The Horses Behind the Wildest Kentucky Derby Wins of All Time

(Bloomberg) -- It’s been 50 years since Secretariat rocketed past his overmatched rivals on the far turn at Churchill Downs and captivated a nation. The big red colt stopped the clock in record time that day: one minute, 59 and two-fifths seconds.

On a sheer brilliance scale, no other Kentucky Derby winner, before or since, stacks up.

But there have been, of course, countless great Derbies over the years. And we figured in the run up to this year’s race — to be held this Saturday — the 50th anniversary of Red’s exploits makes as good a time as any to look back at those classics. We picked out a half-dozen of them. Some are more about the backstory, or the aftermath, than the race itself.

The first of them dates back 108 years, when a striking chestnut filly with a big white blaze on her face walked into the starting gate at Churchill Downs and put the Kentucky Derby on the map.

Regret, 1915

The tycoon Harry Payne Whitney named his young filly Regret, it is said, because he had really been hoping for a colt. He’d soon eat his words.

Regret was majestic and powerful and brilliantly fast from a very young age, and so in the summer of 1914, she was sent to Saratoga Springs, New York, to make her racing debut in front of the East Coast’s fashionable set. There, in the span of just 15 days, she thrashed the best young colts three straight times. Nine months later she’d do it again in Louisville, bolting out to a quick early lead against her 15 rivals in the 41st running of the Kentucky Derby and holding them off so effortlessly that her rider eased her up in the final yards.

Her victory over the boys captured the attention of the press all across the country and, in the process, turned the Derby into the marquee national sporting event it is today. Only two other fillies — Genuine Risk in 1980 and Winning Colors in 1988 — would subsequently win the Derby, but that’s largely because fillies are rarely given the chance. At 8%, their win rate in the Derby is identical to that of the boys.

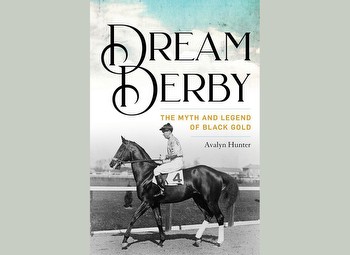

Black Gold, 1924

This story starts in Juarez, Mexico, where a man by the name of Alfred Hoots found himself in a bind.

Hoots had brought his talented and rugged mare, Useeit, over the border to earn some much-needed cash in a low-level race to take back home to Oklahoma. Only problem was, per the rules of the race, Useeit could be bought by any horse owner at the track that day and, lo and behold, she was. Hoots loved the mare and wasn’t about to part with her. So when the new owners came to pick Useeit up, he whipped out a shotgun to keep them at bay and escorted her back over the border.

Mexican officials were furious. They banished Hoots from racing in the country, but he didn’t care. He had his horse. A year later, Hoots fell ill, and on his deathbed, he urged his wife, Rosa, to breed Useeit to a champion stallion named Black Toney. He was convinced — and this part feels a touch apocryphal — that the offspring would win the Kentucky Derby.

The Hoots clan was, though, pressed for cash, as always, and breeding Useeit to a blue-blooded stallion was out of their reach, according to the journalist Winston Groom. Until, that is, oil was discovered on land they leased in 1919. The very next year, Rosa sent Useeit to Kentucky for that mating with Black Toney. Four years later, their son, a jet-black colt named Black Gold, hit the finish line first in the Kentucky Derby.

Dark Star, 1953

Native Dancer was supposed to win the Derby and win it easily. He was fast, imposing, royally bred by his owner, a scion of the Vanderbilt dynasty, and wildly popular with Americans because his gray coat made him easy to spot on their brand-new black-and-white TVs. The “Grey Ghost” arrived in Louisville undefeated that spring, having racked up 11 straight wins.

But on this day, he ran into traffic on the first turn, got banged around and found himself chasing a 24-1 long shot named Dark Star. Native Dancer made a furious late rally but came up just short, beaten by a head. It would be the lone blemish in his 22-race career.

Canonero II, 1971

Purchased out of a Kentucky auction ring for a mere $1,200 by a Venezuelan businessman, Canonero II was soon whisked off to Caracas. He established himself as a top colt there, and so the owner, feeling enterprising, decided to send him back to Kentucky to try his luck in the Derby.

