MLB players used to catch balls thrown from Washington Monument

On Dec. 6, 1884, in a ceremony that lasted 15 minutes, the aluminum capstone was placed atop the Washington Monument. A cannon fired to celebrate the completion of the structure, which had been in construction since 1848 and, standing 555 feet, was the tallest built by human hands. Later that month, P.H. McLaughlin, who oversaw the building of the stone obelisk, bet Providence Grays outfielder and Virginia native Paul Hines that he couldn’t catch a baseball tossed from one of the windows near the top.

“The ball, it is thought, would not be going as fast as many that are taken readily by the infielders in a game of ball, but there are other matters to be considered which would make the test more difficult,” the Washington Evening Star posited in a story about McLaughlin’s wager. “If Hines should attempt to catch it, he would probably have more trouble judging it than catching it.”

On Jan. 8, 1885, more than a month before the Washington Monument was officially dedicated and three years before it opened to the public, Hines and “several well-known ball tossers,” including Phil Baker and Ed Yewell of the Washington Nationals, became the first men to attempt to catch a baseball dropped from the structure’s 505-foot observation level. Their failure inspired others to try.

Over the ensuing decades, dozens of ballplayers attempted the feat. The first successful catch, in 1908, sparked subsequent bouts of one-upmanship from even taller structures and similar stunts involving baseballs dropped from airplanes and blimps — with occasionally painful results.

Every year after the Washington Monument’s completion, Chicago Colts player-manager Cap Anson and H.P. Burney, the chief clerk of the Arlington Hotel, where the National League club stayed when it came to D.C., would engage in a debate about whether it was possible to catch a baseball dropped from the top of the structure. Several players, including Boston Beaneaters outfielders Marty Sullivan and Steve Brodie, had failed after Hines’s initial ill-fated try.

“Burney was wont to affirm that no baseballist on earth ever had or ever could catch a regulation ball that was tossed from one of the windows of the Washington Monument,” The Washington Post reported in August 1894, with the Colts in town for a three-game set. “Had not Paul Hines tried it in days of yore with dire failure? And Paul was no slouch.”

Before the second game of the series, Chicago catcher William “Pop” Schriver and a few teammates, including pitcher Clark Griffith, made their way to the Washington Monument’s grounds. The Post reported that Schriver watched the first ball dropped by Griffith hit the ground and was surprised to see it bounce rather than bore a hole in the turf.

“This encouraged Schriver wonderfully, and he resolved that the catch was no great shakes after all,” The Post reported. “The signal was given from above and again the ball was pitched forth, Schriver catching it fair and square, amid the applause of the spectators. … He didn’t get a chance to repeat the act, for by this time the monument cop got on to the game and was highly indignant that any such affair had occurred. He talked of arrests but was finally talked into a more amiable temper and the party came up town joyously with Billy Schriver a hero.”

Griffith — the future Washington Senators player, manager and owner — would later dispute this account, saying the second ball he dropped landed in Schriver’s mitt but popped out. By 1906, when Hines recounted his unsuccessful 1885 attempt in The Post, Schriver’s catch was no longer recognized as legitimate.

“I have no doubt that the feat of catching a thrown ball from the top of the Monument can be accomplished, but it should be thrown out from it, and the ball ought to be black,” Hines, who didn’t use a glove for his attempts, told The Post. “The balls thrown to me were new, white ones, and it was hard to distinguish them from the white background of the Monument. … I doubt if this will ever be done, for soon after I tried it a law was passed making it illegal to throw from the Monument, and one who does it is subject to arrest and a fine of $500.”

In 1908, D.C. socialite Preston Gibson bet Senators fan John Biddle $500 that Charles “Gabby” Street, Senators pitcher Walter Johnson’s personal catcher, could catch a baseball dropped from the top of the Washington Monument. Not wanting to risk a fine — or worse — Gibson secured a permit from the superintendent of public buildings and grounds, and he turned Street’s attempt into a public spectacle. Senators shortstop George McBride and outfielder Bob Ganley attended, along with a photographer from The Post.

