Most Memorable Epsom Derbies

is quite a big deal, you might say, but these days it tends to need the prefix Epsom to identify it outside of a circle of hardcore racing fans.

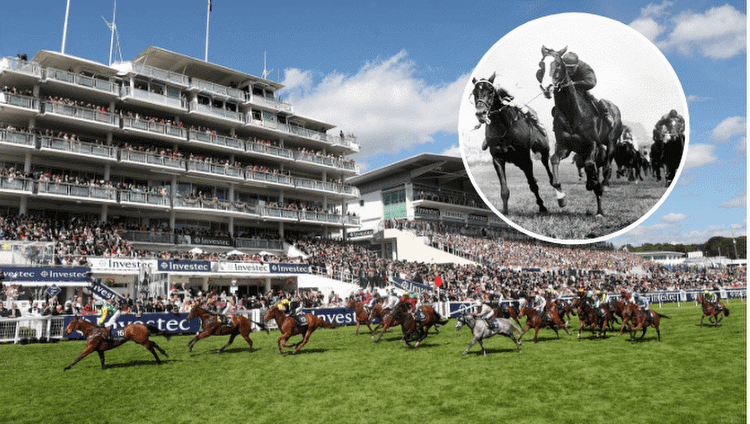

There was a time when the Derby – a key date in the horse racing diary – could mean one thing, and one thing alone, and what happened at Epsom on the first Wednesday in June would see normal life suspended across England.

Long before the Melbourne Cup was invented, and before William Lynn dreamt up the Grand National, the Derby was the original race which stopped a nation.

When something shocking happened on the Downs in early summer, the news was sure to rock the nation, not just wobble the bubble. Here are the most headline-grabbing shocks in Derby history.

Hermit (1867) – A Rivalry Between Two Young Aristocrats

The win of Henry Chaplin’s Hermit in the 1867 Derby had it all. Royalty, rivalry, romance, betrayal, jealousy, scandal, gambling on a grand scale, victory snatched from the jaws of defeat, and the financial ruin and early demise of Henry Weysford Charles Plantagenet Rawdon-Hastings.

The story of Hermit’s Derby is also the story of the rivalry between two rich young aristocrats, Henry Chaplin – a personal friend of the Prince of Wales – and Harry Hastings, the fourth and last Marquess of Hastings. The scandal was the result of Hastings’ sudden elopement with Chaplin’s fiancée, Lady Florence Paget, although his interest in the society beauty faded quickly.

Both men were determined to win the Derby, although while Chaplin was largely concerned with the prestige involved, Hastings was one of the most reckless gamblers of the Victorian era, and was obsessed with the race as a gambling medium as well as a prize in its own right, and set out to back or lay his way to success in the biggest market of all.

When Chaplin bought Hermit as a yearling it is said that the underbidder was Hastings, and the success of the colt as a two-year-old may have fuelled the latter’s jealousy. Hermit became a leading juvenile by winning four of his six races under the care of Newmarket trainer George Bloss and was talked of as a likely Derby winner.

Not everyone agreed, and the fact he only raced at five furlongs and didn’t reappear after winning twice at Stockbridge in June hinted that he might be a horse with problems. Several heavy-hitters were happy to lay him for the Derby, but none so heavily as Hastings, who had no horse of his own for the race, and made his sole focus the prospect of Hermit’s defeat.

Luck seemed firmly on the side of the layer in the run-up to Epsom, as Hermit’s final gallop at Newmarket was a disaster, and confirmed the rumours of his delicate constitution. He pulled up suddenly in his work, blood pouring from both nostrils, and his prospects of winning just over a week later looked gone.

His gallop was held privately, but soon the news had spread far and wide, and his price drifted to 33/1 and bigger. Hastings, who has already laid the horse to lose a vast amount, recklessly opposed him again, when he could have made a small fortune by closing out his bets.

Chaplin and his adviser James Machell had backed Hermit and decided not to scratch him in the hope that their colt would somehow recover. On the day of the race, Chaplin met his rival, and whether through kindness or knowing that the latter would not heed him, he told Hastings that he thought his horse still had a chance of winning and that he could be backed at long odds to offset his liabilities.

