A's finances: In the red, the black, or singing the blues in pursuit of a new stadium?

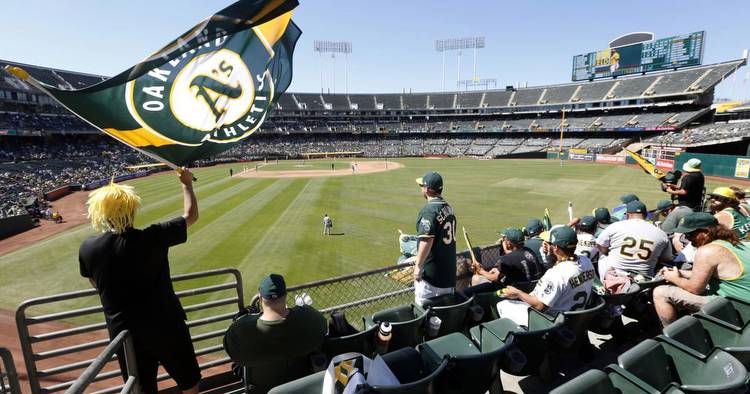

The last three games at the Coliseum drew 3,035, 3,407 and 4,930 fans. Sometimes the only sound echoing through the massive concrete structure came from a few drummers in the stands.

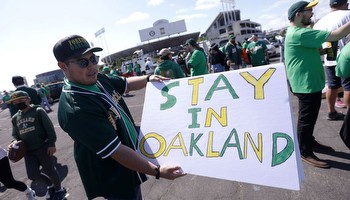

They were rallying in support of their Oakland Athletics, but perhaps the message could have been more of a demonstration against an ownership that is pushing for a relocation to Las Vegas.

In paying their players $57.795 million, the A's have MLB's smallest payroll and are destined to have the lowest attendance. The troubling circumstances at 7000 Coliseum Way make it easier for owner John Fisher to orchestrate an exit from Oakland.

It would have been entirely understandable if those fans were beating the drum for the A's to stay.

The official organizational line is that nothing will change unless the A's get a new stadium to generate enough revenue for them to regularly contend. The organization advances that claim despite just four MLB teams reaching the playoffs more than the small-budget A's since 2000.

Like most other MLB teams, the A's haven't been fully transparent about their revenue streams, but they shared financial information in a statement to The Chronicle while disputing a recent assessment by Forbes that the team made $29 million last year in operating income.

In their statement, the A's claim they actually lost approximately $9 million "in cash basis" in 2022 as part of $175 million in losses over the past six years.

Because most baseball teams don't open their books — the Braves and Blue Jays being the exceptions because they're publicly traded companies — the A's actual finances aren't known. Though players' salaries are made public, owners' revenues and expenses are closely guarded secrets.

"There could be some intentionally fuzzy math going on," said David Carter, USC sports-business professor and founder of the Sports Business Group. "Team owners don't really want an accurate snapshot of their business going public.

"A second part of that is, teams don't want their numbers out there because of the union. When it comes to negotiating labor agreements, owners would prefer the union not have that information."

It's clear the A's generate less revenue than the San Francisco Giants, in part because the Giants have a destination ballpark they own and can charge a premium for tickets that fans have been willing to pay, and the A's don't. Commissioner Rob Manfred echoed the A's claims in a New York Post podcast last week, saying, "That club lost money last year," disputing the Forbes report that the A's made a profit. "We don't give them our numbers," Manfred said, "They're not public. I understand why they (Forbes) make that mistake."

Manfred is employed by the A's and MLB's other team owners.

Both Forbes and the website Sportico examine teams' finances and list them accordingly, and stand by their numbers while disclosing that, though their research is extensive, they sometimes make educated guesses. Nevertheless, their A's estimates are somewhat similar.

Forbes reports that the A's are worth $1.18 billion, lower than every MLB team but the Marlins. Sportico's figure is $1.31 billion, ranking ahead of four other teams.

Forbes estimated the A's revenue last year was $212 million, Sportico $205 million; Forbes calculated Oakland's $29 million in operating income by subtracting operating expenses from the perceived $212 million in revenues.

However, the A's told The Chronicle both outlets' revenue figures were high and that the actual amount is closer to $190 million. Either way, it would rank last in the majors on both the Forbes and Sportico lists.

"A lot or almost all of that is a function of attendance and premium seating," said Mike Ozanian, who constructed the Forbes report, pointing out the MLB-low 9,849 tickets the A's sold per game last season led to poor numbers in other ballpark revenue, including concessions and merchandise.

Although it's impossible for those outside the organization to know the A's exact revenue breakdown, it's easy to figure what they make in national TV revenue, given reports of MLB's contracts with ESPN ($3.85 billion), Turner ($3.74 billion) and Fox ($5.1 billion), all seven-year deals through 2028 that guarantee $12.69 billion. That amounts to $60 million per team per year.

MLB sends teams checks annually from league media, sponsorships, licensing, legalized sports gambling, etc. Including the ESPN, Turner and Fox deals, it totals $2.8 billion, according to Sportico, or just north of $90 million per team, though MLB keeps some of that for expenses.

