Born into slavery, a Kentucky Derby champ became an American superstar

Most Americans think of horse racing only when the Kentucky Derby arrives the first Saturday of May, but at the turn of the 20th century, jockeys were year-round celebrities — on a par with Tom Brady, Simone Biles and Shohei Ohtani as they competed in the nation’s first mass-spectator sport.

And during the roughly 40-year post-Civil War period bound by the start of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, African Americans were among the sport’s biggest superstars. They drew legions of fans, an eager press and fat purses that were unthinkable for the overwhelming majority of Black men at the time.

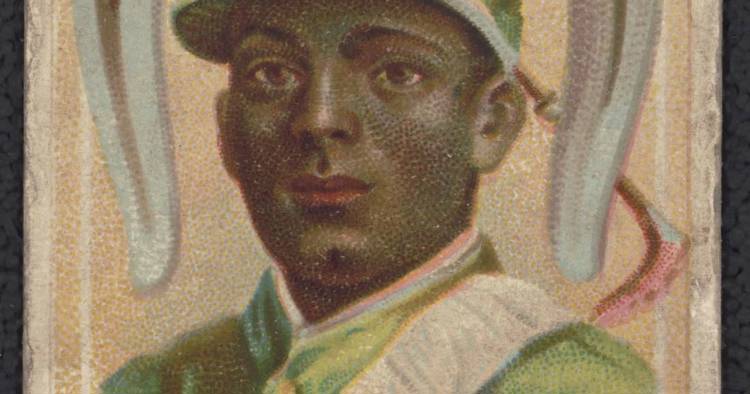

Isaac Murphy, who was born into slavery in 1861 and went on to shatter records and earn millions, outraced almost all of them, Black and white. The first jockey to win the Derby three times, Murphy became a hero to white children, stayed in whites-only hotels and socialized with rich white men, his somber visage gracing pullout posters in racing magazines. A stallion was named in his honor.

Yet Murphy paid a price for his outsize success. And starting just a few years after his early death in 1896, there would be no more Black Derby winners and then, for nearly eight decades, no Black jockeys in the Derby at all. By 2000, when Marlon St. Julien finished seventh atop Curule, the golden age of the Black jockey had largely been forgotten.

Murphy was “one of the first Black superstar athletes,” and his “life encompasses so much about American history at the time,” said Katherine Mooney, a professor of history at Florida State University and author of “Isaac Murphy: The Rise and Fall of the Black Jockey.” Before the advent of the automobile, when Americans were both dependent upon and captivated by horses, Murphy “became a symbol for everybody because racing was so popular,” Mooney said.

African American jockeys — who won 15 of the first 28 Kentucky Derbies — served as a lens into the privileges and limits of Reconstruction as the majority of Black people experienced freedom for the first time. Their lives, Mooney said, began to answer a question: “What would America be like if Black men were heroes?”

A fast ascent, a faster jockeyBy the time Murphy was first thrown from a horse as a teenage stable hand in the 1870s, Black men were a familiar presence in Southern horse racing circles. Before the Civil War, owners of enslaved people flaunted their profits at the track, buying and raising thoroughbreds and asserting their status by brashly risking their money.

And throughout the antebellum South, they often relied on enslaved Black men to perform the physical labor and assume the bodily risk. In horse racing, danger lurked everywhere in the stables and on the track: A kick, a bite or a boot stuck in a stirrup could kill or maim a racing man for life.

Enslavers added dangers of their own. To keep jockeys at riding weight, they were known to force them to sweat the pounds off buried to the neck in manure. A perceived mistake could bring the lash of the whip.

Yet the racing life allowed these enslaved men the freedom to travel and amass expertise and the influence that went along with it — so much so that white men had no choice but to rely on the judgment of Black horsemen.

After Murphy’s father, who escaped slavery and joined the Union army, died during the Civil War, his mother, a formerly enslaved laundress named America, placed her young son under the tutelage of Eli Jordan, a close family friend in Lexington, Ky., and a highly regarded Black horse trainer.

A sliver of a boy, Murphy was a natural prospect for jockeying, and Jordan was quick to shape his talent and seed the next Black racing generation for success. Murphy referred to his mentor as “the old man”; Jordan, in turn, praised Murphy with the pride of a father.

“Murphy was ever in good humor and liked to play, but he never neglected his work,” Jordan said. “He never got the big head.”

Murphy first raced professionally in 1875, at the age of 14, the same year that Oliver Lewis, a Black man, won the inaugural Kentucky Derby atop Aristides, a chestnut colt trained by a formerly enslaved man.

Murphy followed Jordan to Fleetwood Farm in Frankfort, Ky., where he began his ascent to national celebrity.

By all accounts, Murphy was reserved and circumspect when he spoke, at least in public. Yet he was able to communicate with horses on an almost mystical level, relying more on minute muscular cues and less on the whip to bring out thoroughbreds’ best performances. Murphy often didn’t keep pace with the pack but appeared to calculate precisely the speed and progress of his horse and those of his opponents, surprising all as he pulled out in front in the last seconds.