His journey was an odyssey. His first two scheduled flights from Caracas to Miami were forced to turn back; on the third flight, he was crammed into a cargo plane alongside crates of ducks and chickens, according to the author Laura Hillenbrand (Seabiscuit: An American Legend). When he arrived in Miami, his handlers didn’t have the paperwork needed to get him through customs, and he was stuck in the sweltering heat for days. Once cleared, he was loaded onto a van for Louisville. It promptly broke down.

By the time the horse finally got to Churchill Downs, he was frazzled and gaunt. The Kentucky hardboots and the press snickered at him and his Venezuelan trainer’s unusual methods. But Canonero II thrived in Louisville and when race day came around, he was ready to roll. He dropped to the back of the pack at the start and then, in a rush, stormed past the field to win going away. The crowd, Hillenbrand says, fell dead silent.

The 17-1 odds don’t reflect it — back then, all the big Derby long shots were pooled together into a single betting entry — but his victory was perhaps the most shocking in the race’s 148-year history.

Secretariat, 1973

The horse has become so deified over the years that it can get tedious at times, but the truth is he really was that good. Not only has his Derby time held up all these years later as the fastest ever, but so have the times he posted in the Preakness Stakes and Belmont Stakes, a jaw-dropping, 31-length romp. There were more consistent horses, like Native Dancer, but none was faster than Red.

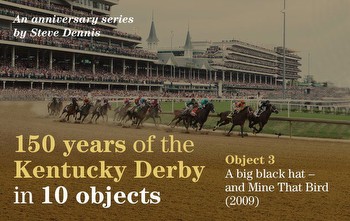

Mine That Bird, 2009

There was nothing that suggested Mine That Bird had a shot at winning the Derby when his trainer, Bennie “Chip” Woolley, started hauling him across the country to Louisville. The horse was so runty and bland-looking that he had fetched only $9,500 at auction two years earlier. And his pedigree was so unfashionable that his owners castrated him — eliminating any chance of a lucrative post-racing career in the breeding shed — to try to coax better races out of him.

Mine That Bird had some success early on in his career but sputtered badly when put up against top horses. Six months before the Derby, he ran dead last in the Breeders’ Cup Juvenile. Sent to the mountains of southern New Mexico, an obscure stop in the national racing scene, and turned over to Woolley, an eccentric character perennially decked out in a big black cowboy hat, his first two races in 2009 were mediocre at best.

So when Woolley and Mine That Bird pulled into Churchill Downs, after a 1,500-mile drive, no one paid any attention. Derby day, though, brought heavy rain that turned the track into a muddy mess. And there is an old racetrack axiom that says little horses run well in the mud. Their light frame, the thinking goes, prevents them from bogging down in the muck like the bigger colts do.

Mine That Bird’s Derby is Exhibit A of that theory: He fell back to last early and then skimmed his way along the inner rail all the way to the lead, hitting the finish line an astonishing 6 3/4 lengths in front. It was the biggest margin of victory in a Derby in almost 100 years, and Mine That Bird’s backers were rewarded with a 50-1 payout. The horse would never win another race again.

Mandaloun, 2021

Mandaloun did not cross the finish line first that day. Trainer Bob Baffert’s little colt, Medina Spirit, did. But days later, Medina Spirit tested positive for a banned raceday medication, triggering a scandal that engulfed Baffert, the biggest star in American horse racing, and ultimately led to the colt’s disqualification.

Mandaloun, the runner-up, was elevated to first. This marked the second time in three years that the first-place finisher in the Derby was not awarded the winner’s trophy — something that had only happened once in all the years prior. (Maximum Security was disqualified in 2019 after banging into rivals.)

Today, Baffert, who’s won a record-tying six Derbies, is still on the outside looking in, waiting for his suspension from the race to end. And Medina Spirit’s remains lie in the ground in the rolling bluegrass fields to the east of Louisville. Months after the Derby, he went out to the track one morning for a routine workout, cruised past the grandstand and dropped dead.