Then there's the A's regional sports network, NBC Sports California. Sportico shows the A's making $53 million last year as part of their 25-year RSN contract that runs through 2033. An industry source said it has escalated to closer to $60 million, still not measuring up to other teams in the American League West.

If the A's flee to Las Vegas, it's highly likely they'd get an inferior regional sports network contract. Not just because they'd move from the nation's sixth-biggest media market to the 40th but because cable revenue is taking a hit throughout baseball. The Diamond Sports Group, with broadcast rights to 14 MLB teams through Bally Sports, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy last month. Furthermore, Warner Brothers Discovery is threatening to pull out of its deals with four other teams. MLB is considering the option of taking over telecasts that would air on MLB Network or stream on MLB.TV.

The A's aren't affected for now, but it's safe to say a Las Vegas RSN wouldn't be as lucrative in the current environment. But that would not deter the A's from moving.

"What the A's would get from stadium sponsorships would more than offset any decline in the RSN fees," Ozanian said.

Carter added, "While the future of RSNs appears cloudy at best, the upside in Las Vegas with ticketing and control of venue with the ability to generate money from other events hosted there, there's a lot of other areas where there is financial upside relative to the uncertainty of Oakland."

The A's have many top-end sponsorships — Anheuser-Busch, Chevrolet, Chevron, Coca-Cola, Mechanics Bank, State Farm, Kaiser Permanente, Gilead Sciences and Eva Airways — but deals are negotiated team by team. In certain cases, the A's benefit significantly less than other teams, which reflects the state of their stadium.

As far as ticket revenue, the A's are at the low end because of their weak ticket sales. That goes for revenue for suites, which are sold game-to-game in Oakland compared with other teams that sell their suites seasonally.

"They're at or near the bottom in just about every revenue category," said Kurt Badenhausen, who assembles the Sportico figures. "But they have the double whammy of not getting propped up by the big-market clubs with a big revenue-sharing check."

Last season was the first for the A's getting phased back in as a recipient for revenue sharing, in which money gets distributed from high-revenue to low-revenue teams, theoretically to assist competitive balance.

MLB decided that the A's, though playing in a major market, qualify again because their home is the antiquated Coliseum. In 2022, the A's received 25% of a full share or, according to Forbes, $11 million. The second year, they receive 50%. According to the collective bargaining agreement, the A's would receive 75% and 100% in ensuing years, but only if they secure a ballpark deal by Jan. 15, 2024.

(When the Forbes report was released March 23, the A's operating income was mistakenly listed at $62.2 million because Forbes had counted 100% revenue sharing, which would have ranked the A's in the top five in operating income. Forbes quickly fixed the numbers to reflect the A's receiving 25%, so the $29 million operating income ranks 16th among the clubs.)

Aside from the $175 million the A's claim they've lost in team operations over six years — coinciding with the time they've focused on Howard Terminal — they assert they've spent $100 million over those six years on their pursuit of an Oakland ballpark, including design, permitting, engineering, litigation, city costs and other expenditures. The A's said that $100 million is not counted in the operations losses.

"We felt compelled to correct the record to ensure the true financial situation of the A's is understood," the A's said in the statement. "The A's will continue to make all possible efforts to try to get agreement on a new ballpark in 2023, to strengthen the team in pursuit of more World Series titles."

As for expenses, payroll is the A's biggest payout: $57.795 million according to the Associated Press, the lowest Opening Day payroll in the majors, nearly $300 million less than MLB's highest payroll, belonging to the Mets, $355,436,854. Two Mets pitchers, Max Scherzer and Justin Verlander, are set to make more together than Oakland's entire roster. By $30 million.

The A's paid $1.2 million in 2022 for their Coliseum lease, a 10-year deal that's set to expire after the 2024 season. They get nothing from stadium naming rights, currently branded RingCentral Coliseum.

Another expense is radio. Other clubs have had lucrative deals — including the Giants with KNBR — but the A's pay Bloomberg 960 AM to be on the air. The team focuses on its streaming platform "A's Cast," which streams its content 24/7 including the game broadcast, pregame and postgame shows and podcasts; 960 AM and 14 other stations pick up the game from "A's Cast."

Among other expenditures: the front-office staff, the baseball department including scouts, stadium operations, game-day staff, security, travel, minor-league costs and draft-pick bonuses. Plus, Coliseum improvements (for example, the Treehouse opened in 2018) and upkeep, which the A's said amounted to about $2 million last year.

All teams benefited from MLB's sale of the streaming service BAMTech to Disney late last year, a $900 million transaction that represented roughly a $30 million windfall for each club. Because it was a one-time payment, it wasn't universally included in team operations revenues.

The A's say the more pressing issue is their losses occurring over time because of their stadium, frequently labeled one of the two worst in MLB, along with Tropicana Field, home of the Tampa Bay Rays, who also are seeking a new venue. But the Rays, also dealing with an old ballpark, have been to the playoffs eight times in the past 15 years to the A's six, winning two AL pennants.

The situation contributes to the A's revenue disparity with most other teams, including the cross-bay Giants. The A's say the only way to get on a better footing is by building a ballpark, whether that's in Oakland or Las Vegas.

Meantime, fans will continue to beat the drum.

Reach John Shea: [email protected]; Twitter: @JohnSheaHey

Visit the San Francisco Chronicle at www.sfchronicle.com