How Britain's first black pro footballer never played for England but was a world champion at something else

WHEN the Three Lions gather at their training HQ, they pass the giant statue of a goalie making a fingertip save.

The 16ft colossus hewn in bronze at St George’s Park, Staffs, shows the leaping figure of Arthur Wharton and is designed to inspire success against the odds.

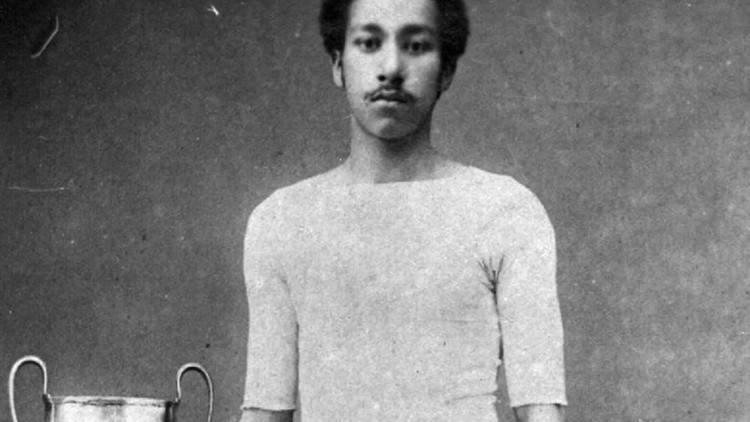

For trailblazer Arthur was Britain and the world’s first black professional footballer and also the fastest man on Earth.

Arthur was on the pitch when Liverpool played their first ever game at Anfield and reached the FA Cup semi-final with the then giants of the game Preston North End.

Gary Lineker wrote of the showman who was footballing box office gold in the 1880s: “He used to catch the ball between his legs.

“He would sometimes pull the crossbar down (it was made of tape in those days) so shots would miss.”

Though blessed with supreme talent, Arthur would never pull on a Three Lions shirt.

Shaun Campbell, director of the Arthur Wharton Foundation, said: “There was quite a strong call for Arthur to play for England but the colour of his skin, it was said in the day, denied him that opportunity.”

Sheffield United star Arthur had to battle against vile prejudice in Victorian Britain.

Once, when competing in an athletics race, he overheard fellow competitors calling him the N-word.

Arthur turned to the two men and told them: “Allow me to give you to understand, I not only run but do a little boxing when required.”

The abuse soon stopped and Arthur duly won the race.

The extraordinary story of how a Ghana-born trainee missionary had lit up our national game had largely been forgotten until the 1990s.

World record

Now a National Lottery-funded short film called, A Light That Never Fades, starring Play School and Coronation Street star Derek Griffiths, will chart Arthur’s struggle against adversity.

It’s hoped Hollywood might now come calling too.

Arthur was born in Jamestown (now Accra in Ghana) in the then British colony of the Gold Coast in 1865 into an upper-middle class family.

His merchant father Henry Wharton was a Methodist preacher from Grenada in the Caribbean and was of African and Scottish descent.

Mum Annie Florence Egyriba was a member of the Fante Ghanaian royal family.

Young Arthur — whose Ghanaian name, Kwame, comes from the day of the week he was born on — initially followed his father into the church.

In 1883, at the age of 19, he left behind sweltering West Africa to train as a missionary at windblown Cleveland College in Darlington, Co Durham.

Soon the young man discovered a life in the pulpit was not for him, later telling a newspaper that religion was “not my inclination”.

But Arthur could run like the wind.

He started playing football as a goalkeeper — a surprising position given his pace — for Darlington, who were then an amatuer team.

At 6ft tall and with an extravagant black moustache, Arthur must have cut a dapper presence on the pitch.

And like many goalkeepers since, Arthur gained the reputation of being an eccentric.

Reports say he would crouch at the side of his goal when outfield play was threatening then dash into position to make a save.

