Sandro Tonali’s gambling did not pay dividends

Far too often, football is the victim of its own brazen, naked hypocrisy. As monetisation, greed and hyper-capitalism have taken a stranglehold of football, morals have flown out of the window. Money pours in from malevolent sources – the authorities do not seek to temper this evolution; rather, they actively encourage it.

Saudi Arabia, as a pertinent example, has taken advantage of this mindset, using football as a tool through which to sportswash its government – FIFA provided the nation with an open goal to host the 2034 World Cup, Newcastle United have surged up the table backed by PIF ownership, whilst the Saudi Pro League has seen an influx of high-profile stars hypnotised by eye-watering pay packets. Jordan Henderson, once an outspoken ally on LGBTQ+ issues, now works for employers that actively criminalise homosexuality.

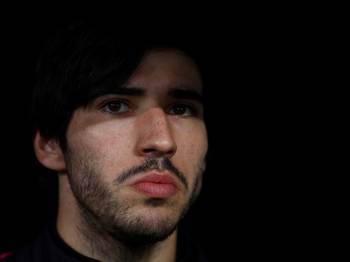

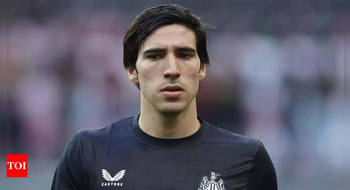

Money may not quite be the root of all evil, but it encourages authorities to turn a blind eye. This shameless hypocrisy has been further highlighted in recent weeks through an investigation into betting within Italian football. Sandro Tonali, Newcastle United’s £50million headline summer signing, has been banned for ten months for illegal gambling activities in his native country.

Tonali is reported to have bet on his previous side, AC Milan, to win games, as well as having used illegal gambling websites. He will not play for the Magpies again this season, and nor will he participate in this year’s Euros. For Tonali and Newcastle, it is a crushing a blow. For the club, it leaves a gaping hole in a team already stretched thin by injuries and fixture list pressures. On a personal level, it stalls the career of a young star.

The footballing authorities have come down hard on Tonali, exercising the strict punishments linked to gambling transgressions. His ban also entails an additional 8-month suspended sentence, a comprehensive rehabilitation programme and over 16 visits to Italy to inform young players of the dangers associated with betting.

It is a story lathered in rich irony. Tonali is not the first player to succumb to temptations and break regulations – Ivan Toney was banned for eight months for 232 breaks of the FA’s betting rules last spring, whilst Paul Merson’s public addiction troubles saw him lose £7million.

When players break the rules, they are publicly shamed and castigated, banned for long periods of time and earn an uncomfortable reputation. Yet football remains comfortable in bathing in the gambling industry’s investment, sponsorship, and support. It’s an uncomfortable paradox. In the 2020-21 season, football received £500million from gambling advertisements and sponsorships alone. The English Football League is sponsored by SkyBet. Even Newcastle United, Tonali’s employer, have three betting companies as major partners.

Football and gambling are inextricably linked. This marriage means that players themselves are de facto walking advertisements for gambling – it has been recorded that during some matches the logos of gambling companies can be spotted over 700 times. Embedded in a sport dependent on gambling, it is inevitable that some players will not be able to resist taking part. Footballers are ultimately humans too, susceptible to the same temptations and vulnerabilities as everyone else.

Players such as Tonali are addicts suffering from an illness and should be treated as such – in England alone, there are over 400 suicides a year linked to problem gambling. Focus should not be on undue, excessive punishment, seeking to make an example of someone suffering. Rather, emphasis should be placed on rehabilitation, assessing that a gambler is not evil nor bad, but ill and in need of support. Footballing authorities should be eager to offer that support – anything less would be a shameless, hypocritical dereliction of duty.

As such, football needs to seriously re-assess its own relationship with gambling. Research has shown that professional footballers are three times more likely to have gambling problems; meanwhile, in the last two years over 150 footballers have undergone treatment for addiction, according to Sporting Chance, the addiction clinic set up by ex-footballer Tony Adams.

It poses a powerful dilemma – for all the money that the gambling industry brings to football, is it worth it? Is it worth the addictions, the mental health crises, and individual financial problems? Is it worth the valid accusations of hypocrisy and moral bankruptcy? When footballers such as Tonali receive life-changing bans, but football continues to encourage those very same behaviours, moral questions have to be asked.