Vintage St. Pete: What’s to become of Derby Lane?

The dogs don’t run at Derby Lane any more. There hasn’t been a documented canine on the premises since the tail end of 2000, when Florida’s Amendment 13, banning greyhound racing in the state, took effect.

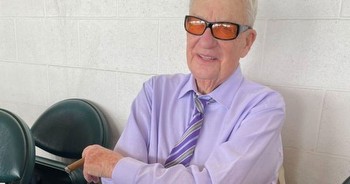

By then, Richard Winning had been President and Chairman of the Board of the St. Petersburg Kennel Club Inc., the track’s official company name, for five years and 11 months. This after working just about every job at the place since the mid 1970s; he even studied dog training and handling, although as an administrator (and a member of the family that owned Derby Lane) he didn’t have to.

Derby Lane had been running dogs, right there on Gandy Boulevard, since 1925. It proudly billed itself as The Oldest Continually Operating Greyhound Track in the Nation.

When all that went away, after his five years as top dog, it wasn’t sour grapes for Richard Winning.

It had more of a citrus flavor, actually.

“When they give you lemons,” he says, “you gotta learn to make lemonade somehow.”

Richard Winning is a glass-half-full kind of guy.

A great-grandson of Derby Lane founder T.L. Weaver, the 67-year-old Winning now finds himself head of an empire long past its glory days. The quarter-mile track has been filled in with grass, the electronics odds board stripped of bulbs and wire, and the only sounds in the grandstands come from gusty afternoon winds.

But there’s life in the Derby Club building, every day, with visitors playing poker, Vegas-style (the state legalized poker at parimutuel betting centers like Derby Lane in 1996) and wagering on simulcast greyhound races from the only state (West Virginia) where it’s still legal. Along with horse races from all over the country.

The place is well-maintained, and still looks like a million bucks.

It sure isn’t like the peak years, the ‘80s for example, when 10,000 people would pass through Derby Lane’s turnstiles on a summer’s night, going ga-ga over a speedy pup (and consistent winner) named Keefer. In Keefer’s prime, in 1986 alone, $105 million was wagered at Derby Lane – a track record. The fine dining restaurant in the Derby Club was famous for its prime rib – ceiling-high viewing windows overlooked the track.

These days, the poker and the simulcasts, and the leasing of the city-sized parking lot to businesses like Amazon, which uses it as a truck-staging area – pay the bills and keep the 300 employees coming back.

“Fortunately,” Winning says, “we didn’t have to just shut all of our doors. It would be hell if they put you right out of business.”

“They” being the animal rights groups who pushed Amendment 13 through. Greyhound racing, they insisted, was cruel and inhumane to the animals.

The most vocal of these groups, GREY2K USA, publicized shocking statistics about mistreatment of racing dogs, kennel and track injuries and euthanasia when the dogs were hurt or had aged past their prime.

Florida was among the states that did not require dog tracks to report these things; there are no official records of injuries or deaths at Derby Lane.

“I think they sensationalized the statistics,” Winning declares. “Yes, a track may have had problems; they make it sound like all the tracks had that problem. And they focus on one: ‘Oh, they injured so many dogs at this track.’”

There are injuries in horse racing, aren’t there? he asks. Athletes, animal or human, will get hurt.

“Well, if you’re racing 300 days out of the year, and you’re running 15 races a day, in the end what have you got? You got a lot of starts, and a lot of dogs running – it’s like a kid going out and playing soccer. Yeah, they could go out and play football and break their leg. But they don’t sensationalize football injuries.”

No dogs actually lived at Derby Lane, although the company did briefly operate an off-site kennel. Their handlers brought them there on race days, to gallop like racehorses after a fake rabbit mounted on a fast-moving mechanical track.

Winning has few kind words for the animal rights people who nearly cost him his livelihood. “We had 1,500 dogs, and 700 of them were on the active list at any given point,” says Winning. “And they’re racing twice a week. But when you figure a guy pays anywhere from $5,000 to $70,000 for a dog, it’s not like he’s going to abuse him or anything. Are you kidding me?”

Facts, however, are facts. And the activists won the war.

If he closes his eyes, he can still see the dogs, and the lights, and the grandstands packed with people.

“I miss the excitement of the race,” Winning admits. “The roar of the crowd. People are just cheering, and screaming … when the greyhounds broke out of the starting box, and went into that first turn, they were doing better than 45 miles an hour.

“The whole race was done in 30 seconds – and you don’t realize how long that is until you try to stand to one leg for 30 seconds.”

That’s all water under the paddock now. Derby Lane sits on 130 acres of prime county land, most of it parking lot, two of its three massive buildings sitting boxlike and empty.

