Jimmy Murphy, the legend behind Old Trafford statue: ‘Manchester United wouldn’t exist without him’

The elderly man walked to the stage, wearing a tie in Manchester United’s colours, looked out at the sea of faces in front of him and thanked everyone for sharing his family’s proudest moment.

His name was Jim Murphy Jr and, behind him, two huge banners were emblazoned across the walls of Old Trafford. Both carried quotes from his father, Jimmy Murphy. Both told us a lot about the man who, posthumously, was about to get his own statue outside the Stretford End.

“It can be done, it will be done, I’ll make sure of it,” said one.

On the opposite side: “We have the greatest club spirit in the world.”

His family were watching from the front row as the ribbon was pulled, the red robe fell away and the sculptor, Alan Herriot, explained why this statue was so necessary.

“Let’s face it,” said Herriot, “Manchester United wouldn’t exist without Jimmy Murphy.”

That, in a nutshell, is why Old Trafford’s statue count has gone up from three to four and, like the others, that Murphy’s part in United’s history qualifies him for genuine greatness.

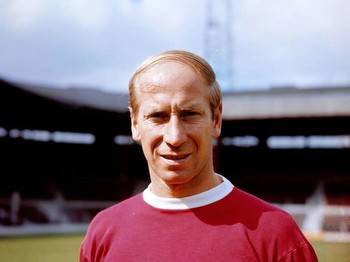

Sir Alex Ferguson is immortalised in bronze outside the stand that is now named after him. At the front of the stadium, a statue of Sir Matt Busby looks over the forecourt. Staring back is the Holy Trinity: George Best, Denis Law and Bobby Charlton. Law’s right hand is raised, index finger pointed to the skies. Charlton is one side of him, Best the other. All of them, you imagine, would understand why a club with United’s back story wanted to honour the phenomenal life and career of Murphy.

“When you come out of that dressing room and you are representing Manchester United, you are taking some of Jimmy Murphy’s mindset with you,” Ferguson once said. “Planting the seed of what that man did, telling them what that man did, is the biggest thing you can tell a young player representing Manchester United.”

Perhaps some younger fans are not fully acquainted with Murphy’s role before and after the 1958 Munich disaster. If so, his statue’s presence might help new and future generations of supporters understand why the club’s history is built on substance as well as style.

While Busby fought for his life in hospital, it was Murphy who set about guiding the club through the profound tragedy that turned United into a global entity.

Twenty-three people died as a result of the plane carrying United’s team skidding off an icy runway in Munich, where it had stopped for refuelling after a European Cup quarter-final win over Red Star Belgrade. Eight of the dead were players.

It was Murphy, more than anyone, who took on the slow recovery process in those desperate times and ensured, as the song goes, that the red flag kept flying high. But he also did so much more than that. He started in the role of chief coach and, for 16 years until his retirement in 1971, was Busby’s assistant. In total, Murphy was part of the club’s fabric for a quarter of a century. He was in charge of the reserves, the youth team and the scouting division, building his reputation as a prolific discoverer of young talent.

All but three of the players who beat Benfica in the 1968 European Cup final, with Busby back at the helm, came through Murphy’s school of excellence. John Aston, David Sadler and Best were part of the team Murphy guided to his sixth FA Youth Cup triumph four years earlier.

“In my mind, nobody is more important to United’s identity and existence than Jimmy, for what he did before and after the crash,” says Wayne Barton, author of Murphy’s biography, The Man Who Kept The Red Flag Flying. “He had offers of assistance and, if he had taken them, nobody would have batted an eyelid.

“Instead he decided to stay faithful to the Busby blueprint, using grief as the driving force. He didn’t sign players en masse. The team was filled with rookies who were grieving their mates. They were playing in the memory of those who were gone. It was raw, it was real. It defined how United would be in the future. They would fight no matter how lost the cause seemed. That has defined the club in their best moments ever since.”

It certainly defined Ferguson’s teams, and perhaps that is no surprise given the story he tells about his first meeting with Murphy after taking the job in November 1986. The new manager wanted to know more about the club and why had they lapsed into years of drift. So he headed to Poynton, on the southern outskirts of Manchester, to visit Murphy at his home.

By the time he left that meeting, Ferguson had been made acutely aware how it saddened Murphy, a passionate believer in youth development, that United’s priorities had changed since his retirement 15 years earlier. Players were no longer coming through the ranks. United’s youth set-up had lost what made it special.