Hastings had laid the horse to all and sundry and stood to lose £20,000 (more than £1.25million in modern terms) to Chaplin alone. His words went unheeded, and after the agony of ten false starts, Hastings could only watch in horror as Hermit came late and fast to win the race by a neck, and he left the track a broken man, in almost every sense.

Aboyeur (1913) – A Dramatic Encounter

The fact that Aboyeur’s 100/1 win – which would frighten the life out of modern-day – was the least shocking aspect of the 1913 Derby says plenty about one of the most infamous races ever run at Epsom or anywhere else for that matter. This was the race which was dubbed the Suffragette Derby after Emily Davison met her death by running into the path of Anmer, owned by King George V.

It’s clear that Davison’s actions were meant to raise awareness of her cause, but debate as to whether her death was premeditated act of martyrdom in the name of the Suffragette movement, or a misguided publicity stunt in which her intention was to merely attach the Women's Social and Political Union colours to the King’s horse knowing such an act would make headlines around the world.

The drama didn’t end at Tattenham corner, though, and the finish of the race was possibly the roughest of the century, with much bumping and boring among the leaders in the final furlong, most of it centering around hot favourite Craganour and rank outsider Aboyeur who finished first and second in that order in a bunched finish.

In the confusion, the judge failed to notice the strong late run on the rails of Day Comet, who finished a clear third but was not officially placed.

Most observers believed that the latter was the main culprit, and indeed Aboyeur had a well-earned reputation for being mean-tempered, and true to form, had attempted at least once to savage his main rival as the pair lunged first into and then away from the rails, causing pandemonium among those trying to challenge from behind. The result was expected to stand, so it caused a sensation when the stewards disqualified the favourite.

Rumour had it that the controversial decision was part of a vendetta against C. Bowyer Ismay, brother of the Titanic’s owner J. Bruce Ismay, and therefore considered by many as tainted by the scandal of the ship’s sinking, which had occurred just over a year prior.

To add fuel to that fire, Craganour had seemingly won the 2000 Guineas at Newmarket only for the judge to award the race to Louvois, who raced on the opposite side of the track. It was a bitter blow for Ismay and his trainer, Jack Robinson, to lose the Guineas, but to win the Derby and be thrown out was too much to bear.

Craganour was sold shortly afterward with the proviso that he never run again, and neither owner or trainer recovered from the blow.

Signorinetta (1908) – The Italian Job

While scandal and intrigue have been features of previous Epsom upsets, the story of Signorinetta is one of happy eccentricity and public ridicule turned to joy. Oh, and true love.

Signorinetta was bred, owned and trained by the Italian Cavaliere Edoardo (or Odoardo) Ginistrelli, who arrived in England in 1880 and set up training in Newmarket, where his eccentric ways and odd attire made him nothing more than a figure of fun, although he found success with the filly Signorina, who was unbeaten as a two-year-old in 1889 and finished second in the Oaks the following year as the even-money favourite.

Brilliant racemare though she was, Signorina was a shy breeder and was barren for a decade before producing a colt foal for her owner, a colt by Best Man which he called Signorino, and who was placed in both the 2000 Guineas and the Derby in 1905.

Ginistrelli, an optimist and romantic, then sent his mare to be covered by the champion sire Cyllene, but as she was being led to the covering barn, she refused to pass the box of the stud’s teaser stallion, a horse called Chalereux.

Rather than get annoyed by her truculence, Ginistrelli was captivated, and declared that she was in love. Citing what he called the “boundless laws of sympathy and love”, he abandoned the planned mating and had her covered by Chalereux, whose fee was a paltry nine guineas.

The result of this “love-match” was the filly Signorinetta, and while many in Newmarket had come to grudging respect of Il Cavaliere for his near misses in three Classics, the idea of abandoning reason for romantic notions again made him the subject of amused scorn.

That seemed justified when Signorinetta failed to make the placings on her first five starts as a juvenile, although she eventually won a nursery late in the season.

