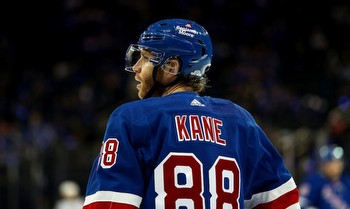

Inside the surgery that changed Patrick Kane’s career and the rehab that changed more

A lot can be accomplished in 11 hours — and a lot can go wrong.

That, roughly, is how much time elapsed on Nov. 28 between The Athletic’s report that Patrick Kane had chosen to play for the Detroit Red Wings and the team’s official announcement later that day.

In between, Kane, owner of 1,237 NHL points and the most impressive trophy case in the history of American hockey, met with the Red Wings’ medical and performance staffs to show off something else he’d picked up over the summer: A cobalt-and-chromium-coated right hip joint. Those meetings were neither brief nor a formality. Kane’s future with the franchise, and the career arc of one of his generation’s greatest playmakers, hinged on what they uncovered.

Everyone, Red Wings general manager Steve Yzerman said, liked what they saw. “They’re pretty extensive in their evaluations of players for their return to play,” Yzerman said, “and they were really pleased with the results.”

The next day, with ink to paper, Yzerman and Kane were free to meet with the media. Both said they were optimistic about what lies ahead, which is to be expected. Beyond that, though, both sounded genuine. They sounded like they were excited. They sounded like they were sold — on Kane’s prognosis, sure, but also on a niche procedure that, for the last 10 years, has existed publicly in the Venn Diagram overlap of last resorts, career-enders and saving graces.

GO DEEPER

What can Patrick Kane do for the Red Wings? Maybe more than you think

“I think the thing that got me,” Kane said, “was the fact that (surgeon Dr. Edwin Su) believes that I won’t have to retire because of my hip now.”

When Kane takes the ice later this week, he’ll become just the third NHL player to return from hip resurfacing, following Ed Jovanovski in 2014 and Nicklas Backstrom in 2022. Ryan Kesler had the procedure but never returned to an active roster. Carl Hagelin had it, too, but an eye injury ended his career before he attempted to play on the hip. If Kane stays in the lineup for the rest of Detroit’s season, he’ll have played more post-surgery games than them all.

Resurfacing — an alternative to a full hip replacement that involves shaving damaged bone and cartilage from the femur, capping that bone with metal and popping it back into a lined socket — has high-profile test cases in tennis (Andy Murray) and pro wrestling (The Undertaker). Murray, in particular, is an idealized patient: a young, otherwise healthy person who was unwilling to accept the physical limitations that are part-and-parcel with a traditional hip replacement.

There is no NHL analog for Murray, though, especially in the wake of Backstrom’s stalled comeback for the Washington Capitals. The fact Detroit signed Kane to a one-year deal reflects that inherent uncertainty.

The belief, held by the player, the team and its medical staff, is still that Kane can be that person, even at 35. It’s shared by Su, an orthopedic surgeon at New York City’s Hospital for Specialized Surgery who has performed thousands of hip resurfacings over nearly two decades, including The Undertaker’s, Jovanovski’s and Kesler’s. Success stories are important to him; the procedure accounts for less than 1 percent of all yearly hip replacements in the United States, and he believes that number should be higher, especially, he says, now that lower-quality implants and less committed surgeons are no longer in the mix.

Kane, in the six months since his surgery, “has reset the whole recovery timeline” — and not just for hockey players.

“(Kane) really is, like, kind of freakish,” Su told The Athletic. “He’s just blowing it out of the water. Things that we expected to be accomplished by three months, he did in six weeks. Things that we expected in four months, he did at two months. He’s basically accelerated the timeline by almost a half.”

GO DEEPER

NHL attendance analysis: Biggest risers and fallers year-over-year

The hip, Kane said, caused its first problems during the 2020 playoff bubble in Edmonton, though he still managed nine points in nine games before the Vegas Golden Knights eliminated his Chicago Blackhawks. Less than five months later, in January 2021, Kane came out hot at the start of the 56-game season, putting up 34 points in his first 23 games and maintaining momentum until the schedule was complete. He finished with 66 points.