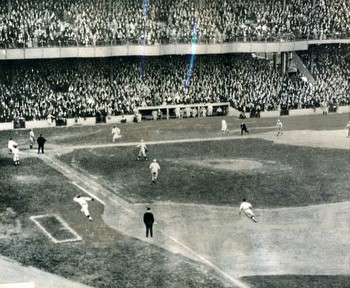

On Aug. 21, with a crowd of spectators gathered below, Gibson rolled 10 balls down a wooden chute and out the window of the monument, but they all bounced off the obelisk’s side or landed too close to the base for Street to get in position to make a catch. Gibson ditched the chute and started throwing the baseballs instead.

“The thirteenth ball was the lucky number, for this Street got under and held tightly in his great mitt,” The Post reported. “… The speed at which it traveled was about an eighth as fast as a rifle bullet, and if it had not been for the very scientific way in which Street caught the ball it would undoubtedly have broken his arm. As it was, it almost carried him to the ground, so great was its impact, and those who stood in the window of the Monument heard a report like the shot of a pistol when it struck his glove.”

The crowd “greeted the wonderful stunt with a cheer that made ripples on the Potomac” as Street, wearing slacks, a dress shirt and a dark tie, held the ball from his historic grab aloft.

“Gee, I’m glad you weren’t hurt,” a young boy who watched the feat from the top of the monument told Street, who played four seasons for Washington and later went on to manage the St. Louis Cardinals to the 1931 World Series title. “Talk about bravery. You make these war correspondents that write about themselves look like pikers.”

The Senators defeated the Detroit Tigers, 3-1, later that day, with Street behind the plate for Johnson’s five-hitter. Five days later, Street broke his finger on a foul tip.

Gibson kept the ball from Street’s monumental catch. It was a National League ball, despite the fact that the Senators played in the American League, and inscribed as follows: August 21, 1908, 11:30 a.m. Dropped from the Washington Monument by W.J. Preston Gibson, caught by Gabby Street. 550 feet, 135 feet per second.

James McMillan Gibson came across the ball after his father died in 1937. It resurfaced among his belongings when he and his wife sold their Georgetown mansion to former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1964. He later donated it to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

On Aug. 24, 1910, Chicago White Sox catcher Billy Sullivan caught three of 11 balls dropped from the top of the Washington Monument by pitchers Ed Walsh and Doc White, setting a “record for freak baseball feats,” according to The Post.

The Washington Monument was conquered, but baseball-catching stunts continued.

In March 1915, while his Brooklyn Robins were training in Daytona, Fla., Manager Wilbert Robinson attempted to catch a baseball dropped from an airplane by the team’s trainer, Frank Kelly. Except rather than a baseball, Kelly dropped a grapefruit, which was rumored to have been given to him by Brooklyn’s resident prankster, 26-year-old outfielder Casey Stengel. The grapefruit hit Robinson on the shoulder and knocked him flat on his back.

“The players are laughing yet over the stunt,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported. “It seems that Robbie thought the missile was a baseball, and insisted on showing the gang how he used to catch a ball in old Oriole days, when the fruit struck him and spattered him all over, and he thought he was mortally wounded, and insisted that the juice was blood. … It will be several years before the manager lives down his nickname of Grapefruit Robbie.”

Babe Ruth wasn’t above such high jinks. In July 1926, as part of a publicity stunt for the Citizens’ Military Training Camps, the Great Bambino attempted to catch a ball dropped an estimated 300 feet from an airplane at Mitchel Field on Long Island. Dressed in army garb, Ruth was successful on his seventh try.

“Ruth was darting about the field under the blistering sun, getting hotter and hotter,” the New York Times reported. “The only breeze was the twisters kicked up by the plane which sent tornadoes of dust about the baseball hero. The officers congratulated him, and said if there should be another war and New York should be bombed they would have Ruth assigned to defense work, catching enemy bombs.”

