U.S. took long, strange trip to rugby gold in 1924, last time sport was in Olympics

RIO DE JANEIRO -- Within a span of several days, members of the 2016 U.S. Olympic rugby team flew from Florida to their training center outside San Diego, then quickly flew on to Houston. They spent the night there before taking a red-eye down to Rio, where they arrived last week.

A long journey, right? Yeah, well, it was considerably easier than the 1924 U.S. rugby team's odyssey to the Olympics in Paris 92 years ago.

For one thing, the 1924 team had to raise its own funds for transportation to Europe and lodging in Paris because the U.S. Olympic Committee wouldn't pay. Then the team had to take a six-day, cross-country train ride from California to New York, which was followed by a nine-day cruise across the Atlantic Ocean. Once there, the players received so much hostility that they had to battle their way off the ship when it docked in France. They were jeered during and after their games and also had their money and possessions stolen from the locker room.

And yet, they won the gold medal, defending the Olympic title they had won in 1920.

Yes, the United States won Olympic golds in a sport that was barely played in America then -- or now -- which makes the Americans the defending gold medalists as rugby returns to the Olympics for the first time since the 1924 Miracle at Paris.

"America's victory in rugby football at the VIII Olympiad represents what is probably the most surprising of all victories, secured in the face of severe handicaps and almost unsurmountable obstacles," 1924 U.S. rugby team manager Sam Goodman wrote afterward in a report to the U.S. Olympic Committee. "This year's victory is another object lesson to the world of the American youth's athletic adaptability."

And 92 years later, the 2016 U.S. team can draw inspiration from its forebears.

"It was guys coming together and given no chance at all," said 2016 U.S. rugby player Madison Hughes. "They toured England before the Olympics. They were told, 'The French are going to kill you.' But they came out against all odds, because rugby wasn't a huge sport in the U.S. There were a lot of guys who hadn't played a lot of rugby -- some hadn't played it at all -- and some playing other sports in the Olympics.

"It was just guys coming together and representing their country with pride and doing everything they could to bring home gold."

Like now, rugby was not played by many people in the U.S. in the 1920s. The sport had grown somewhat in popularity earlier in the century, when deaths and injuries caused considerable concern over American football. But when football came roaring back, colleges dropped rugby during the 1910s. The U.S. sent a team in 1920 only because the California Rugby Union pushed hard for it.

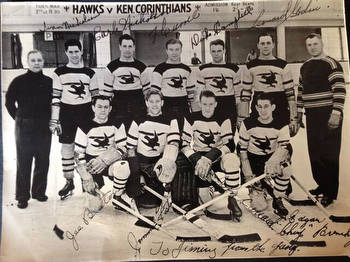

California was the place where rugby had peaked in popularity, and almost every player on the 1920 and 1924 U.S. Olympic teams lived there. Even so, there were a few team members who had never even played the game until a few months before the Games started.

Regardless of whether they had rugby experience, the U.S. players could boast of great athleticism. In addition to playing rugby on the 1920 team, Dink Templeton finished fourth in the long jump. Teammate Morris Kirksey also competed in the 100-meter race, finishing second to Charley Paddock. Kirksey's speed was an asset that made up for his lack of rugby knowledge.

Among the most prominent American rugby players of the era was Colby "Babe" Slater, who played rugby in high school, was a multisport star at UC Davis, was on the 1920 U.S. team and captain of the 1924 squad (his brother Norman was on the 1924 team as well). Slater also served in World War I in the medical corps, risking death while experiencing some of the most horrific sights imaginable in Belgium --- then returning there for the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp.

Another top U.S. player was Rudy Scholz, who also played on both gold medal teams. He loved rugby so much that he would continue playing it all the way into his 80s. He and Babe Slater are the focus of Mark Ryan's excellent book on those teams, "For the Glory," where Hughes learned much about what the teams endured.

While the U.S. did not have a lot of rugby experience, at least it didn't face a lot of opposition. Because of disagreements over requirements, scheduling and expenses, just two countries competed in 1920.

The Americans' opponent in the one-game event was France, the overwhelming favorite. But playing in wet and sloppy conditions, the U.S. upset the French 8-0 to win gold. And set up the incredible 1924 adventure.

Out of a desire to gain revenge, the French Olympic committee sent a request to the California Rugby Union that it compete in the 1924 Games.

As U.S. player Norman Cleaveland told Mark Jenkins for a 1989 story in American Heritage magazine: "They were looking for a punching bag. We were told to go to Paris and take our beatings like gentlemen."

It was even more unclear whether the U.S. would compete in 1924 than it had been in 1920. An additional four years had passed since colleges had dropped rugby, leaving even fewer experienced players available.

"This invitation was considered from all angles," U.S. coach Charlie Austin wrote in his report to the USOC. "As rugby was a dead issue with us, as we had ceased to play it as a popular sport in 1914, we did not know whether we could gather a team which would do credit to the United States."

Eventually, the California club and the USOC chose to accept the invitation, though, as Goodman wrote, it had to overcome many obstacles such as "lack of organization, equipment, finances, players, and the necessary facilities."

Although the Olympics were to open in July, the rugby games were held in May. The U.S. team took a train across the country and sailed to England aboard a ship in April. After arriving in England, it played three helpful games against very welcoming British teams before heading across the Channel to France.

That's where the obstacles got worse. When the ship docked, French officials were not willing to let the Americans disembark because of issues with their visas.