“I’m like, ‘Good, I think I can run it back and not just get the surgery,’” Kane said. At that point, he would’ve likely had a more standard arthroscopic procedure, featuring clean-up work but no metal implants. Kane’s production that season — 92 points in 78 games — stayed up amid abysmal team play.

“(After 2021-22) I’m just thinking, ‘I can play with this, this is just the way it is,’” Kane said. “‘I’m not going to be at the level I was before, but I can still be an effective player.’”

That offseason, months after the revelation that the organization had grotesquely mishandled Kyle Beach’s 2010 sexual abuse allegations against former coach Brad Aldrich, the Blackhawks pivoted to losing on purpose. Gone were Kane’s former running mates Alex DeBrincat and Dylan Strome, along with many of Chicago’s other viable NHL players. The lure of improved odds at reeling in Connor Bedard was strong, and Kane began the 2022-23 season in an unpleasant spot — as trade bait on a tanking team, with his hip in a similar state of disrepair. He was playing “straight-legged,” he said, with severely limited lateral movement. Left-to-right crossovers posed a particular problem.

“It probably wasn’t even a crossover,” he said. “It was more of hopping on my left leg to get over to my right side.”

Kane still managed 45 points in 54 games, aided by 10 in his final five as a Blackhawk, before waiving his no-movement clause and landing with the New York Rangers. After 19 nondescript regular-season games — the grand plan of Kane rekindling his chemistry with erstwhile linemate Artemi Panarin never materialized — and a first-round crashout against the New Jersey Devils, Kane reached a crossroads. He was set to hit free agency for the first time after 16 seasons; he was also dealing with a damaged hip that could no longer be ignored.

“I didn’t want it to be the reason I had to stop playing,” Kane said, “and (surgery) was a decision that was talked about pretty deeply to make sure we made the right decision.”

On June 1, in an operating room on the Upper East Side, Su finalized the decision with a cut through Kane’s thigh. Almost exactly a decade earlier, he’d made the same one on a hockey player for the first time.

When Jovanovski visited the Hospital for Special Surgery in March 2013, he was nearly 37 with a huge frame and physical style that put more ticks on the odometer — and out of options. He’d already spoken to other hip specialists. Su wasn’t the first surgeon he saw at HSS; Jovanovski walked into the building for his consultation with Dr. Bryan Kelly assuming that it’d end with an arthroscopic procedure. That’s not the way the meeting unfolded.

“(Kelly) looked at me and he’s like ‘Dude, your (playing) days are over. You’ve got to go see my partner in the back,’” Jovanovski said. “I’ve never heard of hip resurfacing before. I mean, I’ve heard of hip replacements.”

A replacement — where the femur head and socket would be swapped out for metal prostheses — would end Jovanovski’s career. A resurfacing would smooth out the bone-on-bone impingement causing Jovanovski’s problems, similar to an arthroscopy, while also strengthening the joint and maintaining more of his original bone.

Su, who’d been performing the operation for nearly 10 years, made things easy. “He was like, ‘You’re young enough, you’re active. Your bone density is like a dinosaur’s. So I think you’d be a great candidate for this.’

“And at that point, when you can’t bend over and f—— tie your shoes anymore or put your skates on, you’re at the point of trying anything.”

The main trade-off, aside from the pain of the procedure itself, was the chance, however small, of violent impact at the exact wrong spot. “If something bad happens, breaking that femoral neck means that you’re going to go into a total (hip replacement),” Jovanovski said.

Soon thereafter, Jovanovski was on the operating table. Su made the cut, dislocated his femur, pulled out the bone, shaved it down, added metal and hammered everything back together. After 10 months of grueling rehab, Jovanovski returned to the Florida Panthers lineup and made some history; he is believed to be the first professional athlete, outside The Undertaker, to play after the procedure. He got 36 more games, and then he was done for good.

“Ed is a pioneer,” Su said.