On April 1, 1930, Chicago Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett caught a baseball dropped from a Goodyear blimp flying an estimated 800 feet above Los Angeles. In 1938, Cleveland Indians catchers Frankie Pytlak and Hank Helf each snagged a ball thrown by rookie third baseman Ken Keltner from the top of Cleveland’s Terminal Tower, about 708 feet above the city’s public square.

“Police estimated that 10,000 persons thronged roped-off areas around the square’s southeast quadrant, where the catchers stood, and that another 5,000 peered from windows in office buildings to watch the record-shattering pitching stunt,” UPI reported. “… The catchers wore steel miner’s helmets after the practice throws. Helf, jerking himself into position as the second official ball sped crazily to earth, caught it with his outstretched mitt.”

“There was nothin’ to it,” Helf said. “I just kept my eye on the ball all the way down. It didn’t come any harder than a fast pitch.”

On May 10, 1939, Dave Coble and three of his Phillies teammates, including fellow catcher Walter Millies, donned football helmets as they attempted to catch baseballs thrown 521 feet from the top of Philadelphia’s William Penn Tower. Coble, a 26-year-old rookie, was the only player to make a clean catch.

“After four attempts,” Coble recalled years later, “Millies handed me the mitt and said: ‘Here, I’m married and got children. You’re single. I’m quitting.’ ”

On the same day as Coble’s catch, Hall of Famer Lefty O’Doul, manager of the Pacific Coast League’s San Francisco Seals, climbed to the top of the 437-foot Tower of the Sun at the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco and dropped baseballs to three of his players waiting below. After catcher Joe Sprinz caught one of his throws, O’Doul announced, “There’ll be no more of that sort of thing.”

Sprinz should have heeded his manager’s advice. Instead, he attempted to make history on his 37th birthday.

“Joe Sprinz is in a hospital with his face held together with surgical wire, because he tried to catch a baseball falling at a speed of 145 miles an hour — and failed,” UPI reported Aug. 3, 1939. “Sprinz was seeking to establish one of those mythical records by catching a baseball dropped 800 feet from a blimp cruising over the sports field at the San Francisco exposition. He was under the ball, all right, but it crashed through his upraised hands and struck him full in the face, with an impact estimated at 8,050 foot pounds. The blow gave him a compound fracture of the upper jaw, broke eight teeth and left ragged lacerations about his lips. Doctors said he will be in the hospital for two weeks while his face is restored and probably will be out of action for a month. President Charles Graham of the Seals said: No more stunts.”

Perhaps it’s no surprise that such experiments, at least by professional ballplayers, fell out of fashion in subsequent years. In 1945, Street was working as the Cardinals’ radio broadcaster when he reenacted his historic feat as part of a Griesedieck Brewery-sponsored promotion to raise money for war bonds. The 63-year-old caught two of four balls dropped by his 31-year-old broadcast partner, Harry Caray, from the top of St. Louis’s 387-foot Civil Courts Building.

“Those were my greatest catches, greater than the Monument,” Street said, according to Tim Wiles, former director of research for the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Though it didn’t involve a player, officials of the Seattle World’s Fair called off a stunt in 1962 that would have involved Sal Durante, the fan who caught Roger Maris’s 61st home run the previous year, attempting to catch a ball from the Space Needle. (A University of Washington physicist estimated the ball would be traveling 130 mph when it reached the bottom of its 600-foot drop.)

In 1974, Fleer released a “Baseball’s Wildest Days and Plays” trading card set, featuring illustrations by cartoonist Robert Laughlin. One of the cards commemorates Street’s Washington Monument catch. Mike Litterst, chief of communications for the National Mall and Memorial Parks, keeps that card, which depicts Street in uniform rather than street clothes, pinned to the bulletin board in his office.

Litterst, a Nationals fan, said the monument’s eight observation windows are rarely opened anymore, and it was a major production requiring multiple people to open a single window for a photograph a few years ago. He agreed Keibert Ruiz catching a baseball thrown from the top of the Washington Monument by Nationals teammate CJ Abrams would make for terrific content but doesn’t imagine Street’s feat will be attempted again any time soon.

“If I’m the management of the Nats,” he said with a laugh, “I’m not risking it.”