Ferguson came away that day knowing he had to put it right. Everything that followed – the Class of ’92, knocking a dominant Liverpool “right off their f***ing perch,” two more European Cups, 13 Premier League championships – you can join the dots all the way back to Murphy’s methodology.

At the heart of it all, there was also the human touch all the greatest football men possess. Bobby Charlton always insisted it was Murphy, rather than Busby, who did the most to shape his knowledge of the sport. Murphy, said Charlton, was “the greatest teacher of football I would know”.

Plus there was a fierce winning streak that was ideal for a club with United’s ambitions and once prompted John Doherty, part of their 1955-56 title-winning team, to describe Murphy as “a cigarette-gasping Welsh dragon who would have your guts for garters”.

David Gaskell, the youngest ever Busby Babe, recalls one dressing-room scene when he, as United’s rookie goalkeeper, had cost the reserve team an away victory at Derby County’s old Baseball Ground.

“He (Murphy) was managing the second team and, back then, we had a second team where everyone was a full international apart from me, who was only 16 or 17,” says Gaskell. “We were playing Derby County away, winning 1-0, and their centre-forward was knocking three bells out of me.

“In the last minute, he came charging at me again. So I ran out to kick the ball away and followed through with my boot to make sure I kicked the centre-forward, too. The referee blew his whistle — penalty! They scored, the game finished 1-1 and ‘Spud’ Murphy, as we called him, got hold of me after the match.

“‘Come here,’ he said, gesturing to the shower room. He had me up against the wall. ‘If you ever do anything like that again, I’ll f***ing strangle you’. When he calmed down, he had some advice for me. ‘Do it,’ he said, ‘just don’t get seen’. That summed him up in a nutshell. He was a good man.”

There were different layers, too, if you consider the stories of Murphy’s team talks before games against Leeds or Sheffield Wednesday, when he would cheerfully tell United, a Lancashire side, that footballers from the county’s bitter rival and neighbour Yorkshire were useless, even though he had Doncaster-born David Pegg and Mark Jones, a miner’s son from Barnsley, in his dressing room.

Before playing Wolves or West Bromwich Albion, Murphy might tell his players that nobody of note had ever been developed in the Midlands, despite having a footballer from Dudley in his team. And that was no ordinary player given that Murphy’s instructions, according to Duncan Edwards’ team-mates, were to “give him the f***ing ball whenever you can”.

Edwards, the original Boy Wonder, suffered devastating injuries in the Munich crash and died 15 days after. The doctors treating him in Rechts der Isar hospital reckoned it was a miracle he survived as long as he did.

He was 21, an England international with 17 caps, and one of the more poignant stories involves this juggernaut of a footballer drifting in and out of consciousness, asking Murphy for the kick-off time for United’s game against Wolves the following Saturday. With Murphy at his bedside, Edwards whispered that he was desperate not to miss it. They were his last words.

“When I used to hear Muhammad Ali proclaim to the world that he was the greatest, I used to smile,” Murphy once said. “The greatest of them all was an English footballer named Duncan Edwards.”

As for Murphy’s own strength of personality, he was not in the wreckage of British European Airways Flight 609 because, in February 1958, he was also working as the part-time manager of Wales and, on the same day as the Belgrade match, they had a World Cup qualification play-off second leg against Israel.

Murphy had permission to travel to Cardiff for that match, which meant his place on the flight to Belgrade went to Bert Whalley, United’s chief coach. Wales completed a 4-0 aggregate win and Murphy knew nothing about what had happened until he got back to Old Trafford and offered a celebratory sherry to Busby’s secretary, Alma George.

What she told him turned his life upside down. Whalley was among the dead and, for many years, Murphy was haunted by an almost immeasurable sense of guilt that it ought to have been him on the plane.

“Bert and Jimmy were like brothers,” Bobby Charlton said in Eamon Dunphy’s book, A Strange Kind Of Glory. “You never seemed to talk to one without the other. Bert would do the general things and Jimmy would pick out the young players they thought were important.”

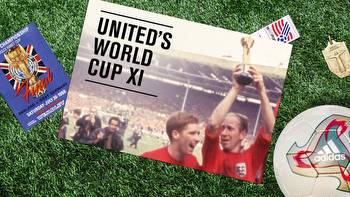

All of which makes it so extraordinary that, grief-stricken and against all the odds, Murphy led out United in an FA Cup final not even three months later, having got through three post-Munich rounds (one of them less than a fortnight after the crash and the others needing replays) to reach Wembley. They lost the game 2-0 to Bolton Wanderers but, in another sense, it was a sporting triumph built on a spirit of togetherness and competitive courage. It was the 65th anniversary on Wednesday – and no coincidence that this was the day United unveiled Murphy’s statue.

