The Premier League’s camp for de-selected players: ‘Being released does not define them’

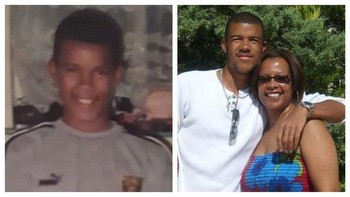

Wes Morgan can hardly believe how his career turned out.

At the age of 32, he led Leicester City to their Premier League title. At 37, he lifted the FA Cup as their captain at Wembley. Now, aged 39, he is enjoying a well-earned retirement. But before he got to receive those trophies, the former Jamaica international endured his fair share of difficult moments, none greater than being released by Notts County as a 15-year-old.

“I didn’t get a youth-team contract,” Morgan tells The Athletic. “It was hard to face that rejection. There was nothing like what the Premier League have provided today.”

He is referring to the Premier League Preparation Programme, an annual camp at Loughborough University, just north of Leicester, to assist players aged 16-21 who have not been retained by their clubs’ academies.

Morgan was invited to the camp because of what he experienced in the professional game, to offer advice and lead sessions for the young attendees. “The onus was on me to motivate myself and deal with the disappointment,” he says. “That is why these camps are fantastic. It can be difficult for kids, facing rejection and not having a backup.”

A 2022 Premier League study revealed that 97 per cent of players at top academies never play a minute of top-flight football. Another — from Football Family, a non-profit organisation for those who need help in such situations — showed more than 11,000 players aged between eight and 18 are released from academy football every year.

Rejection can be agony for the young footballers concerned, who often have tunnel vision when it comes to their futures and their ambitions to earn a career in the game. They work strenuously every day, their success dependent on someone in authority giving them a chance, but then, in an instant, their hope vanishes.

GO DEEPER

The EPPP - 10 years on: Has it transformed English football for the better?

That subsequent feeling of loneliness and how detrimental it can be to a young player’s mental health is something that David Rainford, the Premier League’s head of education and academy player care, talks about at the camp.

“Mental health is a fundamental part of our programme,” Rainford says. “Being released, or de-selected, is tough. It is a setback. We want to give them some context: that it does not define them. It is just part of the football journey. Football is not linear. Leaving a club is, for a lot of players, part of their football journey. Sometimes just showing them that they are part of a wider family of football, where this does happen, can help them get confidence in themselves — that they will come back from that.

“Here, we have 42 players who are all in that position. It is a bit of a community and helps our boys know that they are not the only ones going through this.”

On the day The Athletic visits the camp, the mood among the coaches is upbeat despite the wet weather, with the players finishing off drills and small-sided games in the rain. Loughborough’s 523-acre campus includes several football pitches, as well as sports halls and artificial surfaces. Its range of training facilities would not look out of place at the majority of Premier League training grounds.

The coaches wear blue jackets with Premier League branding, while some of the players are in the shirts of the clubs they recently left. After this outdoor session, everyone goes inside to have lunch before the seminars begin. In what has to be a tough time for any young footballer, being able to continue to train, eat, laugh and learn alongside their peers who share their anguish seems to be appreciated.

GO DEEPER

'Where do they go? Who's helping them?' - Steven Caulker's academy for released players

The camp is open to any player between the ages of 16 and 21 who has been released and not signed a professional contract. They stay for a week, making use of the university’s student accommodation, which means they properly get the chance to bond. During their time at the camp, they have a schedule of breakfast, training during the day, and then workshops and seminars right through the week.

This is the sixth time the camp has been held. This year, the Premier League expanded its support to players who have fallen out of the professional game in the last three years, aiming to ensure they have all received the help they might need, including elite performance training, recruitment options, career and education guidance, tailored one-to-one plans and the chance to hear from and talk to special guests from within the industry.

Kelechi Etienne, a 19-year-old from north London who is without a club after being let go by Fulham of the Premier League and League One’s Shrewsbury Town, told The Athletic: “It has helped me remind myself not to give up and that there will always be opportunities around the corner.”

One of the players who benefited from the camp in the past and found future chances in the game is Morgan Brown, who left the academy at Aberdeen, of the Scottish Premiership, in 2019.

Born in Leicester, he attended the camp that year. Brown won the league title in Cyprus with Aris Limassol last season and followed it up with the Cypriot Super Cup in July. The 23-year-old came off the bench in his side’s 2-1 win over top Scottish side Rangers in the Europa League group phase this month.

Martin Onoabhagbe was also part of that 2019 camp. He had been released from Crystal Palace but went on to study sports psychology at St Mary’s University in Twickenham, south west London.

Dylan Thompson came in 2021 after being discarded by Everton. He later earned a full scholarship to play football while studying at the University of North Carolina in the United States.

Daniel Jinadu was at last year’s camp, having been released by EFL club Barnsley. He went on to earn a first-class psychology degree at the University of East London and now hosts the Beyond Football podcast, discussing life beyond the game.

“We are trying to expose them to opportunities that they may not have considered before,” says 44-year-old Rainford, who made more than 400 appearances across a playing career that included spells at EFL clubs Colchester United and Dagenham & Redbridge. “They can hear it from us, but they can also talk about it with their peers and it will sound different compared to an old man like me talking about it.”

“The conversation between them, sharing their experiences, and their peer-to-peer learning is very important,” Morgan says. “It is not just about the football side, but it’s also about the educational side — looking at opportunities, career prospects, and what could be possible next is very important. There is a lot of training, and that could be an opportunity for some of this lot to get back into football.

“The kids here are listening and are eager to learn. They really wanted to take on the advice and probably look for a bit more direction, where they could be going, and what they should be doing. This is what it’s all about.”