It’d be easy to attribute the end of Jovanovski’s career to the hip; according to him, it’d also be incorrect. When the Panthers bought him out of the last season of his contract, his leg felt stronger than it had in years. Sometimes, he said, it’s just time.

“I felt like with a full summer of rehabbing and working out that I probably still could have played, but (I had) four kids,” Jovanovski said. “I had a 19-year career and it was good. At that time (the procedure) was pretty fresh, right? So no one’s really going to take that crack on you.”

More than nine years later, Jovanovski’s resurfaced right hip still feels great. Stronger, he said, than his left — a full replacement done after his retirement. He works out in South Florida five times a week, still singing Su’s praises and still bringing up the moment he knew he made the right choice.

“The day that I could bend over and tie my skates,” Jovanovski said, “it was like, ‘wow.’ It was good.”

Kane is aiming for more. The optimism surrounding him goes beyond simply being younger, smaller and less physical than Jovanovski, Su said. The decision to resurface was meant to cut to the chase — especially given the likelihood that a simple bone shaving would’ve given way to a resurfacing a year or two down the line. Kane’s hip, impingement aside, hadn’t been fussed with all that much.

That’s a key point of differentiation with Kesler, who’d had two separate operations on his right hip, missed loads of games and endured brutal off-ice discomfort before his resurfacing in 2019. In a statement announcing the procedure, he called it “the best option” to live a pain-free life.

“Previous athletes, we probably would have tried everything,” Su said. “They would have had injections, physical therapy. They would have probably done arthroscopic hip surgery. They may have done repeat hip arthroscopy … (With Kane) we just kind of skipped that intermediate scope step and (went) right to resurfacing.”

After the resurfacing came the rehabilitation. With the rehabilitation came Su’s biggest reason to believe Kane can convert all that optimism into tangible success.

Kane’s work started the moment he left the operating table. He stayed in New York City for a month, working out with a top physical therapist on a low-impact skating treadmill. That emphasis on sport-specific treatment wasn’t part of the plan for Jovanovski, Su said, using it as an example of the progress they’ve made since 2013.

“He was getting the movements back, even if he wasn’t fully strong,” Su said. “We were letting him do these sports-specific treatments right away, which I think helps ease the transition.”

Rediscovering his skating motion — learning how to control and strengthen the muscles that the procedure unlocked — was the skeleton key for Kane’s accelerated recovery, Su said. He was skating in mid-July, six weeks post-op.

“It’s kind of a rare situation that you have someone as good an athlete as he is, who is still willing to work hard and wants to recover and is not too far off his prime form to have the surgery,” Su said. “So that is really, really exciting to see.”

After 10 weeks of skating, around Oct. 1, Su cleared Kane to take contact. In other words, he could’ve signed and practiced with the Red Wings before they played a game. Instead, he skated dozens of times on his own, continued working out and waited to see what the offers looked like at the end of November.

“Do I feel like I could have played (at the start of the season)? Yeah, maybe. I don’t know if there’s that much of a difference from where I was two months ago to now,” Kane said after he signed. “We thought it was smart just to kind of wait to the six-month mark and be smart about the whole thing.”

Now, here he is, pain-free and on an up-and-coming team that he’d eyed from the start. The Wings got themselves a potential difference-maker, the exact sort of play-making presence on a top six that they’d lacked. You could almost hear the gears turning in Yzerman’s head at the press conference, just as you could almost hear him tapping the brakes. He’s excited to have Kane on his team, and he’s also aware that they’re largely swimming in uncharted waters.

Su, meanwhile, has his own set of reasons to root for Kane’s success this season and beyond. He wants hip resurfacing to have another lodestar, and for his patients to have another role model. That, he says, has already been accomplished.

“Not everybody’s going to have (Kane’s) dedication and hard work ethic, but if they’re the same age, they have similar bone quality and they want to do some athletics, we’ll start to push the envelope, I think, to let them do more earlier,” he said. “It’s eye-opening for the whole procedure and what we thought was possible for other patients.”