A newspaper article would later recall: “I saw Wharton jump, take hold of the cross bar, catch the ball between his legs and cause three on rushing forwards to fall into the net.

“I have never seen a similar save since and I have been watching football for over 50 years.”

But Arthur was described in reports during his playing days at Darlington as “magnificent”, “invincible” and “superb”.

On occasion he would use his dazzling speed to play on the wing.

Arthur then joined Preston North End. With the Football League yet to be formed, the FA Cup was the season’s glittering prize.

He was in nets for the team that reached the semi-finals of the cup in 1887.

A first-class athlete, he later became a professional cricketer, cycling champion and a rugby player.

In 1886 Arthur broke the 100-yard world record, finishing the race in exactly ten seconds at the Amateur Athletics Association National Championships.

The record stood for over 30 years. Jamaican eight-time Olympic gold medal sprinter Usain Bolt would later pay tribute to the former preacher’s groundbreaking career, saying: “Without Arthur, there would be no Usain Bolt.”

Arthur’s football career was also taking off and in 1889 he signed for Rotherham Town as the world’s first black professional player.

Then in 1894 he joined Sheffield United and became the first player of African heritage to play in the top flight of English football.

At the time, players at the club could earn about £3 a week — £400 in today’s money — plus win bonuses.

The average weekly wage of a working man was £1.

Arthur also took over running the Sportsman Cottage pub in Button Lane, Sheffield.

He saw out his career playing for Stalybridge Rovers, Ashton North End and Stockport County before retiring in 1902.

Nicknamed “Darkie” while playing, he contended with the overt racism of the era.

When Arthur joined Stalybridge in 1896, the local paper wrote that the club had “bagged itself a real n****, none other than the Darkie who used to guard the North End citadel”.

After hanging up his boots, Arthur settled in South Yorkshire and worked as a miner for 20 years while succumbing to the bottle.

His complicated personal life saw him have an affair with his wife’s sister. He died penniless of cancer in 1930 aged only 65.

Arthur was buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave in the village of Edlington near Doncaster.

‘Imagine his courage’

Despite being a trailblazer for black and mixed race players, Arthur’s name was largely forgotten.

It took organisations like Football Unites, Racism Divides to revive interest in the footballing pioneer.

In 1997 the charity raised money to have a headstone placed on Arthur’s grave.

England’s first black international, ex-Nottingham Forest defender Viv Anderson, only discovered Arthur’s existence through an exhibition at the National Football Museum in 2003.

Viv, who won his first of 30 England caps in 1978, said: “I didn’t know his story until then — and I was a black professional footballer.”

Slowly football was re-discovering its forgotten son.

In 2014 the colossal statue of Arthur, by sculptor Vivien Mallock, was unveiled at St. George’s Park, the FA’s National Football Centre.

Its chairman David Sheepshanks said at the time: “When you look at what this man achieved it’s simply extraordinary. Imagine the courage he had to display to achieve what he did.

“We often talk how hard it is for young people from black and Asian minority backgrounds to get into top jobs today, so imagine what it was like then.”

In the same year Arthur’s great-granddaughter Dorothy Rooney discovered a trove of his photos and documents and took them to the BBC’s Antiques Road Show. It included his personal Bible.

Dorothy said: “My mother and I found some old photos of Arthur and traced him back.

“We have actually been to Ghana and met family members, and they didn’t know of Arthur. He was a Victorian sporting hero.”

A huge two-storey-high mural of the player in Darlington was completed in 2020.

The latest boost to commemorate Arthur is the short film which will be shown at schools in the North East where his career began.

Now there are hopes his remarkable story will be given the big screen treatment.

Shaun Campbell, from the Arthur Wharton Foundation, added: “We are working towards bigger projects telling Arthur’s story on film. It could be extremely exciting.”

It would be a fitting testament to a man whose gravestone epitaph reads: “The dust of his toil laid traces that will never be covered.”