Speed Figures: Aussie Duo Strives To Simplify The Racing Form

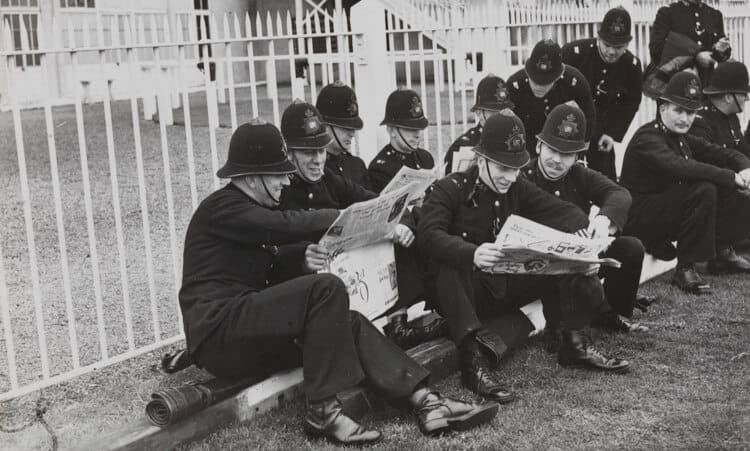

Say you’re a guy who grew up around horse racing. Your dad took you to the track when you were young, slowly but surely explaining the ins and outs of not only the sport, but how to handicap a race.

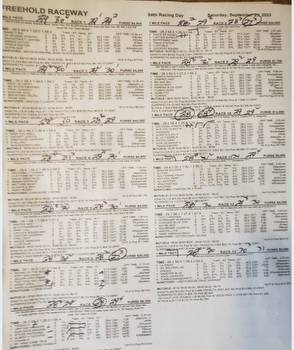

By the time you were old enough to place a wager, you knew exactly what to say and in what order when you arrived at the teller’s window. Gradually, you learned how to decipher past performances and other bits of information contained in the Daily Racing Form.

Like your dad, you became hooked on the sport — not only for its beauty, but for the intellectual patience it took to bet on it properly. A horse race wasn’t just a spin at the roulette wheel; it was a puzzle to be solved, a safe to be cracked — and the more information, the merrier.

You reach your mid-20s and meet a woman (we’ll call her Paula) you feel like you could share your life with. Better yet, she owns a horse, stabling it about an hour’s drive from town. You visit the horse — its name is Butters — and your love for this woman, and the horse, deepens.

You’ve developed an appreciation for the way in which Paula loves horses, and now you want her to reciprocate. She’s never been to a horse race, you come to find out, so you set a date for a Saturday afternoon outing to your local racetrack.

Paula is charmed by the setting, but she’s never placed a bet. You buy her a copy of the DRF. She stares at the figures, grinning but lost.

“So, what do all these numbers mean?” she asks.

Before you start to explain, you think to yourself, This could take all day. In fact, it could take more than a day. This sort of hard-earned acumen was part of what appealed to you about horse betting as a young lad, but it’s also precisely what’s so unappealing to countless others who come to the sport later in life and have less appreciation for its pedigree.

It seems like an impossible gap to bridge, but that’s not stopping a pair of Australians from trying.

The distillation process

As with stock trading and sports betting, there are major market movers in horse racing. Some are computer-proficient global syndicates that rely on the wiles of people like David Walsh, an Australian who, along with his partners, won $17 million on the 2009 Melbourne Cup card alone.

Luke Byrne and Paul Griffin are both great admirers of Walsh. But when the Perth-based duo developed their own algorithm in an attempt to mimic what Walsh was doing, “it didn’t work,” said Griffin.

While perhaps it didn’t work in the grandiose sense that Byrne and Griffin had envisioned, all was not lost.

“What we did realize is our ratings are pretty decent and they provide a tool for the punter,” said Griffin.

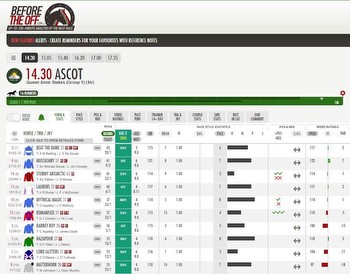

The pair’s ratings involve a computerized compression of all the data points you might find in the DRF, arriving at a single number that represents what a horse’s true morning-line odds should be. Or, as Byrne puts it, “What does a machine-learning algorithm think about a horse’s chances in a race?”

“I can’t read forms, but the reason why I built it is it can distill a form down to a number,” said Griffin. “[The] form is the biggest barrier of entry for people to be introduced to the racing industry. If you simplify it, it makes it a lot easier to look at a race. It’s a very quick way of deciphering form in a quick period of time.”

Byrne and Griffin have taken their ratings and packaged them as a B2B product called Nostradamus that is currently being tested with data from racetracks in Hong Kong and Australia. The pair would love to find a U.S. partner, but that quest has thus far proven cost-prohibitive due to the fees associated with statistical access.

Often, the rating assigned to a horse by Nostradamus will align with its betting odds in a given race. But other times, there is a noticeable disparity between the two figures, indicating that a market mover like Walsh may know something about a horse that the betting public doesn’t, or that there’s some sort of mass emotional reaction to a horse that is skewing things.

“The gap between the odds and that [rating] is the ephemeral, missing information,” explained Griffin, who takes pride in the fact that the Nostradamus rating “doesn’t hold any emotion, as opposed to the parimutuel market, which is emotion-driven.”

‘People expect a lot more from the sport’

Back at the track with Paula, you’re at a loss for words. You want to wax poetic about what every last number in the form in front of her means, but it’s all so complicated. If only she could literally talk to the form, and the form could talk back.

Enter Byrne and Griffin’s AI chatbot, which they’ve dubbed Copilot.

Let’s say you want to bet a Pick Four with three horses per race, with one in each race being a short-priced favorite, then a longshot that tends to run well on yielding turf, and finally a mid-priced colt with a top jockey aboard. Through either a single question or a series of shorter queries, Copilot’s users will essentially be able to have this conversation with the virtual form, which would result in a plug-and-play bet slip.

Yes, some bettors may like to pore through the form and handpick this information for themselves, and they may not mind that this takes a little time. But for bettors uninterested in such tedium, Copilot may be a neat trick for pushing previously intimidated folks into the parimutuel pool.

“People are going to expect this kind of ability pretty much from everything, in the same way that when you search on a website, you expect a Google-level search,” explained Griffin. “Historical technology has suited racing for 100 years, but we’re transitioning to a future where people expect a lot more from the sport.

“Racing needs to choose between servicing an emerging digital native generation of users appropriately or suffer a rapid decline of engagement. Racing as a sport will never change, but the dynamics and expectations around the audience will.”