Duhatschek: Why the NHL should move the Coyotes to Salt Lake City and avoid expansion

Whenever NHL commissioner Gary Bettman gets asked about expansion, he tends to touch on the same talking points over and over again. Usually, Bettman will begin by noting that while the NHL is not actively looking to expand, the league gets overtures all the time from interested parties. If any of the overtures make sense, from a business point of view, they’ll look at them.

Boilerplate stuff and all designed to convey one important underlying message: The commissioner is overseeing a thriving business, and who wouldn’t want to get involved in a thriving business such as the NHL?

Those of us who’ve listened to some version of this communication for decades now sometimes see NHL expansion as a pure cash grab because: A) The cost of joining the league is soaring; B) There do seem to be people willing to pay the rising asking price; C) Best of all, NHL owners don’t need to share expansion fees with the players because it is not factored into hockey-related revenue.

When the NHL added four teams in three years between 1998 and 2000, it cost $80 million to get in. Seventeen years later, the price soared to $500 million for Vegas to join the league. Four years later, the NHL upped the ante even higher for Seattle to $650 million. What’s next? One billion dollars, or more. So, a lot of money.

But let’s go back in time to just before Vegas was granted entry to illustrate a further truth about the expansion process and why some bids are more attractive than others. That time around, once the league formally began to solicit interest, two bids met the NHL’s expansion criteria. The one from Vegas was successful. The other, from Quebec City, was not.

Even though the overture was backed by the considerable weight of a corporate heavy hitter, Quebecor, and had a former Canadian prime minister, Brian Mulroney, stumping on its behalf, the NHL said thanks but no thanks.

And that’s the other little dirty secret of expansion, one that not everybody is prepared to concede. Expansion is partly a cheap cash grab. But it isn’t exclusively a cheap cash grab. Expansion also has to make sense on many financial levels beyond simply lining the owners’ collective pockets with a one-time-only windfall.

This too is a part of Bettman’s consistent messaging and probably doesn’t draw nearly enough attention. He’ll also note that every time you add a team, it shrinks the pie for everyone when it comes to the league’s shared revenues. So, a one-30th slice of the pie became a one-31st slice when Vegas entered the league and a one-32nd share when Seattle joined.

There’s indisputably a secondary financial consideration in play, which is why expansion only makes sense if your newest partner(s) immediately also become one of your most efficient revenue producers. Cash cows, as it were.

This happened with both Vegas and Seattle and also explains why Quebec City remained on the outside looking in. Just too small a market, with too limited a revenue upside, to consider — even though now when Bettman talks about potential expansion scenarios, he tends to drop Quebec City’s name in there. It’s good for optics. But it’ll never happen.

All of which brings us to the latest on the expansion front. News broke last week that a group from Salt Lake City, led by Utah Jazz owner Ryan Smith, wants in. And the league, within nanoseconds of Smith’s statement, acknowledged his overture and in their own curious way, said, ‘We’ll think about it.’ But they also like it on a lot of levels.

LeBrun: Ryan Smith exclusive on taking the next step in bringing NHL to Utah — 'We’re absolutely serious about this'

For those of us in the business of reading the NHL tea leaves, expanding to Salt Lake City now looks like a real possibility. Moreover, if the NHL goes to 33 teams, you can be sure 34 isn’t far behind and eventually, probably, it’ll get to 36.

Objections?

None that should scuttle the bid. On the one hand, even though the current 32-team iteration of the league divides conveniently into four eight-team divisions, the league won’t be too concerned that 33 is an odd number.

In 1979, before the merger with the WHA, the NHL was at 17 teams. Adding the four teams from the WHA brought it to 21. It meant an extra team in one of the four divisions and that kept changing in the early 1980s, when realignments happened in three consecutive years between 1981 and 1983. Ultimately, no one seemed all that hot and bothered about the uneven makeup of the league. In fact, with 21 teams, it meant you could play a fully balanced 80-game schedule — four games each against the other 20 opponents. Nice and neat.