Unplaced in the 1000 Guineas on her return, and only fifth in the Newmarket Stakes, it appeared that the love match was the disaster that the town’s experts had predicted. Nonetheless, Ginistrelli boxed her up and prepared to send her to Epsom to the amusement of his neighbours, who merely laughed when he addressed them: “Gentlemen, this is the winner of the Derby and Oaks”.

Despite being the only filly in a field of 18 for the 1908 Derby, Signorinetta overcame the odds to win, and win handsomely in the hands of Billy Bullock by an easy two lengths. Tow days later, she won the Oaks by an identical margin at 3/1, again with Bullock doing the steering.

The shock of a 100/1 Derby winner stunned the crowd, but the sight of her delighted septuagenarian owner/trainer/breeder dancing with joy as he came out onto the track to lead her in soon brightened the mood. When King Edward VII invited Cavaliere Ginistrelli to the front of the Royal Box after his filly had won the Oaks, he was afforded one of the warmest receptions ever given to a winning owner at Epsom.

Humorist (1921) – The Bravest of Them All

The abiding themes of Humorist’s 1921 Derby success are bravery and kindness. Humorist was born in the purple and rain in the famous “Black, Scarlet Cap” colours of South African diamond tycoon Jack Barnato Joel. Mr Joel enjoyed great success at his Childwickbury Stud, and was the owner-breeder of seven Classic winners between 1911 and 1914, including 1000 Guineas and Oaks heroine Jest.

Unfortunately, Jest struggled to get in foal, and when she did her first produce failed to survive. When she eventually produced a colt foal in 1918 at the fifth attempt, Jack Joel named him Humorist. He was a handsome if delicate-looking foal, with a pronounced white blaze.

Humorist soon showed his class by winning the Woodcote Stakes at Epsom on his debut, but proved hard to keep entirely healthy, at times going off his feed, and prevented from running at Royal Ascot due to a persistent cough. He was beaten narrowly in the Champagne Stakes and Middle Park, but won his other two races in minor company, going into winter quarters among the market leaders for the following season’s Classics.

Again, Humorist looked brilliant on the gallops in the spring of 1921, but was surprisingly beaten into third in the 2000 Guineas having looked a certainty in running only to falter in the final furlong. Again, he proved a “bad doer” at times, leaving his feed and looking listless some days, but thriving on others.

In the Derby he was at his brilliant best, railing like a greyhound under the inspired but sympathetic riding of Steve Donoghue, and reversing Newmarket form with Craig-An-Eran and Lemonara to win bravely by a neck from the former, with Lemonara an arguably unlucky third having tried to follow the winner through on the rails at Tattenham Corner, only to have the door shut in his face.

In training for Hardwicke Stakes at Royal Ascot, Humorist’s constitution finally gave way to the strain which had been suggested before Epsom, and like Hermit before the 1867 Derby, his final gallop saw him pull up with blood poring from both nostrils. He was immediately sent back home for a prolonged rest. In that period, the great equine artist Alfred Munnings was commissioned to paint the Derby winner.

He took a break for lunch with Humorist’s trainer Charles Morton, telling him that his preliminary sketches needed just another hour before he could go back to his studio to complete the painting, but the artist didn’t get to finish his post-prandial nap before he was awakened by the trainer’s wife who informed him that Humorist was dead.

Stumbling into the Derby winner’s box, Munnings saw a distraught Morton standing over the inert form of Humorist, a huge pool of blood already beginning to seep out of the box and into the stable-yard. The gallant colt had suffered a massive haemorrhage of the lungs.

A post-mortem on Humorist revealed that his death wasn’t merely a fluke, but the result of the advanced tubercular disease which had gone undiagnosed. In retrospect, the colt had been incurably sick since his two-year-old days, and his disease was so advanced when he ran in the Derby that it was suggested he was effectively racing with one lung. Some critics had suggested after his late capitulation in the 2000 Guineas that he lacked courage. In fact, he was undoubtedly the bravest of them all.