‘Why not me?’ A first-time announcer, racing toward history, finds her stride

BENSALEM, Pa. — Her feet anchored by her Converse sneakers, Jessica Paquette stands in front of a spread of windows. Binoculars pressed to her eyes with one hand, she puts the other on her hip, flips a switch on the board in front of her, and starts talking. “And now they’re all in,’’ she begins. “Off and racing. An uneventful start here with some speed out of the gate.’’ It is a sun-splashed spring Monday at Parx Racing in suburban Philadelphia. A few people — no more than a hundred — sit on the concrete benches near the finish line, or lean on the rail as the horses break from the gate in the second race of the day.

Rejected Again, a 6-year-old colt with 5-2 odds, gets space early and cruises to the finish line, his entire trip narrated by Paquette from her perch high atop the track.

Sixty-one years ago, a radio personality who went by Jacqueline the Kitten (to her husband’s Jack the Cat) on the air, took over her husband’s other job, becoming the track announcer at Jefferson Downs racetrack in Louisiana. Described in one news clip as a “vivacious blonde” who dressed like a fashion model and wore French perfume, Ann Elliott called horse races for four years, from 1962 to 1966. In the six decades since, Angela Hermann pinch-hit to finish out a season at Golden Gate Fields in 2016, and Dani Jackson has done guest calls in both her native England and at Turf Paradise in Arizona.

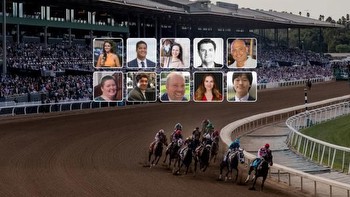

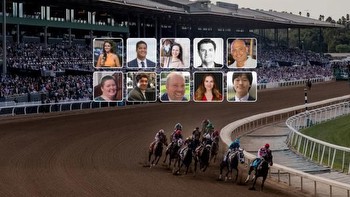

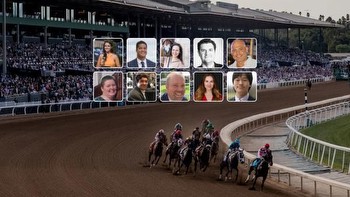

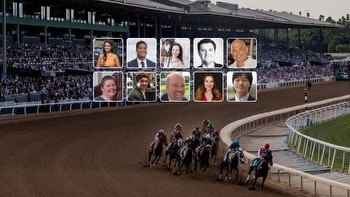

Until Parx hired Paquette in September 2022, no woman had been given the mic as a full-time track announcer since Elliott. Come September 2023, when Parx hosts the Pennsylvania Derby, Paquette will become the first woman to call a Grade 1 stakes race. Typical of a pioneer and groundbreaker, Paquette has not exactly enjoyed an easy ride.

Were she to call her own race, she might describe one with a tough break out of the gate, followed by a clog of congestion in front of her. Many a day Paquette found herself alone in the booth, gulping back tears, either frustrated by her own quest for perfection or defeated by the cruel criticism lobbed at her by fans and even her peers.

But recently a clearer path has opened for her on the backstretch. Paquette has found her stride, her voice and her rhythm, and while she still has her share of detractors, she no longer lets them block her view of the finish line.

“Why do this? Why not?” Paquette says. “I thought deep down I could get the skill set down, and I knew no one would work harder than me. But more than that, I got where I got because women took the arrows for me. This was my chance to show a little girl somewhere that she can have her own microphone and do this, with an easier path than I had.’’

Upon settling in to call her first race at Parx nine months ago, Paquette had announced exactly one thoroughbred race, and that was in 2014. She was hardly a racing novice. Paquette worked as a handicapper and paddock analyst for years, but her only race calling experience was with quarter horses, which is basically like calling a sprint.

Thoroughbred announcing is incredibly difficult — even veteran play-by-play announcers bristle when they think about the gig. The animals move fast and stick close together, identifiable by only their saddle cloth or jockey silks. Paquette keeps a lineup of colored pencils in the booth to mark up her race sheets with the proper silks, and scratches notes next to each horse’s name — for example, if it’s wearing blinkers or not — to fill in the details as she calls 10 races a day three days a week. As they hit the backstretch, they’re nearly impossible to discern by the naked eye — and that’s without factoring in the elements, such as rain or fog. Meanwhile, anxious bettors hang on the announcer’s every word.

“You memorize the field, get dialed in and then you’ve got to forget the names you just remembered five minutes ago,’’ says Chris Griffin, her predecessor at Parx. “It’s not something you can go to school for. They’re not talking about what to say when a horse stumbled out of the gate in the fifth race at journalism school.”

Most people get their reps at smaller venues, finding their voice and their rhythm in relative obscurity. Griffin, for example, started as a play-by-play announcer for the National Hot Rod Association and with the Harlem Globetrotters. The first horse race he called was at California’s Humboldt County Fair. Jason Beem, one of Paquette’s closest friends, started at River Downs in Cincinnati. Parx is not to be confused with Churchill Downs, but it is a deeper end of the pool by comparison. “And they didn’t even give me swimmies,’’ Paquette jokes, “let alone a life jacket.’’

