylor likes to be super early to things.”

Their personalities are not nearly as identical as their profiles. They might have indistinct voices and similar mannerisms, but their parents will tell you that Tyler is a little quicker with a joke. He’s got more of a sarcastic streak. Taylor tends to be a little more reserved.

“But in character and values and integrity, they are the same,” Amy Rogers said. “They exhibit those excellent behaviors 100 percent. I think players will really enjoy being around them. It’s funny how they’ll get to laughing and nobody else understands what the jokes are. They’ll be belly laughing and nobody knows what’s going on.”

They probably both picked up attributes from their father, who pulled his last 48-hour overtime shift as a battalion chief with West Metro Fire just a few weeks before his ringing-out ceremony in January. He received a commemorative axe and was saluted by the entire department. It was an emotional afternoon. He hadn’t realized how important his mentorship was to younger firefighters until they spoke at the ceremony. Tyler and Taylor both said a few words, too.

“I’ve always been impressed with their work ethic in baseball,” Scott Rogers said. “They said they got that from me, which was very, very moving. I’m glad, because at least they got something. They certainly didn’t get their athletic talent from me.”

No surprise: Tyler isn’t the only one with a sarcastic streak.

“One of the reasons I retired when I did was because it was hard to get to their games,” Scott Rogers said. “So as soon as I do, they end up on the same team.”

But first they had more than a decade on their own. Amy Rogers is grateful that it worked out that way.

“I’m just really happy for them to be experiencing this together as adults,” she said. “It could be a burden for them to always be together, always have people confused and asking which one you are. So it was good to have some separation time. It was good for them to be on their own and learn how to be a good teammate.”

They weren’t always together, though. There was one year in high school when they didn’t play baseball on the same team. As Taylor thought back on his junior year, it dawned on him: that was the time when his brother proved to be the best teammate of all.

Both Rogers brothers were late bloomers but Taylor’s abilities began to stand out by the time they were juniors. He threw in the low 90s. He made varsity for the first time. Tyler did not, and even quit baseball for a while.

“At the time, I wasn’t getting to play,” Tyler said. “It was one of those teenage things. You try to figure it out. Luckily, I got to play again. But at the time, he was all-state and I was sitting on JV. I mean, he was arguably better than anyone in the state. What was I supposed to do? Get mad at that? I was happy for him and supportive of him.”

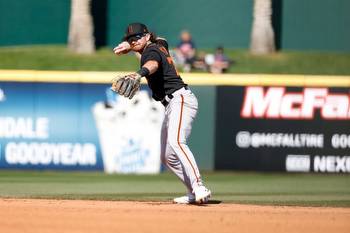

They were teammates again on varsity as seniors. Taylor, wearing No. 21, struck out 69 in 42 innings and was getting interest from pro scouts and college programs. Tyler, wearing No. 20, pitched in just four games. He didn’t throw hard, he had a 7.54 ERA and he walked 12 in 13 innings — the definition of a non-prospect. But when he got to Garden City CC, there wasn’t much more to do than read about fire behavior and arson investigation. So he tried out for the baseball team. That’s when his coach, Chris Finnegan, suggested the submarine-style delivery that would put him on a path to Austin Peay State University and then to pro ball as a 10th-round pick.

At the time, though, Taylor was thriving at Kentucky. He was doing things like earning the win in the 2011 Cape Cod League All-Star Game at Fenway Park. And Tyler was a second-team All-Kansas Jayhawk Community College Conference selection.

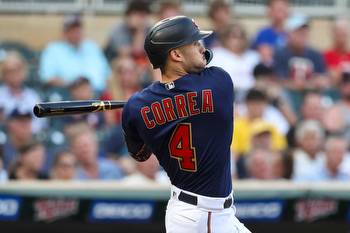

“I got drafted out of high school and people would say to Ty, ‘Why didn’t you?'” Taylor said. “I’m going to Division I and he’s going to JUCO and he hears, ‘Why aren’t you going to Kentucky too?’ I get called up first (by the Minnesota Twins in 2016) and he’s stuck at (Triple-A) Sacramento and everyone’s like, ‘When are you getting called up?’ So he had to deal with that for a long period of time.

“He’s the one who started being a support system to me instead of letting it become a jealousy thing. He could’ve gone a whole different direction. But he was on JV and he still played catch with me, made sure I was ready even when he wasn’t playing. At the time, I realized it. But after the fact, into college and pro ball, I really thought, ‘Wow. He handled that really well.'”

Tyler’s support made it easy for Taylor to celebrate his success and not waste brain space feeling guilty or awkward about it. It’s also why Taylor had reservations this past offseason about signing with the Giants when he started to narrow his list of potential teams in free agency. He called his father for advice.

“Tay, this is your free agency,” Scott Rogers told him. “This is where you can make it or break it. I know you’re concerned that the Giants are Ty’s world, not yours. I know you don’t want to infringe on him or come in as the more seasoned reliever. But this is about you, not your brother.”

It was a version of the line Scott Rogers would often recite to his sons while they were growing up: “Chase your passion and your pension.”

Tyler was careful not to influence his brother either way. He also wanted to respect Taylor’s process and support whatever he decided was best for him and his career. But when Taylor asked his brother about the Giants, all concerns evaporated.

“That would be so awesome!” Tyler told him. “Let’s focus on your free agency. And if it happens, it happens.”

The Giants didn’t offer Taylor $33 million because they wanted to toss their beat writers a nice narrative. They needed a durable and dependable late-inning lefty to bolster a bullpen that failed to sustain its success from 2021 and they had Taylor at the top of their board. They valued his end-of-game experience as they sought to lighten the load on talented young closer Camilo Doval, who made a few too many appearances for their comfort last season.

Tyler is coming off a season with more batted-ball noise, but the Giants remain confident that his combination of movement and unique attack angle will make him one of the better relievers in the league again. A move to the balanced schedule, in which the Giants will play just 12 games (down from 19) against NL West teams and will see every AL team at least once, figures to be a big-time advantage for an unconventional reliever like Tyler who tends to thrive on unfamiliarity.

Tyler Rogers definitely uses that unfamiliarity to his advantage — even if that isn’t the first attribute that comes to mind when you have an identical twin sharing the same space again.

“We had our time to have our own identities, our own careers,” Taylor Rogers said. “In college, I was just Taylor there. You start to grow a little more when you don’t have someone by your side through everything. You start to become more of an individual. I’m not sure other people would understand that, but it was nice just to be your own person.

“That’s why this is perfect timing. I feel like we did that long enough, we’re older, we’re hopefully adult-ish enough now that hopefully that shouldn’t come into play anymore.”

Maybe adult-ish is the best way to describe it.

“Is it true,” said Tyler, crashing his brother’s introductory teleconference call with reporters, “that the Giants have the best-looking bullpen in the National League?”