Other Boston franchise owners already have a place in their Halls of Fame

Robert Kraft would hardly be the first Boston pro sports franchise owner to be inducted into a Hall of Fame.

In point of fact, all three other franchises - the Red Sox, Celtics and Bruins -- can all lay claim to having owners represented in their respective Halls.

Kraft is hardly guaranteed election into Canton, but he was recently named a finalist, with the vote scheduled Aug. 15.

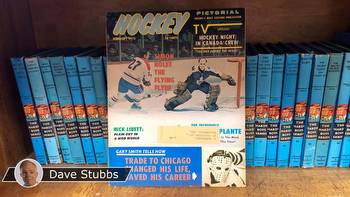

The most recent inductee was Jeremy Jacobs, who has owned the Bruins since 1975. Jacobs has also served as the chairman of the NHL’s Board of Governors since 2007 and has long been viewed as one of the league’s most powerful owners.

In the past, he took an active role in the league’s labor negotiations with the NHL Players Association and for years was known as one of the more hard-line labor hawks when it came to dealing with the union.

Prior to the implementation of the salary cap, Jacobs made sure that the Bruins had one of the smallest payrolls in the league. Since the cap was introduced and presented him with cap certainty, the Bruins have spent more liberally and, generally, been more successful on the ice. In the past decade, the Bruins have been to the Stanley Cup Final on three occasions.

21+ and present in participating states. Gambling problem? Call 1-800-Gambler.But, in part because Jacobs ran a tight financial ship with his club, the Bruins failed to win a Stanley Cup on his watch from 1975 until 2011, a period of 36 years. Their previous last Cup came in 1972.

If an owner is ultimately judged by how much his team has won, then Jacobs place in the Hall can be debated. But because other factors are considered, including tougher-to-quantify intangibles like power, influence and impact — to say nothing of longevity — Jacobs was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2017.

Former Celtics owner Walter Brown holds the dual distinction of being enshrined into both the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield and the the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto.

Brown actually began his career in hockey, serving as a coach of the amateur Boston Olympics while also guiding the U.S. to its first gold medal in the Ice Hockey World Championships. In 1951, he bought the Bruins, giving him ownership of both Boston winter sports teams, having founded the Celtics the previous year.

Prior to his death in 1964, he oversaw the start of the Celtics’ dynastic run, as they won six NBA titles in the span of seven years. He also hired Red Auerbach and gave him the responsibility of being the team’s coach and GM. The Celtics would go on to win 11 championships in 13 years, largely based on the foundation he oversaw.

Brown didn’t live long enough to witness the Celtics dynasty in full bloom. But as the original owner and founder of a franchise that became synonymous with both the sport and the NBA, his contributions and worthiness are undeniable.

When he died in 1964, the NBA named its championship trophy after him. (It has subsequently been renamed the Larry O’Brien Trophy). He was elected to the Basketball Hall a year after his passing.

The most controversial owner of the group is former Red Sox owner Thomas A. Yawkey.

Yawkey, who was born in Michigan but spent much of early life in South Carolina, purchased the Sox in 1933 and remained the team’s sole owner until he died in 1976 from leukemia. After his passing, his widow, Jean, and later his estate, retained ownership of the franchise until February 2002.

Yawkey purchased the Sox for $1.25 million, when he was just 30 years old, having come into a substantial inheritance. He also made improvements to Fenway Park, which was just over 20 years old when he first bought the team.

In his 44 years of ownership, the Red Sox won three pennants (1946, 1967 and 1975), but could never win a championship while Yawkey was alive. In fact, the Sox didn’t win a World Series and end an 86-year drought until 2004, 28 years after he died and two years after his estate sold the team and the ballpark to a group headed by John Henry.

Yawkey was known for his philanthropy, having made the Jimmy Fund the team’s official charity while, for a time, serving as the chairman of the board of trustees. To this day, the Yawkey Foundation, carrying his name, continues as a philanthropic force in the city of Boston and the surrounding area.

But his legacy is, to say the least, a complicated one.

Under Yawkey, the Red Sox were the last MLB franchise to integrate, with Pumpsie Green becoming the team’s first Black player in 1959. Remarkably, the Bruins employed a Black player before the Red Sox did.

There exists contradictory evidence as to whether Yawkey himself was a racist. No less an authority than Jackie Robinson, who once was given a sham tryout by the Red Sox, was convinced he was. (Ironically, the Yawkey Foundation has long been a benefactor for the Jackie Robinson Museum in New York).

Others — including former Red Sox outfielder Reggie Smith — have gone on record to say that they were treated well by Yawkey and saw no examples of racism in their interactions with him.

Still, the current ownership group, led by Henry, was so troubled by the specter of Yawkey’s legacy that they moved to change the name of the street on which Fenway was built from Yawkey Way to its original name, Jersey Street, in 2018.

For his longstanding involvement in the game, his ownership of a charter franchise and his service as vice president of the American League in 1980, Yawkey was inducted into Cooperstown in 1980.

Kraft could close the circle and give all four teams a representative in their respective Halls. But as with most of the other owners representing Boston, there is some controversy attached to his candidacy.