Teen Titans Go: Young guns will decide NRLW Grand Final

You didn’t have to watch much NRLW action in 2023 to spot one of its most defining factors: everyone is really, really young.

Given the expansion of the competition to ten teams, and the rapid growth of women’s footy in the last five years, this is perhaps not surprising: the whole pathways system has been predicated on the maxim that if you are good enough, you are old enough.

It’s not just that you’re old enough to play, but that you’re old enough to get paid, too. The proliferation of young women in the NRLW – multiple teenagers per team – is proving just how quickly the comp has become a viable career choice for young players, who previously were without rugby league opportunities.

That so many have made it through is a huge vindication of the NRLW – and it should terrify Rugby Australia, who used to have the advantage in providing female athletes with the chance to go pro.

There was an argument that they once were the second best bet, behind cricket, but now, they trail the NRLW, AFLW and A-Leagues at a time when women’s sport has never been more prominent.

Much as the current inquest at RA HQ is into the poor performances of the Wallabies, they might find time to wonder how they have surrendered the women’s game entirely to the NRL, with bulk players switching codes and Wallaroos players in open revolt over their lack of access to professional facilities.

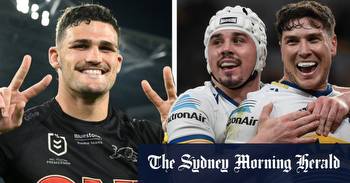

This weekend’s NRLW Grand Final has examples of how the pathways used to work and how they work now written all over the team lists.

Much as Knights’ teen sensation Jesse Southwell has been the focus of attention, making her second showpiece appearance at the age of just 18, the Titans are fielding four players who played in the Queensland under-19s Origin team.

Chantay Kiria-Ratu starts at five eighth, Destiny Mino-Sinapati on a wing while Sienna Lofipo and Rilee Jorgensen, a nominee for NRLW Rookie of the Year, will come off the bench.

So will Dannii Perese, who just missed out on that Origin team but is also a Titans sub, and Jacinta Carter, who played midyear, is 18th player for the Knights.Lofipo and Kiria-Ratu were the halves for the Maroons, Mino-Sinapati was the fullback and Jorgensen the lock. That’s the spine of the future, playing now, still in their teens.

If any of them need advice, they don’t have to go very far to find it. Georgia Roche, the English five eighth who partners Southwell in the halves at Newcastle, won the Woman of Steel for player of the year in the Super League at just 18.

That has worked at both ends of the spectrum, too. Steph Hancock, Niall Williams-Guthrie and Karina Brown – 40, 35 and 34 respectively – are all set to turn out for the Titans this weekend.

They’re older than anyone in the men’s final, where Adam Reynolds, 33, is the most experienced player, and Hancock and Williams-Guthrie are older than any male player across the whole NRL.

In the NRLW, with so many young players and such little accumulated experience, having a few wise heads around the place clearly helps.

The prevalence of youth in this year’s Grand Final likely speaks to the way that the NRLW pathways are working.

When Steph Hancock was 18, the Women’s World Cup was held in the UK, with little to no fanfare.

The players were not paid and, indeed, internationals were not officially recognised at all. Pathways? There were none.

Now, Hancock can look at the other three girls on the Titans bench at Accor Stadium with pride. Karyn Murphy, who played in that tournament, might do the same from the coaches’ box.

The explosion of young talent reflects the differing opportunities available now. The NRLW is in its sixth season, meaning that from the moment that the Titans teenagers began playing in high school, there has been an integrated pathway into paid footy.

For women’s footy players, this has been vital. The Titans will line up with two rugby union Olympians, Evania Pelite and Williams-Guthrie, who previously went through pathways in the other code that didn’t exist in league.

In total, ten union players have switched in this year alone – plus Sheridan Gallagher, who swapped Young Matildas honours for a Knights jumper and will line up this weekend.

Had they been younger, there’s a decent chance that all would have never left league in the first place, or, indeed, would have switched earlier due to greater opportunities to be compensated for their athletic talents.

It’s ironic that, at a time when Rugby Australia is willing to throw good money after bad in pursuit of male NRL talent, they have let their women’s game wither on the vine.

They have left all the advantages handed to them by the Olympics, which has featured Sevens since 2016, and by participation numbers that exceeded 4,000 ahead of the first Games.

Of the seven backs in that squad, five switched to NRLW: Pelite played in that team, as did Emma Tonegato, now one of rugby league’s highest paid women as captain at Cronulla, plus Charlotte Caslick and Ellia Green.

Three of New Zealand’s gold medal winning team are currently in the NRLW, too, including Williams-Guthrie.

There’s an interesting quote from Caslick, now 28, from prior to the 2016 Olympics, about the advantage that union had back then, before the NRLW existed when touch footy was about as good as most female players could hope for in terms of big-time rugby league.

“The pathways in rugby (union) were huge,” she told The Guardian. “Playing touch I’d pretty much done everything by the time I was 16. It was time to challenge myself with something new.”

Back then, there were almost no jobs for women’s rugby league players. Now, there are 300 contracts available, and the minimum gets more than all but the elite Wallaroos players.

Grace Kemp, who was a Wallaroo but is now a Canberra Raider, pointed this out earlier in the year.

“At the Raiders, I’m able to be an athlete – to go into (Canberra’s) centre of excellence and train and recover properly,” she told WWOS.

“We get physio, we get blood tests done monthly just to check in on our health, and that’s the difference between the [codes]. We’re supported off the field as well as on the field.

When the teenagers run onto the ground at Accor on Sunday, it’ll be tempting to point to their extreme talent and athleticism in getting to such a stage at such a young age.

But remember the structural reasons why they’re there, too. It’s all about cash, of course, in paying players and funding pathways, but also opportunities, and opportunity cost when those pathways aren’t there.

The likes of Pelite show what would have been possible if those pathways had existed in 2013, when she was 18, or even before than, in 2008, when she began high school.

With the NRLW, as with anything, there’s always room for improvement – and the line-ups on Sunday show just how quickly results can be seen.