Mantovani’s grand plan, the Seven Dwarfs and Vialli’s vow

This is part of a series of articles inspired by questions from our readers. So thank you to Tom E, who asked us to look at the forgotten triumph that was Sampdoria claiming the Serie A title in 1991.

What is it about Samp?

My wife is not a football fan, but if Samp ever crop up in the unpredictable shuffle of the quotidian, she will express the sort of appreciation that always catches me a little off guard.

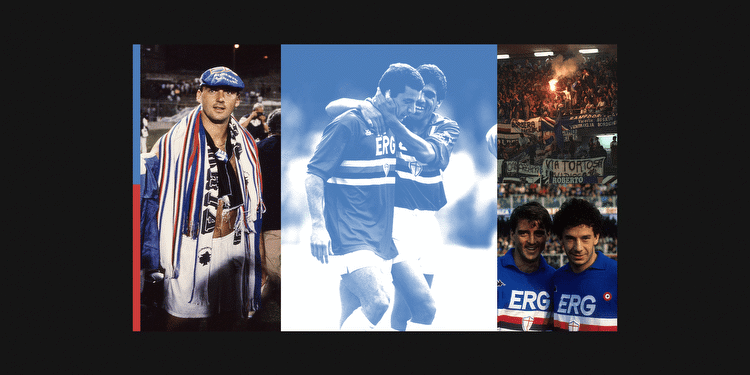

I once showed her a sepia-toned photo of the 1991 team dressed up as footballers from the early 20th century. Luca Vialli organised the shoot to raise money for the Gaslini childrens’ hospital. The shorts are ludicrously long and the peacocking poses absurd.

Toninho Cerezo has his head bandaged up like a plunger. Vialli is down on one knee with a pair of round spectacles resting on his nose. There’s an executive in a waistcoat, tie and boater hat like an Oxbridge grad and the adorably avuncular coach, Vujadin Boskov, is stood to the side, scarf round his neck with the cutest and best-behaved pug in all of Genoa — “what a good boy” — on a leash.

As a club, Samp are unfailingly simpatico. Some might coin the neologism ‘Sampatico’. Unless you’re Genoano with a bit of Griffin in your blood or a Roma fan who has never been able to get over 2010, when a Giampaolo Pazzini brace extinguished your team’s title hopes, it’s damn hard not to like Samp.

Whatever the Genoani say about them looking like a gruppetto of cyclists, the blucerchiato jersey remains probably the best original design in football.

As a Brit, it’s odd that Genoa, the oldest club in Italy and one of its most successful, founded by the Englishman Sir James Richardson Spensley no less, does not, at least on this sceptred isle, inspire the same affection as their cousins.

And yet, at the same time, it makes perfect sense when the Panini sticker album of the mind flicks through the pages of Samp seasons past, featuring Graeme Souness, Trevor Francis, David Platt, Des Walker, Lee Sharpe (!) and DANNY DICHIO, not to mention the indelible mark Roberto Mancini and Vialli later left on the Premier League. It has helped Samp transcend.

After all, a fan of Samp isn’t necessarily someone stood barefoot on the sands of Bogliasco, the surf washing over their toes, a pipe lodged firmly in cheek like the Baciccia (the Sampdoriano Mariner) silhouetted on the club’s badge.

A fan of Samp, much like a sailor, could be anywhere — a sentiment captured beautifully in the club’s anthem, Letter from Amsterdam: a love letter sent from afar musing on what the girl in his life, la Samp, is getting up to on a Sunday afternoon back in Genoa.

The Scalzi brothers wrote that song in the year of Samp’s Scudetto, taking inspiration from a photo in the office of the club’s owner, Paolo Mantovani. It was taken in Copenhagen rather than Amsterdam and showed the Little Mermaid statue with a Samp scarf around her neck. Near, far, at one time in our lives, Samp have touched many a football fan’s heart. Stolen them even.

“Samp’s like a beautiful girl that everyone wants to kiss,” was Boskov’s way of putting it. They played with heart, the same heart of “a mother who loves her children” and la mamma, la madonna, is sacred in Italy.

Deep down, this has always been a story about family. That’s the legacy of the 1991 team. Samp represented football as it should be, a football that’s maybe gone forever.

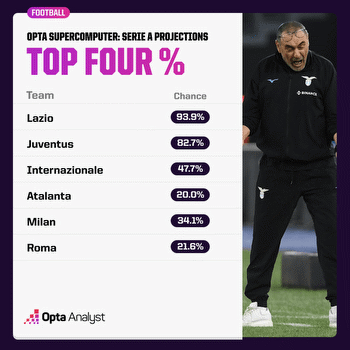

Napoli winning the league this season, as they surely will considering their 19-point lead, has its romance and genuine social significance for Neapolitans and the south of Italy. The pride and redemption. Champions AD (After Diego). But it has come at a cost. No one outside Juventus has paid more for a player than Napoli did for Victor Osimhen (€75million; £65.9m; $80.7m).

