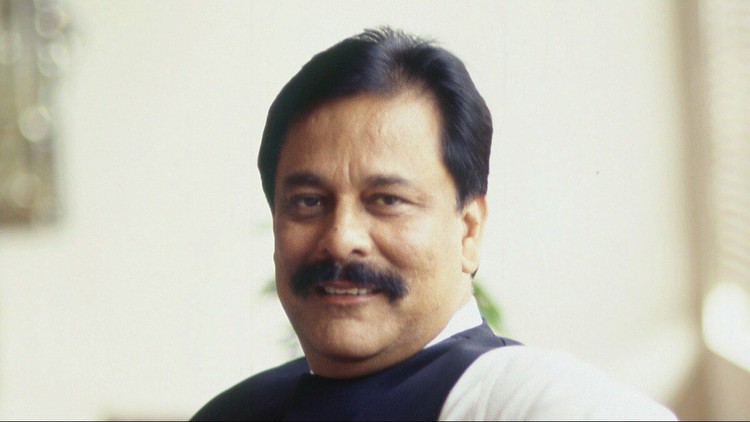

Subrata Roy: When the emperor struck back

Roy’s journey from going door to door selling deposits to homemakers in Gorakhpur to building the Sahara empire

(NOTE: This is a reprint of a story that was published in the INDIA TODAY edition dated January 17, 2011)

Subrata Roy, 62, loves baubles. The shinier the better. His latest is Grosvenor House, the iconic London hotel that overlooks Hyde Park. The managing worker of Sahara India Parivar paid 470 million for it. It’s a glittering addition in a collection that houses a $370-million IPL team, a Rs 558-crore sponsorship of Team India, sponsorships of wrestling, archery, boxing, shooting champions, and a 24,000-acre land bank across India, measuring 15 km by 10 km.

His fingers drip gems advised by his astrologer Krishna Murari Mishra (“Goldie loves him,” he says about the Hollywood actor). His white marble house stands in the middle of a 375-acre estate in Lucknow called Sahara Shahar, with a 2-km long artificial lake, its own petrol station, a state-of-the-art theatre with Gold Class-worthy reclining seats, an auditorium with a capacity of 5,000 people, and airport-type luggage scanners at the exit for everyone who leaves the premises. According to the company, its total group assets have a book value of Rs 54,968 crore and a market value of Rs 1,09,224 crore.

Not bad for a man who would go door-to-door selling deposits to homemakers in Gorakhpur on a scooter his father had given him. “I started Sahara with deposit mobilisation in 1977. I had a peon and a clerk. It was a Rs-15 scheme and I sold 10 forms a day.” The son of a sugarcane technologist who worked as a chief engineer for the Thapars, Roy takes pride in his nine-crore strong Sahara “family”. That spirit of community probably has something to do with his days as an NCC cadet. He led a Republic Day contingent in 1967, was attached to the army for 40 days, and then was cadet adjutant for all annual camps. “I learnt from two things in my life—my father and the NCC.”

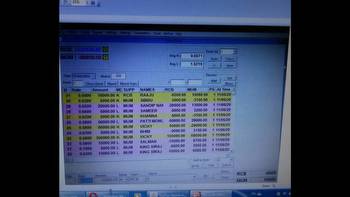

He’s had his troubles, not least of them being a whiff of suspicion over the pace at which his fortunes have risen, through a business as fragile as loan deposits. In 2008, the Reserve Bank of India asked Sahara India to repay its deposits as and when they mature and bring down the aggregate liability to zero on or before June 30, 2015. This could have been devastating but Roy negotiated his way out. Roy brushes the issue aside, saying he’s ahead of the deadline. But the Securities and Exchange Board of India has raised questions about the money Sahara has got from retail investors through housing bonds. Roy is currently contesting that and on January 4, the Supreme Court refused to stay two Sahara Group firms from raising funds.

He certainly has gall. When he got his obligatory minute with US President Barack Obama at the formal dinner at Rashtrapati Bhavan in Delhi, he carried a framed picture of himself. Roy has now shifted his focus overseas. He’s identified an enormous space near Oxford Street to house his new pet project, an Indian luxury artisan label, Mastercraft. In typically self-congratulatory fashion, he says it will have a club which “will be the best in Europe”.