In 1879, Murphy rode Falsetto, a dark brown colt trained by Jordan, to a second-place finish in the Derby and went on to take the Clark Stakes at Churchill Downs.

“Murphy is one of the best jockeys in America,” the Spirit of the Times, a racing newspaper, declared after the 18-year-old deftly orchestrated a win in the Travers Stakes in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. “He has a steady hand, a quick eye, a cool head, and a bold heart.”

Murphy won his first Kentucky Derby in 1884 and hopscotched the country — Nashville, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago — his horsemanship winning him entry into whites-only spaces such as San Francisco’s Baldwin Hotel. In 1889, the star jockey was bringing in the equivalent of more than $5 million a year. He and his wife, Lucy, who accompanied him on his travels, bought a spacious brick home near the track in Lexington, where he hired a valet and hosted lavish parties for other African American strivers.

Yet Murphy’s drive to excel and, at least outwardly, fulfill whites’ behavioral expectations of successful Black men took a toll.

As he grew into manhood, Murphy, like all successful jockeys, was forced to maintain his weight beneath the riding limits of 105 or 110 pounds, depending on the age of the colt. The weights included his clothing, saddle and bridle.

His diet was largely fruit, and on race day he walked and ran for miles wearing heavy sweaters, spurning water, Mooney writes in her book. The only time he didn’t feel sick was when he slept. Many jockeys were bulimic, and the deprivations made some suicidal.

For Murphy, whose professional opportunities otherwise were severely limited because of his race, quitting was less of an option. He often left the track shaking after a race, Mooney writes, the demands of commanding a powerful horse at high speeds threatening to break him.

There were other pressures, too, as whites struggled to reconcile their reverence for Murphy and other Black jockeys as athletes with their deep belief in their own superiority. The same racing periodicals that lauded Murphy’s dominance on the track published racist Currier & Ives depictions of Black jockeys buffoonishly failing to control their horses. Early on, Murphy was treated as an exception among Black men. “He was black of skin but his heart was as white as snow,” wrote John H. Davis, a white racing journalist for the American Turf.

And while Murphy laughingly confided to another prominent Black man, “I race to win,” he did not exhibit such bravado in the presence of whites. Anger was also off limits.

According to the New York Sportsman at the time, a young white gambler in Chicago approached Murphy about his mount and began racially abusing him when Murphy declined to elaborate. Murphy “looked at him full in the eye for a moment, and then calmly turned away from him,” at the same time bisecting a fly crawling on his boot with a flash of his riding crop. Black horsemen who witnessed the episode cried out in triumph, the paper said.

A hard fall and the rise of Jim CrowMurphy and other star Black jockeys continued to challenge white society’s expectations about their limits. Aware of their own worth, they hired lawyers to comb over their contracts and threatened legal action when they suspected they were being treated unfairly, Mooney writes. They didn’t just want freedom; they were after equality.

After Murphy guided the vaunted Salvator to a thrilling 1890 victory at the Champion Stakes against one of the country’s best white jockeys, white people reached out to touch him. A white-owned newspaper crowned him “The Prince of Jockeys,” and Salvator’s trainer invited Murphy to a clambake with some of New York’s most powerful men as the only African American in attendance.

That same year, after winning the Kentucky Derby in May, Murphy got caught in an undertow. At the Monmouth Handicap, he uncharacteristically fell off his horse Firenze after crossing the finish line in last place. Rumors swirled that Murphy had been drunk; others speculated that he had been poisoned. In his own defense, Murphy said he hadn’t eaten in two days but also agreed that he may have been poisoned. The controversy burst into public view.

Mooney finds the accusations curious. Jockeys at the time considered alcohol a stimulant, and it was not uncommon to drink on race day. It was an open secret.

“Suddenly, they say: ‘He’s drunk. He ought to be fired.’ That’s where I say, ‘What happened here?’” Mooney said. When she pieces it together — Murphy’s huge success, the explosion of mentions of him in the Black press in connection with civil rights, the growing white resentment as Reconstruction came to a close — she sees racism at work.

Murphy was suspended from racing. “I think that was devastating for him because he experiences it as a judgment from his peers and it damages his respectability,” she said.

The famed jockey never fully recovered, even though he went on to win the Kentucky Derby for the third time in 1891 ± this time riding for a Black owner. Five years after that record-breaking triumph, Murphy died at 35 of heart failure, probably resulting from his rapid weight loss battles, Mooney said.

That year — 1896 — the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of racial segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson, ushering in Jim Crow. Over the next decade, Black jockeys slowly disappeared from the nation’s racing tracks as they came under attack by white jockeys, who began boxing them out during races, running them into the rail and hitting them with riding crops. Four years after Jimmy Winkfield became the last Black jockey to win the Kentucky Derby, in 1902, racetracks around the country prohibited African Americans from competing.

Yet in Murphy’s case, while his glorious reign has faded from collective memory, the high esteem in which he had been regarded endured. In 1955, he was inducted into the National Racing Museum and Hall of Fame in Saratoga, again lengths ahead of the rest.