Greenberg: White Sox broadcaster Jason Benetti isn’t afraid to break the mold

CHICAGO — Jason Benetti is a man of common scents. And like any local worth his celery salt, he knows Chicago is kind of an olfactory town.

An incomplete list of Benetti’s most notable local smells includes the old Wonder Bread factory on S. Archer Ave., the garbage dump off the Bishop Ford, the cotton candy at Great America and Italian beef sandwiches from anywhere.

Of course, there’s the smell of grilled onions at the ballpark. That’s one that represents the confluence of the past and the present for Benetti, who is going into his eighth season as the TV play-by-play voice of the White Sox.

“I think people thought I was nuts when I first got the Sox job and they were like, ‘What stands out?’” Benetti said. “I said the ballpark smells the same. And that was absolutely the first thing that hit me.”

Smell and memory are intertwined thanks to our brain’s anatomy. Odors go from the olfactory bulb in our nose straight to our amygdala and hippocampus, the brain regions associated with emotion and memory. A sense of smell is like a time machine.

And with that in mind, we are transported back to Benetti’s childhood while on the first floor of the Museum of Science and Industry in Hyde Park, where we are standing over a Mold-A-Rama machine, inhaling the aromatic bouquet of cooked plastic as a “space robot” is formed before our eyes.

“It’s like hot wax and it smells,” Benetti said. “It smells like childhood.”

Marcel Proust had his madeleines. Chicagoans have Mold-A-Rama.

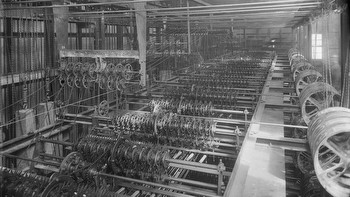

The Mold-A-Rama was created in Quincy, Ill., when J.H. “Tike” Miller started making plaster figurines in his basement to sell to department stores. During World War II, the U.S. banned plaster imports that were coming from Germany, so Miller pivoted to plastics.

He sold the company, which is now based in suburban Brookfield, and it wasn’t until the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle that Mold-A-Rama made a splash. “Fairgoers savored the warm smell of molten plastic as a memory-making sensation,” according to a display at the museum.

As we were looking at a case of old designs, a man came up to us. Benetti is a recognizable face in Chicago, so we figured he was going to ask what Steve Stone was like or what he thought of Tony La Russa, but the curious man just wants to talk about Mold-A-Ramas.

“You guys remember these?” he said. “It reminds me of my childhood.”

Coming soon to The Athletic, a meeting of two Chicago icons, @jasonbenetti and Mold-A-Rama. pic.twitter.com/qpPkPB1WOe

— jon greenberg (@jon_greenberg) March 22, 2023

According to the company’s website, you can find Mold-A-Rama machines in Chicago at the Brookfield Zoo, the Field Museum and the MSI, along with the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Mich., and zoos in Milwaukee, San Antonio and St. Paul, Minn.

But there is something uniquely Chicago about Mold-A-Rama, which, for the uninitiated, is just a plastic mold of … something. A bust of Abe Lincoln, a gorilla, a spaceship, a submarine.

The beauty of the Mold-A-Rama experience is the machine with its bright logo and its steampunk technology. It makes the mold (which is billed as “exclusive” on the machine) in front of you. That is when the arresting smell of hot wax appears.

For most adults who grew up in the Chicago area, the smell of a Mold-A-Rama brings them back to childhood trips to a zoo or museum.

“To me, it’s like, you turn the corner and you go to this exhibit or that exhibit, you go see, like, the cheetahs, and there would be one of these sitting there,” Benetti said. “The actual product being made felt like a toy itself. And then you get another toy.”

We decided the White Sox need to bring these to the ballpark. Imagine the possibilities. How much would you pay for a Mold-A-Rama figurine of Steve Stone?

“Four figures easily,” Benetti said.

Benetti signed a new two-year White Sox contract in late January. But as he told the Sun-Times on Feb. 2, the talks were “kind of a pain.”

Benetti said he and the Sox are on good terms, but he understood when Brewers pitcher Corbin Burnes talked about the awkwardness of arbitration. The big issue between the Sox and Benetti was his schedule.

His life is a busman’s holiday, going from game to game, sport to sport.

This kind of broadcasting polyamory has become in vogue again, with contemporaries like Adam Amin and Joe Davis going national while also staying local. Jack Brickhouse did every sport known to man, but it wasn’t that long ago that Thom Brennaman left Chicago because the Tribune Co. wanted him only to call Cubs games.

Benetti, who signed a national deal with Fox Sports last year to do college football, college basketball and national MLB games, even added a late-season NFL game to his schedule. He previously did national work for ESPN and has also done Olympics for NBC, national baseball games for Peacock, a Bill Walton NBA sidecast and fill-in work on the Bulls. In recent weeks, he did the World Baseball Classic and radio for the NCAA Tournament.

During the season, some people with the White Sox weren’t so keen on Benetti being gone so much for his other jobs — though they have radio guy Len Kasper as perhaps the most overqualified fill-in in sports — and they let him know about it. This is the first year he’ll do weekly Saturday national baseball games for Fox.

