Famous rugby players' very different jobs emerge before they made it

We all know the famous rugby players of yesteryear combined playing duties with careers outside the sport throughout the amateur age, but plenty more recent and current players had to grind for a living as they hoped their skills on the pitch could turn into something special.

Here, we take a look at their stories.

Finn Russell (stonemason)

He's now thought to be the best-paid rugby player in the world with his wages at Bath reportedly approaching £1m a year, but many years ago, Finn Russell lived a more humble existence

Russell worked for three years as a stonemason after secondary school, getting paid £300 a week while also pocketing £50 for playing amateur rugby with Falkirk RFC. Speaking to The Scottish Sun, Russell said: “On rainy days it could be pretty miserable… It could be tough but I enjoyed it.

“I’d be making windowsills, door frames, fire places – even building walls. But compared to playing rugby, it’s night and day. If I ever have a bad day at training, I think back to what it was like working in that cold shed.”

Liam Williams (scaffolder)

During his time at Waunarlwydd, Williams worked as a scaffolder at Port Talbot steelworks, rigging scaffolding above a blast furnace at heights of up to 250 feet.

It wasn't work for the faint-hearted, but then Williams has always been anything but that.

"He was always going to be a rugby player as he was so good at it, at a young age. He was brilliant," added Brian. "At a young age nobody could ever catch him.

"One game he played as hooker and he went out through the No.8s legs and he was gone."

Williams the full-back had previously spoken of his previous life working at the steelworks, saying: "The highest I climbed was about 250 feet and you are just looking down at the floor. I worked on the top of the blast furnace and that may be even higher. It was fine and it's not something that bothers me."

Fear has rarely weighed him down.

Lee Byrne (apprentice carpenter and joiner, cable cutter and forklift operator)

The former Wales and Lions full-back flirted with the idea of joining the army.

In fitness testing, candidates had to do a one-and-a-half-mile run in under 10 minutes and thirty seconds.

Byrne did it in six minutes and 30 seconds.

The military sorts took him aside and asked if he wanted to join the Paras. He was tempted but instead opted to return home, taking a job stuffing cushions in a furniture company.

His dad then found him an apprenticeship as a carpenter and joiner.

For 18 months he worked in London, doing up the Plaza Hotel, and travelling over the continent to places like Prague, Munich, Paris and Rome. Of his experiences in London, he says in his book The Byrne Identity: “I loved it. All of a sudden I was earning £300-£400 a week, a king’s ransom for a teenager. I was enjoying getting my hands dirty, and the camaraderie of my workmates. The social life was amazing.”

Other posts saw him work as a learning disability support provider and he also cut cable and drove a forklift truck for Morelec, eventually moving on to a similar role for Edmunson Electrical, where came under the influence of a colleague, former Bridgend RFC scrum-half Brendan Roach, aka the fittest man in Bridgend.

Roach trained assiduously and watched his diet. Byrne worked with him and progressed rapidly. A couple of breaks later, via Bridgend Athletic and Tondu, and the Scarlets became interested.

Byrne never looked back.

Joe Launchbury

The England international was actually released by Harlequins at the age of 18 and ended up getting a job in the local Sainsbury’s to ensure he could continue his rugby career with National 2 North side Worthing.

He took on a role in the bakery section and says it was a "good grounding" for him and made him appreciate what hard work is.

Adam Jones (patio-slab maker)

He became one of Wales’ greatest tighthead props, but there was a time when he wasn’t thinking of becoming a professional sportsman.

His weight had ballooned to 23 stone and he had secured a position making patio slabs.

Then Neath RFC came in for him after inviting local boys to train with them following the establishment by the WRU of an U21 league.

"I never came through the academy structure," Jones told the BBC. "I love rugby, but there are bigger things in life.

"Even when I turned professional with Neath, there was an amateur culture. I can't imagine many of the boys these days having ever had a job. Making slabs was hard work, starting at half seven every day."

