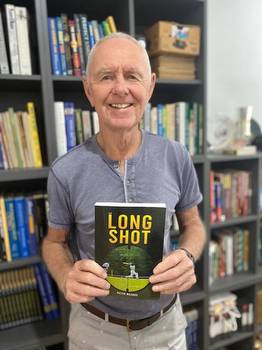

Michael Coward appointed a Member of the Order of Australia

Undeniably one of the characters of cricket is long-time journalist and historian Michael Coward.

His passion for the gentleman’s game is evident in all his work, and his honest and insightful words are a timeless reminder of the purity of the sport.

“The industry has changed very dramatically, since I started in 1963,” he said.

“Cricket was for me a love as a boy, and then I was fortunate as I grew into the industry that I was able to spend time doing something that a lot of people would like to do — watching cricket and football.”

Mr Coward’s love and passion for the sport brought him into journalism, but he said the lessons about humanity he has learned through his career are ones that will stay for him longer than the matches.

“I’ve always been interested in the anthropology of the game,” he said. “I’m fascinated more (or as much) by the people who play it than of the game itself.

“Henry Olonga — the Zimbabwean fast bowler who defied Mugabe with the black armband protest in 2003 at the World Cup. I mean the courage of the man to do that.

“Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene — the leadership they brought to the game in Sri Lanka at the time that Sri Lanka was at war, and they played on and with such enormous courage.

“I think sometimes people forget the impact the game has in a society, and particularly in a society that is struggling.”

A cricket purist, Mr Coward is dubious of the changing nature of the game. He has been appointed a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to the sport he loves, and his work at recording its significance forever.

“I’m not a mad fan (of twenty20 cricket),” he said. “Anything that involves the kids in cricket and gives them a knowledge of cricket is fantastic, but the thing that worries me is that twenty20 has monopolised the conversation.

“And night Test cricket; obviously as a traditionalist I want Test cricket to survive. ”

15 minutes with Michael Coward

Where did your love of cricket come from, and how did you get into sports journalism?

As a boy I loved it. I always loved the cricket and Australian football, growing up in Adelaide. I was just passionate about it. And then when I got into journalism, very young at 17, I always wanted to be a sports writer but the best advice I ever had was from my mentor who said ‘be a journalist before you’re a sports writer’. And that was very good advice, so I did police rounds and court reporting, and everything. And it was tremendously positive training towards being a sports writer. Of course the industry has changed very dramatically, I started in 1963; so 53 years is a long time and it’s changed very dramatically. So that’s how it all started, a love as a boy and then I was fortunate as I grew into the industry to that I was able to spend time doing something that a lot of people would like to do — watching cricket and football.

Tell me more about those earlier years?

I didn’t really specialise in cricket for quite some time. I worked for years in Adelaide and Melbourne, and then went to London for three years with AAP — and that was my first cricket tour — (Greg) Chapell’s tour of England in 1972. And then I came back to Adelaide for the , and became the chief cricket writer at the in the mid ‘70s, and then worked on the Age, and then came here to be the Sydney Morning Herald cricket writer in 1984 and did five years for them which was thoroughly enjoyable but exhausting because I did every game that Australia played from August ‘84 to March ‘89, and that was very solid. Sadly I didn’t go to England for ‘89 when they regained the Ashes, but after that I’ve worked as a freelancer since then, and worked at the Australian for 20 years as their columnist.

What were some of your most memorable matches to report on?

Clearly the tied test in 1986 in Chennai, which was Chennai but is now Chennai in India. There’s only ben two tied Test matches in history, and to be there for that one was just a privilege, it was just extraordinary. So, that, and the World Cup in 87 — Australia’s first World Cup against the odds 16-1 — that was in India as well. In Kolkata. That was thrilling, both of these teams were led by Alan Border who I have the most enormous admiration for. Because he virtually single-handedly rebuilt Australian cricket. I’ve been very fortunate, I’ve covered cricket all over the world — India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Kenya, South Africa, Zimbabwe — everywhere they play it really. So I’ve been very fortunate. I wrote books in the Caribbean, books in South Africa and one thing or another. But those two events are the two for me — and I’ve got a love of India, a fascination for India, so I may be a tad biased. But they were very special events.

You mentioned Alan Border, which other players in your time of covering cricket have been real game changers for the sport?

There’s so many that you respect for different reasons as cricketers. I’ve always been interested in the anthropology of the game. I’m fascinated more (or as much) by the people who play it than of the game itself. And you see it in its social and cultural context.

