Reliving Mazeroski's historic World Series homer perched atop the Cathedral of Learning

Woody Turner couldn’t concentrate.

He was working on an assignment, perhaps for a Roman history class, but he’s not sure. What mattered on Oct. 13, 1960, was that the University of Pittsburgh senior chose to be in — of all places — the library on the fifth floor of a 42-story tower.

From his table inside the Cathedral of Learning, he couldn’t see what was happening a block or so away at Forbes Field.

So, he toggled back and forth to the librarian’s desk, where a radio was playing Game 7 of the World Series between the Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Yankees.

After the second or third inning, with the Pirates ahead, he gave up trying to work. He said to himself, “This is a tall building. There must be a place up on top where I can just get a glimpse of this ballgame.”

About the same time, a Life magazine photographer with a penchant for capturing unlikely angles was coming to the same conclusion.

There were 36,683 people watching live inside the ballpark that straddled the Oakland campus, and millions more were watching from home on black and white TV sets.

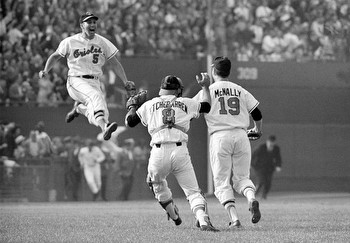

But Turner was one of only about a dozen people who had the view from that outdoor balcony on the Cathedral’s 32nd floor, facing southwest.

It was the ultimate cheap seat with a partially obstructed view of the field. But the position nevertheless immortalized him — or at least the back of his head — in one of the greatest moments in Major League Baseball and Pittsburgh sports history.

Everyone knows about Bill Mazeroski’s miraculous home run. Fewer know what the experience was like from almost 500 feet up.

With a new Pirates season a couple of weeks away, Turner on Thursday ventured back up to the Cathedral’s upper reaches and relived an extraordinary moment from his youth. He graduated from Pitt in 1961, pursued a successful law career and stayed close to his alma mater, heading the alumni association and serving on Pitt’s board of trustees.

A lifelong baseball fan who lives in Oakmont, Turner smiled Thursday at the thought that a bunch of strangers would all get the same idea and, in doing so, create a euphoric image that would be blown up into posters and hung in countless game rooms and dorms.

Back then, Turner was a 20-year-old political science major — too young to be afraid of heights.

It was an impulse decision. He rode the elevator as high as it went, then worked his way lower.

“I started prowling down through the stairs, and then each floor, I tried to see if there was any access point here.”

His persistence paid off on the 32nd floor when he looked out one window and saw the balcony.

“I thought, ‘This isn’t half bad.’ ”

He recalls the window being open and believes at least some already were on the porch, which was formed by a setback in the Cathedral’s Indiana limestone facade.

In the famous photo, he is second from the left in the front row of spectators, wearing a dark sports coat and crew cut, his slender hands raised above his head in jubilation.

“From about the third or fourth inning, what you see in that Life magazine photo, that’s pretty much the way it looked up there. That little porch area was crowded.”

He couldn’t see home plate or much of the third base line, but he did have a good view of center and right field and first and second base.

He also didn’t see George Silk, the Life photographer that day. In fact, Turner didn’t discover there was a photo until 20 years later as he jogged inside a Downtown gym and kept noticing a photo on the wall as he traveled an eight-lap fitness track.

He took a close look and recognized his profile: “I said, ‘Good grief. That’s me.’ ”

“I didn’t know there was a photograph because he came in behind us all,” Turner said. “He did his work. He slipped out. I mean, I never saw him.”

Had he met Silk back then, Turner likely would have wanted to know why in the world the former combat photographer on a sports assignment had wandered up there.

“If Life magazine sends me to Pittsburgh to cover the World Series, it would never occur to me to go up a tall building,” he said. “I’d be down next to the dugout like the other guys, trying to get somebody sliding into home plate or something.”

That afternoon, Nixon and Kennedy were in the homestretch of the 1960 presidential race. Pitt’s Hillman Library did not yet exist. Months earlier, a brand-new eatery that six decades of Pitt students would know as “The O” — The Original Hot Dog Shop — had opened along Forbes Avenue.

With the sun out and the temperature at 70 degrees for the first pitch, those rooting for the underdogs benefited from an oddity that radio announcer Chuck Thompson noted as he came on the air.

The Yankees had scored 46 runs through six games. The Pirates had mustered just 17 runs.

Yet the series was even.

“And should the Yankees lose, of course, people who look back on this series would forever ask themselves, ‘How could the Yankees score all those runs, and still not win?’ ” Thompson said.

Assembled on the field were some of the biggest names in sports. Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Roberto Clemente and Mazeroski, among others. From the 32nd floor, they looked like tiny dots.

Yet, from that perch, they could hear every ball and strike called because of a gadget invented six years earlier: the transistor radio. In the photo, a man behind Turner is holding up the pocket-sized receiver in the foreground.

Though slightly delayed, the audio helped make sense of the sights and sounds below.

“We were getting a lot of help, actually, with what was going on,” he said. “When good things happened, you’d get cheers, and when bad things happened, you get the groans, like when the Yankees would score.”

There were plenty of both as the Pirates, who had jumped out to a 4-0 lead after four innings, fell behind 5-4, then 7-4 by the middle of the eighth inning. The Pirates rallied for five runs to retake the lead after eight innings, only to have the Yankees tie the game at 9, with Mazeroski due to lead off in the last half of the ninth.

On the second pitch of his at bat, Mazeroski tagged what he later told broadcaster Bob Prince was a high fastball.

It was 3:36 p.m.

“I don’t believe I saw the baseball itself leaving the park,” Turner said.

Instead, it was the audio of announcer Chuck Thompson coming through the radio on a slight delay that sparked the reaction 32 stories up: “Here’s a swing and a high fly ball going deep to left. This may do it! Back to the wall goes Berra. It is — over the fence, home run, the Pirates win!”

The celebration seen in the Life photo was just beginning almost 500 feet up. But on the ground, Turner said, “Everybody already knew.”

It was an astonishing end to a game that had been full of twists and turns, like the seeming double-play ball off Bill Virdon’s bat with none out in the bottom of the eighth inning that ricocheted off shortstop Tony Kubek’s throat, injuring him and leaving everyone safe. A five-run rally followed, putting the Pirates up 9-7.

Then, in the top of the ninth, Mantle momentarily froze between bases but slid back into first base, and a Yankee base runner scored. It set the stage for Mazeroski’s walk off.

Game 7 included 19 runs, 24 hits and an error. But it all took place in 2 hours and 36 minutes, according to the box score.

Over the years, Turner has gamely answered questions about that day. Sometimes, baseball fans will bring him a rolled-up poster and ask for his signature, and he obliges.

Building modifications over the years have made the 32nd floor viewing area less accessible. The porch wall is higher.

Turner says the drought that Pirates fans endured in the years before the Maz’s miracle is similar in some ways to what they are experiencing today.

“I’m still looking forward to another 1960 revival here,” he said, smiling at the thought as he looked toward the North Shore. “From here, I can’t even see PNC Park. I’ll have to find a new high place.”

Bill Schackner is a Tribune-Review staff writer. You can contact Bill by email at [email protected] or via Twitter .