He joined a rugby course set up by Sean Holley in Llanelli.

Jones also had a summer job dressing up as a bear in Dan-yr-Ogof Showcaves.

Playing for Neath U21s against their Cardiff counterparts, Jones was part of a dominant scrum that paved the way for victory. Exiting the field he came across what he calls in his book Bomb, My Autobiography “the near-mythical figure of Lyn Jones, Neath’s first-team coach.

“He approached me quite earnestly and said: ‘You played well out there, young man’, before slapping me hard in the guts and saying, ‘now go away and get rid of this, will you?’

Jones was on his way.

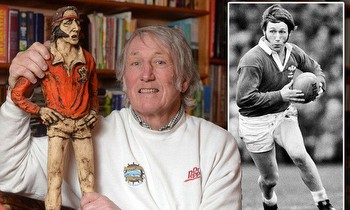

Shane Williams (job centre worker)

Initially made and fitted windows “working my socks off” for around £30 a week. “I was treated like dirt and regarded by everyone as the company’s dogsbody,” he says in his book, Shane, My Story.

After wading through several other jobs, he landed a post at a job centre, dealing with the unemployed and helping them to find work. He proved good at it and was promoted. “I loved it,” he says in his book. “I liked the fact that every day was different.”

But it wasn’t long before Neath came calling and soon after he broke into the Wales set-up.

Brilliance couldn’t be held down.

Gareth Thomas (postman)

In his early days for Bridgend, Thomas earned £25 a week through rugby.

He used it to top up his wages as a postman.

His dad had helped secure him the post.

Thomas junior says in his first book, Alfie!: “My dad and I used to get up at 4.30am to go to work. We would drive in together when we eventually got a car, but before that we would have to get up at 4am and hope we could flag down one of the lads on their way to stop and give us a life.”

He gave up the role after Bridgend offered him a post as a development officer.

“I was sad to leave,” he says in Alfie.

“OK, the pay wasn’t a king’s ransom, but as long as I had £50 in my bank account on a Sunday night to see me through the week for petrol and food, I didn’t care. They were great days, and I often think now what it would be like to go back to those times.

“Working on the post, playing for Bridgend, out with the boys every Saturday night — what a life!”

Allan Bateman (pathology lab worker)

Those who followed Maesteg RFC in the 1980 knew there was a hugely promising young centre by the name of Allan Bateman coming through.

He had electric speed over 20 metres, could step and tackle with venom.

He could do all that despite working 80-hour weeks in the pathology lab at Morriston Hospital in Swansea.

The long hours continued after his switch to Neath. A move to rugby league, with Warrington, followed in 1990. "Part of the reason I quit Neath and joined Warrington in 1990 was because the hours I was putting into my job and my rugby were becoming too great," Bateman later said.

"I was working a full day in the pathology laboratory in Morriston Hospital, training with Neath and then training with Wales. It was ridiculous.

"What I really needed was for someone to come along and offer me some help so that I didn't need to work so many hours. A sponsored car would have eased the burden, or something that allowed me to work part-time. That didn't happen, I got a bit disillusioned and out of the blue the rugby league offer came along. I admit I didn't really think it through totally, but I decided to go."

Mark Ring (civil servant)

The gifted fly-half or centre started working as a civil servant at Companies House in Cardiff in 1980, having come through the interview.

“I got the job and was put to work in the post room, where I was basically opening letters all day and was bored senseless,” he says in his entertaining book, Ring Master.

There was a disciplinary scrape Ring negotiated. “The one good thing to come out of it was that my bosses realised I was a young man making my way in the sporting world and needed to be doing something that I was going to find more of a challenge. Their answer was to place me in the mortgage department — unfortunately, I found that only slightly more interesting.”

Throughout his time there, employees had to work seven hours and 24 minutes a day, figures that were still ingrained in Ringo’s mind when he penned his book a quarter-of-a-century or so later.

Want the latest Welsh rugby news sent straight to you? Look no further.