After some negotiation, his new contract spells out how many Sox games he can miss — he said it’ll be 35, max — and that should go a long way to smoothing any rough patches with the team, at least for the next two years.

“That was the problem, it was all ad hoc in 2021,” he said. “And then the situation with my games missed was very vague. It’s not vague anymore. So we’re good. That’s done. For me, I thought the work getting better and better and better and better and better might make the level of fairness and respect grow with that. And for some people, it doesn’t. For some people it does.”

Benetti’s frankness in discussing his contract situation comes on the heels of his public complaints when baseball teams cut travel during the 2021 season.

When Benetti got the Sox job in 2016 as the team eased out Hall of Famer Ken “Hawk” Harrelson, he had a “happy to be here” vibe. His story, the hometown kid made good, was instant copy. But now, he isn’t afraid to rock the boat a little. For all the feel-good stories that have been written about Benetti, who has cerebral palsy, he’s no pushover.

“I would push back on that I’m not happy to be here,” he said. “Because I absolutely am. I promise you I wouldn’t be in the booth if I didn’t want to be here and they didn’t want me on some level as well. But I don’t like being told what to say. And I want to be emotionally honest, with what matters to me like that. The two instances you brought up are frustrating to me. Because, well, because I love doing this so much.”

Benetti has thought about taking up golf. But he knows that no matter how much he works at it, he’ll never be a great golfer because of his physical limitations.

“Good just doesn’t appeal to me,” he said. “Because if I’m good, and I look like this, people then will start to treat me like I’m great. But I’m not. And I’ve always been offended by that.”

It might surprise you that he isn’t a fan of the feel-good sports stories that go viral. You know the ones, where the manager with a disability gets to run for a touchdown or take a 3. Something about them makes him uneasy.

“That’s always been really hard for me to watch because I know it’s really good for the person in that moment and it’s good for society, but I don’t love watching it,” he said.

At 39, Benetti still feels that because of his cerebral palsy, people might not take him seriously. Actually, he doesn’t feel it. He knows it.

He deals with well-meaning helpers at the airport. He’s constantly being offered an elevator or a ride. He doesn’t want sympathy, he just wants empathy. While he has grown into being a role model and while he knows that this is part of his identity forever, he still bristles when he feels he’s being treated differently than, say, other people in his profession. Like he should feel grateful for where he is.

“I guess I thought it all was going to go away at some point, like when I was an adult, that people would treat me with equal respect or when I became, quote, unquote, a great announcer,” he said. “That’s never going away. People are going to see me for what I am, which I love in a lot of ways. I love that I see the world in a different way. But sometimes it’s like I doubt you would treat somebody who looks quote, unquote normal, like this.”

Benetti said he loves the documentary “Crip Camp” about how a summer camp for kids with disabilities in the 1970s produced adults who became disability rights activists.

“Early on, one of the kids said if you have a disability and you have a passive personality, you’re probably screwed,” Benetti said. “I’m not always just the happiest person in the world. Because if you transported anybody into my shoes, for three months, they’d have some moments where they were pissed off because they’re not getting treated like they were before.”

There is a push and pull with the reality of dream jobs. Benetti never thought he’d be on TV — his realistic goal was being a college basketball radio guy — and he calls his wealth of opportunities “house money.” But that doesn’t mean he’s content.

“I never really wanted to be the TV voice of anything, because … I’m not trying to be maudlin, but the odds of that are pretty small no matter how you look,” he said.

But now he’s on TV and he’s great. He’s happy to be here and he knows he earned it.

While there is no mold for Benetti, who is sui generis, there is one for the old Talman Bank Building on S. Kedzie Ave.

Wait, what?

Yes, Talman Bank is one of four specialty Mold-A-Ramas available for purchase for $5 at the exhibit, much to our delight. The blue plastic replica of a bank he has never visited was the only one Benetti wanted to take home.

“This is the most Chicago thing that has ever existed,” Benetti said. “It’s a Mold-A-Rama of a bank on Kedzie. It’s the most Chicago thing in the history of the world.”

Benetti speaks with a Syracuse broadcasting affect, but he’s Chicago at his core. He peppers conversations with impersonations of old Chicago radio ads and Ed Farmer calls. He loves the ridiculousness of a big city that feels like a small town.

He’s not looking to leave the Sox, but at the same time, he won’t tearfully retire in the booth as Harrelson did. He loves working with Stone, whom he thinks will handle the new faster pace of baseball better than any color guy in the game, and being teammates with his close friend Kasper. He loves calling games on the South Side. That’s good enough.

“I don’t know if you meant to do it, but the reason I’m still here is like the Mold-A-Rama,” he said. “There’s an allure (to the White Sox) that is undeniable. You said it, I’ve been frustrated. But I’m still here and I’m not looking around, saying, ‘Why am I still doing this?’ I could have not done it. And they could have moved on. We didn’t because it’s kind of like a sense memory. It’s stupid, but it’s true.”

What does contentment look like? Benetti isn’t sure. But for now, he knows how it smells. Like Grilled onions and hot plastic. Like home.

(Top photo of Jason Benetti: Jon Greenberg / The Athletic)