Humor is Paquette’s armor. Her go-to for hurtful criticism is sarcastic deflection, where she whips a zinger with a smile even if it doesn’t quite reach her eyes. This has not been easy. It has even, at times, been cruel. The crying in the booth is not dramatic hyperbole. Many a day, Paquette wiped away the tears before she put the binoculars back up to call another race.

She has learned, as many women in male-dominated fields do, to pick her battles, to figure out when to fight back and when to walk away. The mute and block buttons are good Twitter friends. She chooses grace as often as she can. It is, however, exhausting. “I knew people would be kind of horrible,’’ she says. “And they’ve surpassed my expectations.’’

Just caught the tenth. Is Jessica related to Stuttering John?

I don’t know why anyone would want to publicly embarrass themselves.

It’s the way of current society. Qualified, competent or not, being in a rush to be the first to hire a woman, transgender, openly gay, or person of color.

I go to the track to get away from my old lady’s voice.

The 4th reminded me of when the Mets have a kid come on to announce an inning of a game because he won a contest. But usually the kid practices before going on.

Glad you’re enjoying yourself. Stevie Wonder could do a better job.

That’s just a dose of the vitriol tossed Paquette’s way via message boards and social media. Others pretend to offer advice, all while prefacing their remarks with “love’’ or “honey.’’ Some intimated about just how she got the job; some flat-out propositioned her.

Those hurt. What truly stung were people inside the industry who snidely suggested she take fewer selfies (“as if I’m asking for it,’’ Paquette says), or whispered behind her back about what a joke she was. One fellow track announcer — whom Paquette declines to name — went so far as to send her a packet for a camp he runs for kids aspiring to get into the field. At first she thought maybe he wanted her to speak to the campers. “Oh, no,’’ she says. “He thought I should join the 12-year-old boy who wants to try this. I sat there fuming for a second, but then I convinced myself he’s just being kind. Say thank you. It’s just easier to survive that way.’’

Paquette is the first to admit she was not very good when she started. She struggled to identify leading horses, sometimes until late in the race, stumbled over names, paused for long breaks, and stopped and started. She didn’t have a catchphrase, so she borrowed familiar ones — until Beem told her that “and down the stretch they come” is trademarked by Dave Johnson and that he had previously sued for infringement.

None of this caught her bosses at Parx by surprise. They hired her because they respected her knowledge. Paquette kids that she is like a “horse ‘Rain Man,’” learning their nuances and running styles, becoming so familiar with them she can tell in the paddock if they’re having a good day or a bad day. She had worked at Parx during the Pennsylvania Derby, and the administrators there saw firsthand that she knew what she was talking about.

They also liked that she understood that the track announcer’s job extended beyond a race call. With her paddock analyst skills, Paquette could do interviews for the track site and offer handicapping tips. Griffin also changed things at Parx, using his burgeoning social media to bring life to the world behind the scenes and drum up interest in live racing. Paquette, who has 11,000 Twitter followers, could do that, too. “This is not and never was an experiment,’’ says Rich Romano, Parx director of operations. “And it’s not a PR move. Did we get attention because of her? Are you writing an article because of her? Yes. But we believed in Jess and what she could do. She’s a spitfire, or like a hummingbird. She just goes. She doesn’t back down. She works. That’s why this works.’’

Why it works for Parx makes some business sense. What is harder to comprehend — why would Paquette do this to herself?

She’s an achiever — a type A-plus, she jokes. That’s part of it. By way of example: On Oct. 1, 2021, Paquette, who shows horses, was riding a young horse she was thinking about buying when a truck backfired. The horse tossed her. She broke her back — “exploded my L4,’’ is how she describes it — necessitating spinal surgery and four months in a confining back brace, the sort where she couldn’t shower herself or put on her own socks.

On Oct. 7, 2022 — 371 days after the horse threw her — she ran in the Chicago Marathon. This year, 18 months after breaking her back, she ran the Boston Marathon. She finished in 4:30.25. The next morning she was at her station in the booth at Parx. “Constant movement keeps me at my best,’’ says the 38-year-old Paquette. “I don’t decompress.’’

But she’s also a person with a singular deep and abiding lifelong passion. “You know how every grade has that weird horsy girl?” she says. “That was me.’’ Paquette grew up in Lowell, Mass., in a family that had zero background or interest in horses, and even less money to get into the sport. For whatever reason — she still can’t really explain it — the animals struck a nerve with Paquette. She recognized it was out of her reach, so she sought to craft a horse-centric world for herself. She found kindred spirits on AOL message boards, where other teens would bond over their love of horses, even creating fan clubs for their favorite equine athletes.

Paquette figured her horse experiences would never extend beyond the reach of her keyboard. Until Trudy McCaffery, a West Coast-based thoroughbred breeder and owner, got wind of the kids’ devotion and started a non-profit called Kids to the Cup.

