'We have every right to be cautious': How Propositions 26 and 27 could transform tribal gaming

A pair of dueling propositions that could seriously expand sports betting across the state comes with high stakes for Native American tribes whose economic prosperity and gaming operations are closely tied, including many in San Diego County.

Proposition 26 would allow in-person sports betting at tribal casinos and horse racetracks; Proposition 27 would allow online sports betting on platforms run by tribes as well as gaming companies such as DraftKings and FanDuel, which are funding it. If both measures pass, only the one with the most votes would take effect.

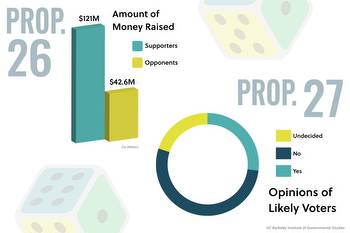

A record amount of money — more than $550 million — has been funneled into the two measures. Local tribes, including those in Temecula, have donated nearly $100 million to support Proposition 26 and oppose Proposition 27, according to state campaign finance records.

The competing measures stand either to buttress or to destabilize one of the most important economic engines for reservations across the state. For tribes, which have limited options to finance their operations, revenue from tribal casinos pays for many essential services on reservations, including police, fire departments, medical care, housing, infrastructure and educational programming, like the Kumeyaay Community College.

“All of those things are made possible from Indian gaming,” said Chairman Cody Martinez of the Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation.

Under Proposition 26, that revenue could significantly rise. But if Proposition 27 passes, some tribal leaders worry that legal online sports betting could threaten the viability of their own gaming operations, and the key funding they provide.

As Election Day nears, San Diego County voters appear unconvinced on Proposition 26 and broadly opposed to Proposition 27.

According to a poll released last week by SurveyUSA for The San Diego Union-Tribune and KGTV 10News, 58 percent of local voters oppose Proposition 27, while 27 percent support it. Voters were more closely split on Proposition 26, only slightly more opposed than supportive — within the poll’s margin of error. Support was highest among the small percentage of voters who regularly visit tribal casinos or bet on sports.

Already, the intense campaigning has made the two propositions the most expensive since the 1999-2000 election cycle — the earliest the state provides data for — with spending on Proposition 27 alone far surpassing the more than $220 million record spent on Proposition 22 two years ago.

Both propositions have garnered more than $100 million in contributions, but most — more than $380 million — has gone toward Proposition 27. The measure stands to significantly change the state’s gambling landscape.

Leaders of four of California’s most successful Native American tribes with gaming interests are the original proponents of Proposition 26. The measure would legalize sports betting — but only in person at tribal casinos and the state’s four privately owned racetracks. It would also legalize roulette and dice games like craps.

A coalition of more than 30 tribes support Proposition 26, with major funding from the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians in Palm Springs, the Barona Band of Mission Indians in Lakeside and the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation in rural Yolo County.

In San Diego County, its supporters include the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians, La Posta Band of Mission Indians, Los Coyotes Band of Cahuilla and Cupeño Indians, Pala Band of Mission Indians, San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians, Sycuan and Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians.

Proposition 27 would go further, allowing sports betting from computers and smart devices when they’re within state lines.

Under Proposition 27, gaming companies — such as DraftKings and FanDuel, which control a large swath of the U.S. online sports betting market — would have to partner with a California tribe and pony up $100 million to get licensed in the state. Tribes could also offer sports betting platforms on their own for a $10 million entry fee.

Tribes and gambling companies with sports betting licenses would pay 10 percent of their take from sports bets each month to the state, after subtracting some expenses and losses. Most of that tax revenue would fund programs for homelessness, mental illness and gambling addiction, with a smaller cut for tribes that are not involved in online sports betting — money its supporters have pointed to and argued is key to fighting homelessness.

Opponents, including 10 San Diego tribes, worry Proposition 27 would drive business away from tribal casinos and let existing sports betting platforms control the market in the state.

That is Martinez’s concern.

Sycuan was one of the first tribes to offer gaming in the region when it opened its high-stakes bingo hall in 1983, he said. Over the years, gaming there has grown, and now the Sycuan Casino Resort boasts more than 50 tables, 2,400 gaming machines, a number of restaurants and a $260 million hotel resort.

Martinez, who opposes Proposition 27, believes legalizing online and mobile sports betting will hurt tribal finances across the state.

“The tribes have every right to be cautious of changes or growth of gaming in the state,” he said. “We fought for it with blood, sweat and tears, as I like to reference, and we have every right to be cautious and protective over the industry that we’ve built.”

Tribal gaming in California has grown into a nearly $20 billion industry, the American Gaming Association reports, since a 1987 Supreme Court decision involving two California tribes — the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians and the Morongo Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians, both in Riverside County — opened the way for a major expansion. In that case, the court ruled that neither the state nor the county could regulate card game and bingo operations on tribal lands.

In 1998, Californians voted in favor of authorizing tribal casinos through Proposition 5, which was later deemed unconstitutional by the court. Following that decision, voters passed Proposition 1A in the March 2000 election, amending the state Constitution and allowing the governor to negotiate compacts with federally recognized tribes to operate certain types of gambling on their lands.

Wide legalization of casinos has had a major impact on tribes across the country.

Tribally owned businesses are generally the primary funding source for tribal governments, whose lands are held in trust under the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Because of the trust status of reservations, tribal governments are unable to levy and collect property taxes, and many also don’t impose income taxes on their citizens, according to the National Congress of American Indians.

In a 2018 paper on tribal sovereign nations and planning, the San Diego Association of Governments reported that gaming and other development on tribal lands in the county has led to rapid growth for a number of tribes, created more than 10,000 local jobs and resulted in a $1 billion industry.

A 2019 study from the University of Washington School of Public Health found that tribal casinos are correlated with significant health improvements among Native Americans within Native communities in California. The study found that the tribes with casinos — about half of the 81 tribes surveyed — had more resources for health, community and recreational infrastructure.

“Colonization has done a number on California tribes, as is evident by our small population size and our land base size,” said Joely Proudfit, a California State University San Marcos professor who is involved with the No on Prop 27 campaign and has worked to support tribal gaming in California since the Proposition 5 campaign in the late 1990s. “Tribal government gaming has really been the one economic development opportunity that has worked for tribes.”

In addition to California tribes themselves benefitting from building casinos, each non-gaming tribe in the state — primarily those in rural areas unsuited to gaming — also gets $1.1 million in funding each year through the Revenue Sharing Trust Fund, according to a state Legislative Analyst’s Office report.

A spokeswoman with the No on Prop 27 campaign said the tribes she has spoken with are primarily focused on Proposition 27 failing during the upcoming election.

Proudfit, however, thinks there may be a battle in the courts should it pass. “If Proposition 27 were to pass, I think the tribal nations would use every legal remedy they could find,” she said.