"The trip next morning from Folkstone, England, to Boulogne, France, was extremely rough and we were in no mood for the unpleasant reception we received at the hands of the officials of the country who was supposedly entertaining the world's athletes," Goodman wrote. "There was no one to meet us; our baggage was seized and for a time we were not even allowed to land on French soil, simply because the French Olympic Committee had not taken care of our visas."

There were reports that the U.S. rugby team formed a scrum to force its way off the ship and past French security. Cleaveland told Olympic historian John Lucas, a Penn State professor, for a paper in 1986: "We started a near riot, crashed the fence and made our way to Paris through hellish rain."

Bob Latham, the current chairman of U.S. rugby, has heard many tales about the docking. "They were absolutely being turned back," he said. "Even when they hit land, they were outrunning the authorities."

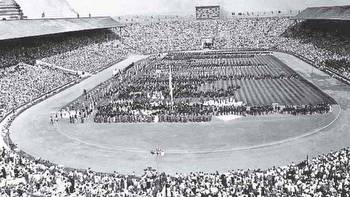

All of which led some in the French newspapers to refer to the U.S. players as "streetfighters and saloon brawlers." Goodman also wrote that the U.S. team was forced to train on a "miserable field" near their hotel until they were finally allowed into Colombes Stadium, where the Olympics were to be held. According to Ryan, some in the French media even denied that the U.S. had won the 1920 gold medal in rugby.

"Without going into details about our stay in the French capital," Goodman wrote, "it is only necessary to remark that we were accorded anything but hospitable treatment; in fact, many times we were treated with open hostility."

Why such hostility at an Olympics, especially after the U.S. had played a decisive role in beating the Germans and Austrians in World War I when it joined France and the Allies in 1917? For one thing, Ryan writes, the French were upset by U.S. president Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points after the war, which included softer punishment for the Germans.

Plus, the French rugby fans wanted to get the gold medal back.

There was slightly more rugby competition in 1924 than 1920: Romania joined to make it a three-nation contest.

The U.S. again wasn't considered much of a threat, but at least America was better than Romania. In perhaps the worst Olympic performance that ever "earned" a bronze medal, Romania went 0-2, losing 61-3 to France and 37-0 to the U.S. That set up a rematch of the 1920 gold-medal game.

Although it lacked some rugby experience, the U.S. team made up for it with its size and tackling ability when the game was more physical.

"From contemporary reports, it was the physicality of the Americans," Latham said. "We may not have had much rugby skills, but we knew how to tackle. That these guys were able to lay things on the line and play a very physical game is what carried them through it all."

The U.S. was jeered in the championship match against the heavily favored home team. Nonetheless, the Americans' tackling approach helped them take a 3-0 halftime lead and knock star French player Adolphe Jaureguy out of the game, along with another player. Those injuries helped the U.S. dominate the second half and beat France 17-3.

The French fans were not happy. They booed the Americans so heavily (with some fans throwing bottles) that the team had to be escorted out of the stadium by police, and a few U.S. fans were even assaulted in the stands and had to be hospitalized.

"Thank goodness for the 9-foot-high fence between us and the slaughter-minded fans," Cleaveland told Lucas.

Men like Babe Slater and Scholz were disgusted by what they saw, Ryan writes in his book: "Like so many others, they had been willing to risk their lives in the First World War to restore France's freedom. ... Such a display of hatred from a supposed ally was beyond their understanding."

As unpleasant as that match was, conditions improved afterward when the U.S. team traveled through France playing exhibitions. "They won over the players and the French rugby people," Latham said. "They extended their tour and were actually respected."

They should also be remembered.

"Our victory in 1924 made the hockey win against the Soviets look like an everyday occurrence," U.S. player Charlie Doe told Jenkins. "If we had that kind of coverage, rugby might be the great American pastime today."

Rugby was dropped from the Olympics after 1924 and would not return until more than nine decades had passed and all the gold medalists had died.

In large part, this was due to the departure of Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics. He loved rugby and was a force behind its place in the Games. He left as IOC president following the 1924 Games, and his replacement, Count Henri de Baillet-Latour, did not favor team sports in the Olympics. Thus, rugby did not survive.

"Coubertin certainly championed getting rugby into the Olympics. ... So losing him as a champion of it, I think, certainly hurt," Latham said. "Not only how he exerted influence in Olympic circles, but how much he wanted to exert after France lost gold-medal matches in 1920 and 1924."

Few people today know about the 1920 and 1924 U.S. teams, though UC Davis has presented an award named after Babe Slater to the school's top male athlete since 1965. The university also is making sure to highlight his achievements this summer -- not that Slater pumped his accomplishments much.

"He never overly talked about it," said Dick McCapes, his son-in-law. "I was aware that there were Olympic diplomas and medals in his office, but I never fully appreciated his accomplishments until much later in life. If you asked, he would talk about it but would answer briefly. He was focused on the present."

Slater would be focused on the Rio Games, because rugby is finally back, albeit in the rugby sevens form. There will be a dozen teams competing, including New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Fiji and Great Britain but not Romania, which will make winning gold again considerably more difficult.

"The players now are much better, and there are more opponents to play," Latham said. "The competition is stronger, more athletes are coming to the sport as the sport of first choice. More people are in their prime physical years. They have rugby instinct. Just the opportunity to play and the coaching has become much more organized and sophisticated. And more mainstream."

While the competition will be tougher, the U.S. players are better. So they could win gold, just as the 1924 team did. And at least they didn't have to pay their own way to Rio or fight their way off the plane when they got here.

"The first thing [this team] should take from 1924 is that's our gold medal to defend," Latham said. "We don't want to lose that."