Designed to spark interest in horse racing, the program brought kids to major races. At 14, Paquette hopped a flight to Florida with her parents to attend the Breeders’ Cup at Gulfstream Park, the whole thing paid for by Kids to the Cup. They visited the horses, met with the jockeys, toured the announcer’s booth and chatted with the trainers. “You know when you’re a weird teenager with a really niche passion, you’re not exactly winning popularity contests,’’ Paquette says. “We felt like we found ourselves and our people. None of us were born into horse racing, and it’s a real nepotism industry. This was the only way we’d get a foot in the door.’’

Her foot wedged in, there was no way Paquette was backing out. As soon as she got her license, she started driving to nearby Rockingham Park, getting up before dawn to work as a hot walker. After school, she’d go back to pick the brains of the older horsemen and handful of horsewomen around the track. Lynne Snierson, the track’s director of communications, took the teenager under her wing. “She was tough and brilliant, and taught me how to not be afraid of being a woman,’’ Paquette says. “She did it all with grace, a sense of humor, and great hair and makeup.’’

Once Paquette turned 18, she got a job as a mutuel clerk at Suffolk Downs in Boston, turning that into an internship in the marketing and communications department while she worked on a journalism degree at nearby Rivier College in New Hampshire.

She had no real interest in being on camera or in front of a microphone, but then one day someone failed to show up at work, and Paquette took over as a paddock analyst. What she didn’t know about TV she made up for with her knowledge of horses. “The approach I try to take with opportunities, especially as I’ve got older, is to say, why not me?” Paquette says. “It’s really easy to talk yourself out of something. It’s better to talk yourself into it.’’ Paquette spent 20 years at Suffolk Downs, eventually becoming the track’s vice president of marketing, and in 2014 called her first race, pinch-hitting when a freak Boston-area tornado delayed their full-time announcer’s arrival to work.

The historic track halted live racing in 2019, and Paquette sought out other jobs in horse racing. She worked for the Thoroughbred Retirement Foundation in communications, and as a paddock analyst at both Sam Houston in Texas and Colonial Downs in Virginia, commuting from her home in Boston. In Texas, she started calling quarter horse races.

When Griffin decided to leave Parx for Aqueduct and Monmouth, she decided to reach out. She was not thinking about breaking a gender barrier; she merely wanted to stay in horse racing. “We had no delusions. We did not expect Jess to come in here and be Tom Durkin,’’ Romano says of NBC’s legendary announcer. “We also didn’t realize how vicious people could be. But she has weathered it like a pro.’’

Somewhere around her third week on the job, even Paquette’s closest friends wondered if she could and would stick it out. Beem fielded regular calls as Paquette dealt with the blowback and her own self scrutiny. She anguished over her struggles and mistakes, and though she knew it wasn’t healthy, couldn’t stop reading her Twitter mentions or cruising the message boards to hear from her critics.

She practiced, pretending to call televised races at home while her accountant husband worked. She sent her replays to Beem and Griffin. Both offered input, but tried to keep the advice to the minimum. “I just harped on the reps,’’ Beem says. “She didn’t need more advice. She had too many people offering that as it was. She had to find her own voice, but you can only do that by doing it.’’

There was no moment, no perfect race where it all coalesced, but with time and experience she has improved. Her delivery is smooth and deliberate. Once worried that, as a woman, she’d be accused of sounding shrill if she brought excitement into her voice, she has allowed herself to enjoy the anticipation of a race as she calls it — and even find room to laugh at the absurdity life occasionally likes to toss at her. “There’s a horse named Somebody,’’ she says. “So there I am saying, ‘Somebody is in the lead.’ That went well.’’

The trolls still exist; “Oh honey you need all the help you can get,” one responded via Twitter on May 23, but they have been drowned out by a more steady drumbeat of supporters. “You can call a race you are very good and talented your gender is irrelevant you Rock as a race caller,’’ another chimed in on May 25. “It’s honestly a lesson for any woman in any career path,’’ she says. “Whether you’re doing this, or you’re a doctor or a scientist, it’s gonna suck for a while. It’s just gonna suck. It shouldn’t, but it will. You just have to get through it.’’

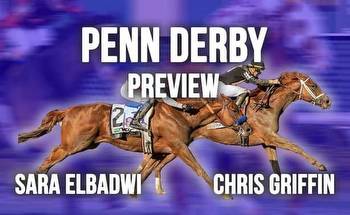

Paquette has not circled the calendar, but she knows the big day is coming — Sept. 23. The Pennsylvania Derby has become a sought-after race for name-brand horses and trainers thanks largely to its well-timed placement on the racing calendar, as a lead-up to the Breeders’ Cup and its $1 million purse. Last year, Bob Baffert’s Taiba won, and the year before, Hot Rod Charlie, who finished third in the Kentucky Derby and second in the Belmont, crossed the finish line first.

While everyone eagerly awaits the last race of the day, when the colts load into the starting gate, the day’s biggest moment will come in the race just before the Derby. That’s when Paquette will become the first woman in history to call a G1 race. Fittingly, history will arrive with the running of the Pennsylvania Cotillion — a race for fillies.