Samp 1990-91 were different. How they set up, the make-up of the team and the way they won pretty much ticks every box of what any fan would want from a football club.

As an entity not too much older than Paris Saint-Germain — Samp were fused together only in 1946 — they cannot be considered arriviste. Mantovani’s money came from oil but he could not compete with the Agnellis and the Berlusconis of this world. His grand plan was to go Italian. Mantovani sent his sporting director Paolo Borea out to find the best young players in the country and promised them the time and patience to fulfil their potential.

Luca Pellegrini, the captain, was 17 when he joined from Varese. Mancini wasn’t much older upon leaving relegated Bologna as Samp gained promotion. Gianluca Pagliuca, the Aston Villa-supporting goalkeeper, was barely 20 when Borea raided Bologna again. Vialli was that age, too, and came from Cremonese, as did the lambada-dancing Attilio Lombardo. Marco Lanna, their current president, rose through the academy.

The team grew up together. Samp was their adolescence. They went to bed wearing Samp pyjamas. “We’re not friends, we’re brothers,” Vialli said, turning to Mancini. A band of them, keen to make mamma Samp and papa Mantovani proud.

It was a team that built gradually towards the Scudetto. Samp made eight finals in the decade after Mancini’s arrival, winning the Coppa Italia in 1985, 1988 and 1989 and UEFA’s old Cup Winners’ Cup in 1990.

Still, few people thought they could mount a genuine title challenge. Samp were up against Maradona’s Napoli, the Milan degli Olandesi — Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit, Frank Rijkaard — Inter’s World Cup-winning Germans Lothar Matthaus, Andreas Brehme and Jurgen Klinsmann, and Roberto Baggio’s Juventus. Winning the league represented quite a leap from the best Samp had achieved up until then, such as the pair of fourth-place finishes in 1985 and 1988.

Perish the thought, but had social media been around then, one can only imagine the narrative around these players.

“What’s Mancini doing there?”

“Vialli should go to a big club.”

Listing a few of the things I really can’t stand about football today, let’s start with how teams are broken up: the economic forces that pull players away; the end of loyalty and entitlement of supporters in other leagues who perceive a lack of ambition in a player who decides to stay where he is in order to do something great, historic, genuinely meaningful.

This version of Samp probably wouldn’t be possible today. The environment simply doesn’t allow it. The idea of a small club retaining a core of bright and talented players and building to this zenith makes the Sampd’oro years (Golden Samp) so precious as to strum at the nostalgic heartstrings in all of us.

The experience they developed together and their understanding of one another contributed to the improbable Scudetto of 1991.

Samp dared to do and defied the odds.

The players had been written off as eterne promesse, eternal and therefore unfulfilled promise. Moreover, they were thought of as spoilt and overly indulged by Mantovani. The kit man and capo ultra, Claudio Bosotin, even had cashmere football jerseys made for Vialli. The perception was annoying.

Then came Italia ’90, a home World Cup which wounded the pride of Samp’s stars. Vialli was eclipsed by the notti magiche (magic nights) of Toto Schilacci. Pietro Vierchowod, ‘The Tsar’, only played in the third-place play-off against England. Pagliuca and Mancini didn’t feature at all. The experience smarted and Vialli, particularly annoyed by it, picked up the phone and asked Mantovani for an extra week’s holiday to get over the disappointment. Such was the father-son relationship between Mantovani and his players, Vialli knew he’d be listened to.

But he made Mantovani a promise in return. Grant him the additional time off and he’d make sure Samp won the Scudetto that year.

The four of them came back to training more determined than ever. When Vialli tore his meniscus and missed the first couple of months of the season, remarkably it mattered little. Samp unexpectedly beat Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan, the champions of Europe, at San Siro through a goal from Cerezo, who would go behind the bar at the Overjoyed nightclub in Genoa and make everyone caipirinhas when the going was good.

Better still, Samp came back from behind to demolish Napoli, the champions of Italy, 4-1 at their Stadio San Paolo with a couple of sumptuous volleys from Vialli and Mancini; the first plucked out of the sky, the second on the run and off both posts. “Vialli’s two goals today were worth 20 because we’ve got the real Vialli back,” Boskov said.

Top of the table, the players organised a photoshoot of themselves dressed up as a class of goofy high-school nerds. Vialli appeared with his tie swept back over his shoulder, a helicopter hat on his head as if he were auditioning for a part in Napoleon Dynamite. Vierchowod posed by a chalkboard, the proudest of looks on his face, with “1st in A” written on it.