He’s looking at oil exploration in Jordan, Georgia and Australia as well as iron ore and bauxite mines in South Africa because “my friend Ajay Gupta is calling me” (Gupta is the influential head of the South Africa-based Sahara Group). There’s also a proposed commodities cell in 16 countries and an overhaul of the 420-room Grosvenor House. “After the global meltdown, a lot of assets are for sale globally,” he says. His plans for real estate at home remain on track—214 middle class townships with 2,600 houses, in addition to the existing 10,600 acre Aamby Valley City.

He has also put behind him stories of a mysterious illness in 2004. He can laugh about it now but he recalls hearing some weird rumours: “People suggested that I was being locked up by my wife and younger brother. What nonsense.” He says he was battling wildly fluctuating blood pressure and a social schedule that was forcing his own staff to wait for days to catch his attention. “I realised I had to change my lifestyle. I decided not to travel, to sleep eight hours a day, do yoga and play badminton.”

He’s now back to working 20 hours, 30 days a month. When he’s not presiding over the mini Disneyland called Sahara Shahar, its greens dotted with a tiny medieval castle, two raised ponies about to cross a steeplechase, a gigantic statue of Bharat Mata, a replica of a Hooghly boat, and smaller statues of freedom fighters, he’s running off to London.

The work hard-party harder days are back. “My father told me that he would never leave anything behind for me when he died because if you materially secure a guy he becomes useless. He gave me the freedom to do masti while he was alive. Every year, I would fill up some form and pretend to go to a city to take an exam or join a coaching class.” After his father’s death, times were a bit tough and his wife, Sapna, a gold medallist from Hyderabad’s Osmania University, even pawned her jewellery. “That made me so insecure that on every birthday and anniversary, I would buy her so much gold that she told me to stop at one point of time. It was getting too much,” he says.

His studies were erratic and itinerant. He studied in Bettiah; in Dharia, both in Bihar; in Benaras; then went to Chandigarh to do a year of B.Sc in DAV College and finally did a three-year diploma in mechanical engineering from Gorakhpur, coincidentally from the same institute as his father. He was obsessed with joining the air force, but was prevented from doing so by his mother, Chhabi, the reigning matriarch of the family. When he couldn’t, he decided to start a business. He’s done all sorts of things. Loaded sacks on a truck for two days, devised a test for silver purity which he sold for Rs 4 a unit, won a contract for underground trenching and supplied stainless steel to a fertiliser factory.

Along the way, he’s collected interesting friends. He loves to let their names drop, thinking nothing of interrupting the interview to conduct a loud, long-distance discussion with “Shah Rukh bhai” on the phone. He mentions Mother Teresa (“whenever she held my hand, a current would pass through me”) and produces a picture of them together. “She was a jovial lady,” he says. He says it is an “honour and privilege to have ever helped” Amitabh Bachchan. “But I did it for myself. He’s such a personality that you can do anything for him.” Sometimes his friends cause him vexation, like Amar Singh. “I told him once, you are free to have your friends. But if you have a tiff with someone, don’t expect me not to be his friend,” he says. Roy had dinner with Amar Singh and Sanjay Dutt just a few days ago. “And in London, two months ago with Boney and Sri (that’s producer Boney Kapoor and his wife, actor Sridevi). Then we went to the A.R. Rahman concert,” he says.

He says he has good relations with politicians across party lines. “I am in business in Lucknow. Any chief minister should be a friend of mine. Rajnath Singh was such a great friend of mine. I would meet Kalyan Singh when he was cm every alternate day.” Except Mayawati. “I think she doesn’t like me because of Amar Singh and Mulayam Singh.” He thinks he willy nilly became identified with the Samajwadi Party because he asked Amar Singh to stay with him at Sahara Shahar for a year-and-a-half “when there was a threat to his life”. Also, because he hosted all Uttar Pradesh State Industrial Development Corporation (UPSIDC) meetings in Lucknow.

He speaks of his big buys with the same passion that he devotes to describing how he got artisans from Firozabad to recreate a Rs 66-lakh Belgian chandelier in his office for Rs 6.5 lakh. Or personally selecting models who were carrying country flags in the opening ceremony of the Commonwealth Games. Or locating 85 people he went to school and college with and giving them jobs in his empire.

For his new hotel acquisition, he plans a spa, a nightclub, “at least five to six more restaurants including one grand Indian restaurant”, maybe a casino and roundtable dinners with the finest shows in its vast banquet halls. “1 Park Lane will be the best spot in London for the weekend,” he says with enthusiasm. Grosvenor House, indeed London, may never be the same again.