Henry Olonga — the Zimbabwean fast bowler who defied Mugabe with the black armband protest in 2003 at the World Cup. I mean the courage of the man to do that. He’s living in Adelaide now incidentally.

Kumar Sangakkara and Mahela Jayawardene — the leadership they brought to the game in Sri Lanka at the time that Sri Lanka was at war, and they played on and with such enormous courage. I think sometimes people forget the impact the game has in a society, and particularly in a society that is struggling. People identify with the cricketers and with sports because its an outlet for them.

And it’s a very powerful outlet, I mean you just have to look at South Africa in 1994. Australia played there for the first time since 1970. Months before the first election; after Mandela was released from jail; and the build up to the election and the tension in the country leading up to the election. Many were thrilled that it was happening, and other (particularly the whites) thought a revolution was imminent. So to find the game, in the midst of all these things is thrilling.

You’ve lived through some amazing experiences, so what do you think of the shape of the modern game, and the direction cricket’s heading now (in particular 20/20 cricket)?

I’m not a mad fan (of 20/20 cricket). It’s a delicate subject. Anything that involves the kids in cricket and gives them a knowledge of cricket is fantastic. But the thing that worries me is that the 20/20 has monopolised the conversation of the game. That’s all anyone talks about now 20/20. And night Test cricket: obviously as a traditionalist I want Test cricket to survive, and I’m as uneasy as some of the players are about the night matches because of the colour of the ball and other issues. It’s interesting that both Steve Smith and Alistair Cook (last week) the England captain have said no night cricket for the Ashes Series in 17-18, which is really interesting. It was very funny looking at Steve Smith, trying to look enthusiastic about South Africa’s decision to play the Test match at night at Adelaide in November. He was absolutely deadpan serious, and as you know it’s quite obvious the Australians don’t agree with it and they're not totally comfortable with it. But they’ve been directed to by the Board, and so it was very funny watching it on television when he was trying to look enthusiastic. So that’s my one concern. It monopolises the conversation of the game and the history of the game and the richness of the game in its history and traditions, I mean there’s art, and literacy and poetry, and everything and everything else is forced into the background, and that worries me a lot. The game is rich in its history, and there's no other game like it and we don’t want to lose that. The game has always evolved to suit the community, and that’s where its been a very smart sport. But I’d heed don’t forget what’s gone before.

Indeed. And, would you say that in your eyes modern journalism has also taken some similar turns as cricket has, and perhaps forgotten the traditional aspects in lieu of social media and new-age journalism?

Definitely, You’re very right. I mean I had a very tough training in agencies and afternoon papers because deadline was every split second, so I know exactly what you have to confront with today. One of the sadnesses I think is that the quality is suffering because of the speed. The reduction in the number of staff, and things like this is putting enormous pressure on the staff, There’s no doubt about that. I’ve always said that no one should be penalised for their passions, and that if they’re keen enough and passionate enough, they can still make a go of it. But I’m finding it harder to say that to kids who ask you what of the future, what should I do And that’s really sad, but it’s the way society is going.

The award you’re being honoured with is for your service to journalism, how proud or humble are you to be receiving it?

It’s very overwhelming. But its recognition, I like to think, for the significance of cricket writing. And cricket journalism. And recognition of the significance of cricket in society. The joy that it brings to so many people year in and year out, and always has, and hopefully always will. And that’s what I feel the award recognises, and that’s exciting.

What’s life away from the cricket look like for you — I heard you could sing a bit and turn some heads at parties?

I did sing a lot when I was young, and still sing a bit, but usually after a few too many white wines. I’ve always loved music, and show music. That’s one of my great interests along with bushwalking, which I’m doing more of in recent years. I did the Milford trek in New Zealand, did Machu Picchu a few years ago — with one of my Godsons which was terrific, and we did the Nakasendo in Japan last year — so I’m enjoying those sort of things as the intensity of life goes a bit. I’m still working at the Bradman Museum and International Cricket Hall of Fame at Bowral, which is really enjoyable because I’m doing a lot of the archival work there. Archival interviews and the like, and we’ve got over 110 interviews in the can, of which I’ve done about 90, and so I’ve been very fortunate to have sat down with the greatest cricketers of the last 60-70 years I suppose. Since I've started, I think about 16 have died, which just goes to show the importance of recording and reporting. And, sadly, that list includes Philip Hughes and Richie Benaud and those that have gone in recent times. But it’s a very satisfying way to finish a long working life is to be involved with the history of the game and helping to make sure it is preserved.