That was Samp. They didn’t take themselves too seriously and knew how to have a lot of fun, usually around a table in a local restaurant. They were inseparable and had several haunts. At La Piedigrotta, the players made a pact never to leave Samp until they won the league. At Edilio, the Seven Dwarfs, as the regulars were known, had a card game. At La Barcaccia, when results suddenly took a turn for the worse after a Branco free kick brought defeat in the Derby della Lanterna, they got whatever it was that was bothering them off their chests and cleared the air like a proper family.

It was not a completely happy family, regardless of Samp suddenly rediscovering that winning feeling and going undefeated for the rest of the season. Samp’s captain, Pellegrini, returned from injury but did not get his place back in the team. “Squadra vincente non si cambia,” Boskov told him. You don’t change a winning team. It was a brutal sacrifice for the Scudetto.

Ultimately, the decider came at San Siro in May against Inter in one of the most epic games of the era.

Samp came out on top, reacting better than their hosts to going down to 10 men after the usually pacific Beppe Bergomi and combustible Mancini were embroiled in a bust-up on the stroke of half-time. Beppe Dossena opened the scoring on the hour mark for the visitors, but the pivotal moment came a few moments later when Pagliuca, who had been unbeatable all day, thwarted the Ballon d’Or winning Matthaus from the penalty spot. Vialli then wrapped things up a short while afterwards, maintaining his composure in a tense one-on-one with ‘Spiderman’ — his good friend and international team-mate Walter Zenga.

A famous win, it sent Samp four points clear — the equivalent of two games in the old two-points-for-a-win era — with only three matches remaining. Mancini missed a couple of them, including the Scudetto clincher against Lecce at Marassi. He had hoped to get his ban commuted and even asked the priest at the church where the match officials used to pray when they were refereeing in Genoa to plead with them for forgiveness. But there was nothing doing.

He instead stood on the sidelines in his full kit, a giant tricolor held over his head, poised to run on the pitch at full-time of Samp’s 3-0 win over Lecce.

It was a Scudetto miracle. Unique in that it was Samp’s first and last. Nobody outside the big metropolises of Turin, Milan and Rome has won it since. Not even the best Parma side could do it. For all the fanfare about three Italian teams reaching the Champions League quarter-finals this season, remember Samp — yes, Samp — made it all the way to the European Cup final at Wembley the following year, losing only in extra time, to a free kick that should never have been given to Ronald Koeman and Barcelona’s Dream Team.

Samp did not go into that final in the right state of mind, either.

Vialli’s move to Juventus was leaking out. An underwhelming title defence (finishing sixth) foreshadowed a change of coach from Boskov to Sven-Goran Eriksson. The Sampgloria era entered its twilight and ended definitively with the death of Mantovani in 1993. Mancini has said he would never have left the club as long as he were alive.

The Scudetto year is revisited brilliantly in La Bella Stagione, a book turned into a film by Marco Ponti. It is a moving tale of friendship and I cried during the scene when Vialli revealed he hid his pancreatic cancer from Mancini. Except Mancini, of course, knew all along. Because of course he did. They were that close.

The film climaxes with their tearful embrace after Italy won the Euros at Wembley in 2021, a perfect redemptive circle, the Samp team-mates on Mancini’s staff — Lombardo, Fausto Pari, Fausto Salsano — dashing over to celebrate with them.

Italy was Samp over that glorious summer, which already feels so long ago, and Italy still needs Samp today.

We have passed from the Bella Stagione to the Brutta; the beautiful to the ugly one. Today, Samp are second-bottom of Serie A. They have been relegated before, most recently in 1999 and 2011, but not like this. In the last year, the owner, Massimo Ferrero, became the non-owner after he was arrested, sent to San Vittore jail, released on house arrest and then freed pending a committal hearing following investigations into a series of bankruptcies.

Lanna, the utility player in the 1991 team, was made president in the stormiest of circumstances. The club is held in a trust and has not been sold, angering supporters who have watched executives sell off the best players without replacing them and Claudio Ranieri walk out in 2021, the team sinking towards Serie B with each passing season.

Samp have struggled to pay the wages recently and, as the situation has become more and more desperate, pig heads and bullets have been sent to the club’s offices with threatening messages.

The famous lighthouse after which the Genoa derby takes its name will not be able to stop the club crashing onto the rocks. It’s a sorry state of affairs in what has been an awful year, with the passing of Vialli so soon after another fan favourite in Sinisa Mihajlovic.

For the love of Samp, in the hope of another Bella Stagione, may someone somewhere save the club.

Ben Radford/Allsport; Claudio Villa / via Getty Images. Designed by Sean Reilly)