So temporarily being at 33 is not insurmountable.

Then there’s the matter of the available player pool. There is a sense that whenever you add a team, you further dilute the player pool. But realistically, it’s already so diluted that it probably wouldn’t matter much to add 23 additional jobs. Currently, if every team carries a maximum of 23 players, it translates into 736 full jobs at the NHL level. Injuries, and promotions from the minors, mean that as of this past Monday, 834 players have played a single game this season.

Realistically, the difference between the 750th-best player and the 850th is virtually indistinguishable.

Also: The formula to stock the two most recent NHL expansion teams gave the newcomers a fighting chance to become competitive out of the gate because the terms weren’t nearly as punitive as the ones that came before them.

But the main advantage any new team has is salary-cap flexibility. How a team uses that to its advantage ultimately will determine its short- medium- and long-term success. Vegas nailed it almost perfectly. Managers, wary of how much help they inadvertently gave the Golden Knights, were more gun-shy the second time around with Seattle.

But the Kraken still did OK and made the playoffs a year ago and then knocked off Colorado in the opening round.

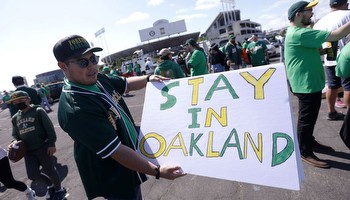

Now the elephant in the expansion room is the Arizona Coyotes. Here’s a team trying to find a permanent home while currently playing in a college arena. Even the NHL believes Arizona’s future needs to be decided soon. The reality is, if the Coyotes can’t get going on a new building and Salt Lake City is ready to go — which Smith says they are — then the easy, and relatively seamless, solution is to transfer Arizona to Salt Lake City.

Of course, that means no expansion fees to divvy up. Just how problematic that’ll be, I can’t begin to say. But it is the sort of question that will divide ownership bases. Some will want the expansion cash infusion. Others might be prepared to look at the bigger picture and figure that it’s worth passing on expansion fees if the Arizona problem can go away, once and for all.

In the end, there are only two choices. Doing the right thing or doing the greedy thing.

The right thing is to let the Coyotes move to Salt Lake City. Player-wise, it’s an appealing franchise. The heavy lifting, in terms of stocking the team with young talent, has already been done. With a little bit of financial backing from a well-heeled ownership to flesh out the payroll, the Coyotes could be formidable fairly soon. Shifting Arizona to Salt Lake City would leave the league at 32 teams and wouldn’t even require the divisions to realign.

Will the league go ahead with expansion? Maybe. Probably.

Should it? Probably not.

And the main reason is competitiveness. If you keep adding teams, it just makes it harder and harder to win a championship.

When the Montreal Canadiens were winning most of their Stanley Cups, it was a six-team league. One chance in six. Pretty good odds. When the Edmonton Oilers were winning most of theirs, it was a 21-team league. One chance in 21. Now, at 32 teams? Significantly lower odds.

The inability to celebrate a Stanley Cup championship — which gets harder and harder to accomplish every time the league grows by another team — does two things. It frustrates fan bases and puts unrealistic pressure on the GMs tasked with constructing a winner because, at the end of the day, only a Stanley Cup matters.

Those close-but-no-cigar seasons — like Florida had last year, or Montreal in 2021, or Dallas in 2020? Gone, in the blink of an eye. And forgotten pretty quickly.

If you expand to 33 teams and then 34 and then to 36, those championship hopes and dreams become ever more remote with every passing year.

And ultimately, a disillusioned fan base could eventually translate into a shrinking bottom line, which is a concept both Bettman and the owners can grasp.

Too many teams is eventually going to be bad for business.

Contraction, not expansion, makes more sense, frankly.

But since the idea of shrinking the league seems to be a pipe dream, the very least they can do is draw the line at 32. And if new viable cities/options come up, such as Salt Lake City, there is always going to be an incumbent or two, struggling at the box office, drawing dollars out of the revenue-sharing system, that will be candidates for relocation.