Ten years later, United were back at Wembley to play Benfica in the European Cup final. It was the holy grail for Busby’s men and, just before extra time started, Murphy was rubbing Paddy Crerand’s legs and telling the player of their Portuguese opponents: ‘Look at them, they’re shattered…”

It was true: United scored three times in those additional 30 minutes to win 4-1 against a team built around Eusebio.

But Murphy showed his human touch again at the final whistle. As the cameras focused on Busby and the victorious players, Murphy was offering his commiserations to the losing team, including a sip from his hip flask for Antonio Simoes, the Benfica winger.

“Jimmy was a very religious man,” says Barton. “After Munich, he prayed so frequently that he rubbed his crucifix down to a nub. But I don’t think it’s unfair to say he was almost as devoted to United as he was to his faith. He treated the club like family.”

Murphy, a Rhondda Valley-born former wing-half who won 15 Wales caps and made more than 200 appearances for West Brom, died in 1989, aged 79. There is a building named in his honour at United’s training ground. It is where the current manager, Erik ten Hag, usually conducts pre-match news conferences. The walls are lined with photographs, decade after decade, of the players Murphy called the “Golden Apples”.

Ten Hag has immersed himself in the club’s history since his appointment last summer, like every United manager ought to. “He (Murphy) stands for resilience and determination and they are the standards for Manchester United,” says the Dutchman. “After Munich, a manager and many players fell away. The club was devastated. They bounced back and this person played the main role. It’s totally deserved that he gets this honour.”

United had an orchard’s worth of Golden Apples during the years when Busby and Murphy created the legacy for Ferguson, Ten Hag and others to follow. And, to this day, the seeds of what Murphy helped to plant are still growing. There is a wonderful statistic, stretching back to 1937, that United have gone 4,201 games with at least one homegrown player in their matchday squad.

Manchester United’s 4,000 games of homegrown players – the legends, the one-game wonders and Fergie’s flipchart

Every member of United’s current youth team was present for yesterday’s statue unveiling. Each was wearing a suit and polished shoes, representing the modern-day club the old-fashioned way. Alex Stepney and Brian Kidd, from that 1968 European Cup winning side, pulled the ribbon to unveil the statue. Robert Page, the current Wales manager, was among the considerable guest list, along with hundreds of fans.

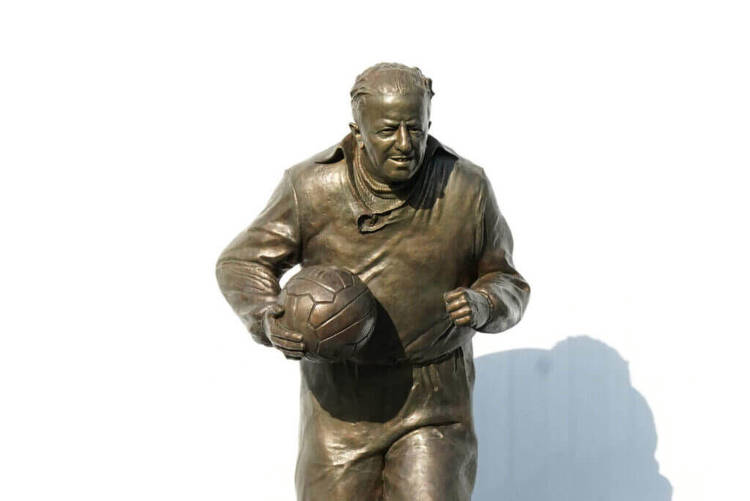

The statue shows Murphy at work – ball under arm, leaning in, giving instructions – and the Stretford End was chosen for its location because it overlooks the cinder pitches where he used to train the Busby Babes.

Jim Murphy Jr still goes into the academy to watch their matches and maintain the family’s links with the club. His father, he said, had offers to leave United, then a broken football club, in 1958. One was to become the manager of Arsenal. Another was from Juventus. The third was a coaching role with Brazil, who had just won the World Cup with some kid called Pele in their side. Murphy turned down all three. His love for United was too strong.

“If you can imagine what would happen today with the Munich air crash, the support my father would have had, the counselling – he didn’t have any of that,” Jim told the crowd who had gathered in the early-evening sunshine. “What he had was a strong wife (Winnie) and a family. And a resolve to get on with the job.

“The board of directors wanted the club to drop out of the league that season. My dad said, ‘No, there’s a job here and I can do it’. And that’s what he did.”