And they’re off!

The story starts with T.L. Weaver, a “lumber baron” in the county’s formative years. In 1923 he sold 130 acres of scrubby pine forest just north of St. Petersburg proper to a group of local entrepreneurs; Weaver even built the wooden grandstands for their rudimentary greyhound track.

But they couldn’t pay him, so the legend goes, and ceded the property – and the business – to T.L. Weaver, who overnight became the godfather of Florida greyhound racing. The first races were run at St. Petersburg Kennel Club, as it was called, on Jan. 3, 1925, with 4,000 people in attendance. St. Petersburg was still a “winter” city, so the Kennel Club – like most of the hotels – closed up in the warmer months.

1931: Florida legalizes parimutuel betting, wherein those who have bet on the winners of a race share in the total amount wagered (i.e. they split the entire pot, with management taking a cut, naturally). Prior to this, all gambling was illegal in Florida; track owners “sold shares” in the dogs as a way of getting around the law.

1949: Following the war years, when gambling had been temporarily abolished, Derby Lane officials begin planning a bold new future.

“For a quarter of a century, lacking a year, greyhound racing as presented at the Kennel Club has been St. Petersburg’s major all-winter sports attraction,” E.L. Weaver declares in March. “We believe that greyhound racing at our plant has played a vital part in attracting thousands of visitors to the city annually – and in entertaining those visitors and the year-around residents as well.”

Weaver spends $500,000 to replace the original wooden grandstands with state-of-the-art concrete and steel benches on two cantilevered levels, with heating for cold nights; he installs a paddock for weighing and dressing the dogs, a lighted odds board, and a bandshell on the field.

And he announces a new name: Derby Lane. This will be emblazoned in lighted red letters, eight feet high, across the back of the grandstand facing Gandy Boulevard.

1966: The seven-story Derby Club building, with massive viewing windows overlooking the track, opens April 1, during the city’s annual Festival of States celebration. The lower levels adjoin the main betting area beneath the grandstands. The facility includes “three betting levels, two of which are enclosed, two cocktail lounges, box seats, five terraces of tables, escalators and high-speed elevators.” Guests for the grand opening are Festival of States “royalty,” Mr. and Mrs. Sun Goddess. Restaurant service in the Derby Club will commence soon and remain a popular feature for decades.

1974: The old clubhouse building is demolished, and in its place rises the modern Plaza Building.

1975: Richard Winning, who’s studying business at the University of South Florida, begins working at Derby Lane. His first job is emptying quarters from the turnstiles.

1986: Keefer, a Kansas-bred “All America” greyhound, becomes Derby Lane’s all-time single season winner (23 races). People start showing up just to watch him run.

1987: It’s Keefer-mania at the track. “The Elvis of dogdom,” the 83-pound champion is dubbed by St. Petersburg Times columnist Tom Zucco. Derby Lane sells Keefer T-shirts, “autographed” photos and bobbleheads. And a record crowd of 12,779 cheers him on when he easily wins his second consecutive Distance Classic (purse: $100,000) Feb. 21. Even the Wall Street Journal runs a story about him.

1988: Introduction of the Florida Lottery. This, Winning believes with the benefit of hindsight, was the true beginning of the end. “You go to Publix or 7-Eleven, you get your cards, you scratch off … we were the first racetrack to allow lottery sales. We cashed twice of what we sold.

“The thinking at the time was, why have ‘em go home on Friday night with their paycheck, get their beer at 7-Eleven, buy a ticket and go home? If they know they can come to the track, and buy a ticket out here?”

1997: Derby Lane introduces poker.

2003: Debut of Tampa’s Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino. Winning: “That’s when you started seeing it going down. And then the animal rights issues started taking off. One thing leads to another. And now the Seminole Tribe owns the state of Florida, so what’s the difference?”

2014: The Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation, Division of Pari-Mutuel Wagering reports that the amount gambled at dog tracks declined by 72% between 1990 and 2013.

2015: Senior vice president Richard Winning is named president and board chairman of St. Petersburg Kennel Club Inc., when his cousin Vey Weaver retires in May.

2018: Florida voters pass Amendment 13, which calls for the abolishment of greyhound racing in the state by the end of 2020.

2020 (Dec. 27): The final race.

The last lap?

Greyhound racing was once the sixth most popular spectator sport in the United States. In Tampa Bay, before the Buccaneers, the Rowdies or the Rays, Derby Lane was the epicenter. The sports pages of the St. Petersburg Times were filled with profiles of dog owners and dog trainers (and dogs) for half a century. Always, every day, the newspaper published stats and race results from Derby Lane.

Nearly three years after what they did was pronounced illegal, