How MLB could keep the chaos while improving the playoffs

Baseball's owners are meeting this week in Arlington, Texas, home of MLB's newest champion, the Rangers, whose celebratory parade rolled through the wide boulevards of the area less than two weeks ago.

One item up for discussion, as per commissioner Rob Manfred, is the sport's new playoff format, the one that crowned the Rangers this year and the Astros in 2022, MLB's first postseason under a 12-team structure.

We probably shouldn't expect anything to change in the short term, given the tenor of Manfred's recent comments. "It's only Year 2," Manfred said during the National League Championship Series, largely responding to concerns that the top seeds were flopping in the division series after an extended layoff created by the new best-of-three wild-card round.

Two years does not tell us if the bye is actually a problem. So far, it's just a thing that has happened, and not uniformly. The Astros have dealt with the layoff just fine in both seasons, for instance. Historical research looking at similar layoffs through playoff history suggest they are a boon, not a penalty. There is not a manager in baseball who would forgo a first-round bye if given the option to do so, which tells you all you need to know.

That doesn't mean baseball's postseason format has been perfected -- though the definition of perfection varies. For some, it's about crowning the most worthy champion. For others, it's about maximum chaos. The hope is that the ultimate motivation among the owners is finding a happy medium.

What do we want from the postseason?

Two years into the new structure, the 12 division champs have played a total of 15 LCS games (seven by this year's Astros, four each by last year's Astros and Yankees). They have played just six World Series contests (the six by the 2022 Astros).

And this year's Fall Classic gave us this:

The 2022 Astros won 106 regular-season games en route to the championship, and the combined winning percentage of their World Series matchup against the Phillies was a historically unremarkable .596. This tells us that it's not impossible for the best teams to win in this format. Not every season is going to be like this one.

Nevertheless, the general lack of success of division winners over the past two seasons ought to give the owners pause. Is this really just a fluke or is it the beginning of a new norm? Or perhaps the better way to ask the question is simply, "Can we do better?"

First place has generally been a sacrosanct thing through baseball history. For decades, it was the only route to the playoffs, from the World Series' inception in 1903 through 1993, the last year without a wild card. Things have changed since then, with each expansion of the playoff format chiseling away at the rewards for finishing first. We've generally come to accept this in baseball and, sure, maybe finishing first doesn't have to be everything.

The problem is that it also shouldn't mean nothing, or something close to that. The concern isn't so much that we'll end up with a spate of lackluster World Series matchups, which would be a problem, but more that this new reality will have a corrosive effect on the integrity of the regular season. This is basically the concern expressed by MLBPA executive director Tony Clark.

A fundamental problem with a large playoff format is that even as people get excited about the race for the last few playoff spots, the attention focused on that part of the standings takes away from the focus on the top part of the standings.

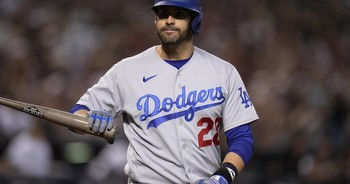

When you pair that with a lack of success for the top two seeds because of the inherent randomness of any playoff series, it could disincentivize teams from building themselves up to the level of a powerhouse. Why make the investment if all you really can do is just worry about getting in? The Dodgers have won 10 of the past 11 NL West titles, and were a 106-win wild-card team in the other season. They have one championship (and that one in the shortened 2020 season) to show for it. Why flex your muscles as an economic behemoth if all you get is a spot on a bracket?

There have been numerous suggestions floated for tweaking the playoff format and eventually it needs to be tweaked. When that happens, the focus should be on one thing: Enhancing the regular season and the rewards that come with actually winning something over the long haul, baseball's most distinctive and endearing characteristic.

The size of the playoff field is not going to get smaller. Professional sports leagues do not contract their playoff fields, they grow them. The economic rewards for a healthy stock of postseason games is too lucrative to set aside. But we need to make sure there is a meaningful reward for finishing first during the regular season, and a clear distinction between the values of each tier of playoff seeds.

This is not easy to accomplish because of the inherent randomness of the baseball small sample, which is both its greatest trait and, sometimes, its worst enemy. There is talk about making the LDS a seven-game series -- which should probably happen, but we might then need to clip games off the regular-season schedule. It still would be uncomfortably random. Researchers have suggested that for a baseball series to truly be representative of the relative strength of two opponents, it would need to be around 75 games long. Not going to happen in this world.

So do we just throw our hands up and wait with bated breath until baseball's inevitable crowning of a sub-.500 champion? No, there are things we can try.

Five things MLB could try

1. Crown a regular-season champion

Here's a modest proposal, made at a time when the NBA is conducting its first-ever in-season tournament. It's hard to imagine something similar happening in baseball, but it does reflect a growing recognition of leagues to ensure the quality and intensity of regular-season competition.

For baseball, rather than a tournament, we should create two awards, one for each league, that recognize the best regular-season teams. Name the awards after someone of historical prominence -- Rube Foster, Branch Rickey, Ban Johnson. More importantly, make a big deal about them. Award a cup or trophy. Give a massive financial reward for winning it. Add it to the history books, so we might say something like, "The Dodgers have won seven Branch Rickey Cups over the past 11 years."

And, most importantly, make the most tangible reward a No. 1 playoff seed that actually is worth pursuing. When we see a team pile up on the field after clinching its league's best record, we'll know we have created something worth winning.

2. Go back to four divisions

The biggest problem with the current format is that in each league there is a division champion who is treated like a wild card. There is no meaningful distinction between being a No. 3 seed (which is a first-place team) or being a 4, 5 or 6.

Yes, that third seed is guaranteed to host its best-of-three wild-card series. That's better than not hosting, but as we've seen over the past two years, that doesn't get you much. This is a problem not just for the 3-seeds but in all playoff series. The chief benefit in a series for being the higher seed is home-field advantage, but that doesn't mean as much as it used to, nor as much as you think it does. Even if it meant more, it's not an advantage that will necessarily manifest in a short series.

This season was an extreme example, but home teams went 15-26 during the postseason. It was the fifth time since 2010 that we've had a playoff season in which road teams won more games. It happened just three times during the first 15 years after the adoption of the wild card.

This mirrors an overall erosion of home-field advantage in baseball over the years. Home teams won just 52.1% of the time this season, the lowest figure since 1999. The five-year home winning percentage (53.3%) is lower than it has been since the 1997-to-2001 period (53.2%), which is near the low-water mark for the division era (53.1%, 1971 to 1975). To incentivize teams to value the difference between seeds, we need to offer more than home-field advantage.

The first-round bye, in theory, is a big incentive, even if it has seldom played out that way the past couple of years. That should even out in time, but when it does, that still doesn't help our No. 3 teams, the division champions who are really just wild cards.

If we have just two divisions per league, that problem goes away. You win your division, you get a bye. That is a clear incentive. That enhances the prestige of being a division champion.

This structure of two divisions per league is something that should be adopted even when baseball invariably expands to 32 teams -- assuming MLB sticks to a 12-team overall format. Further expansion of the playoff field changes this calculus.

3. Bring on the ghost win!

In October, Clark told the media that during the last round of CBA negotiations, when the subject of playoff format was raised, the MLBPA advocated the introduction of a ghost win for division winners consigned to a wild-card round. This concept is employed frequently in leagues around the world, though it has never been tried in MLB.

If you haven't heard of it, all it means is that in a series that uses the ghost win, the higher-seeded team has to win one fewer game than its opponent. The favorite ostensibly starts the series with a 1-0 lead already in its hip pocket.

The idea is a good one, and would have a significant impact over time. If we stick with the current six-division setup (as owners and the commissioner likely favor), then the MLBPA's notion should be adopted. However, if we are looking at things holistically and adopting our second suggestion here -- the return to a four-division setup -- then the "ghost win" should be deployed for the top seeds in each league.

Win your regular-season pennant and get a celebration, a cup, a whole lot of money, a bye and a meaningful leg up in your first playoff series. Perhaps we wouldn't usher in a return to the days of the pre-division era, when finishing first was everything, but the combination of these factors would get us as close to it as we are likely to get in a large playoff field.

There are different options for doling out ghost wins that are worth considering. You can give one to the top seeds in each league only. You could do this for just the LDS or do it in the LCS round as well. Or you can give one to both bye teams in the LDS and one to the higher seed in the LCS, provided it's a division champion.

4. Begin re-seeding

As much as everyone loves a bracket that's clean and easy to anticipate, reseeding is a meaningful tool. Not doing so has an undesired effect on the top overall seeds. Every time a 6-seed topples a 3-seed in the wild-card round, that means the top seed faces a tougher opponent than the 2-seed in the LDS round. The top seed's fate has gotten more dire before it has even played a postseason game.

Obviously, there are a lot of moving parts in a given season, and when the 6-seed loses, it's not an issue. But the National League has sent 6-seeds to the World Series two years in a row, so it's a subject worth considering. When you reseed, not only does the 1-seed always have the easiest path, but the flip side is that the 6-seed always has the most difficult one.

5. Consider some other options

If we adopted the above items, these other suggestions really would be more overkill than anything. We will list them as food for thought:

• No layoff between the end of the regular season and the start of the wild-card round

• No layoff between the end of the wild-card round and the start of the LDS

• Give the lower seeds one home game only in the LDS round

• Make the LDS a best-of-seven series

• Allow higher-seeded teams in the LDS to choose their opponents

• Give the higher seed five home games in a seven-game series

There are other suggestions that would involve trimming the regular season or the number of playoff teams. Again, the assumption here is that these things aren't going to happen.

How new formats would rock October

Let's put some numbers to how these changes might play out. We'll use a Monte Carlo simulator to run the playoffs 1,000 times each using three possible formats:

1. The current format, to provide a baseline.

2. A revised format with four divisions, reseeding between the wild-card round and the LDS round, and a ghost win in the LDS for the league's top overall seed.

3. A revised format with four divisions, reseeding between the wild-card round and the LDS round, and ghost wins in the LDS for the league's top two seeds, plus the higher seed in the LCS.

We're not using actual team ratings in this exercise. Instead, each squad is rated as a 90-win team so the differences between them are entirely dependent on seeding and the home-field advantages that go with each seed.

Baseline simulations

The current format

The actual probabilities don't look like this, because teams aren't equal in ability. But this is roughly the starting point if each team had the same underlying ability and were seeded one through six in each league using the current playoff format.

There's a clear division between the top two seeds, which get a bye, and the rest. But there isn't that much separation between one and two, largely because we don't re-seed between rounds and often the 2-seed ends up with the easier path.

All things being equal, there's around a 66% chance a division champ wins the World Series in a given season, and a 52% shot that the champ is one of the teams that earned a bye.

The one-ghost format

Now let's run the same simulations, only now there are just two division champs in each league and the top overall seed gets a ghost win in the LDS round. We are also reseeding.

Now we are getting somewhere. The top seeds have gained 5% on their title odds. Those gains are coming at the expense of those teams further down the seeding ladder, but we aren't stifling the 2-seeds. Even though we have two fewer division champs, we're still getting a first-place champion almost as often (62% division champions vs. 38% non-division champions).

The beauty of this format is that it retains the difference in seeding tiers between the bye and non-bye teams while offering a meaningful difference between seeds 1 and 2. The 3-seeds don't gain anything, but the perception of them is different because no longer is a division champion being lumped in with the wild-card teams.

The three-ghost format

Now let's run the same simulations only now we'll give a ghost win in the LDS round to both bye teams and also award one to the higher-seeded team in the LCS.

Admittedly, this version of our revised structure might be a little too extreme. Top seeds become almost a fifty-fifty proposition to win the pennant in a given league and in reality, they'd be well above that given a real distribution of talent (combined, the two division champs would have a 76% chance to win the pennant). They'd both have a one-in-four shot or better to win it all. Wild-card teams would still have a shot, but you probably aren't going to bet on them.

The best aspect of going all-in on the ghost win concept is that we end up with a division champion as our World Series winner more than three out of every four seasons. That feels like a win for proponents of the regular season.

The bottom line

The message here isn't that baseball should adopt one of these proposed formats as sketched out here. The league can figure out its own format, and there is lots of room to play with the numbers. All of the ideas that have been alluded to here would have at least some effect. It's up to the owner and the league office to find the right combination.

When defending the current system last month, Manfred said, "One of the greatest things about the playoffs in baseball is anybody can win."

That is really a matter of your perspective, about what you think the playoffs ought to be about. The current format doesn't do enough to reward baseball's best teams for their success from the end of March through the beginning of October. Whether you consider that more a bug than a feature is really up to you.

The important thing to keep in mind is that there are lots of ways for baseball to nudge things in whatever direction it wants. Hopefully that means figuring out a way to ensure that the luster of a first-place finish -- winning a flag, taking the pennant -- isn't lost in the haze of randomness.

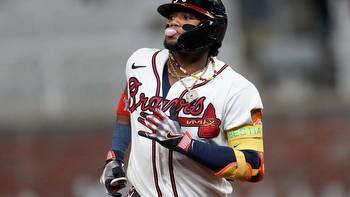

The "anyone can win" aspect of the baseball postseason isn't going away, not as long as we have a dozen teams playing into October. What we want to ensure is that Cinderella teams like this year's Diamondbacks remain the exception, not the rule, a special case that we can all savor rather than dread.

After all, the fairy tale would be a lot less interesting if the glass slipper fit everybody.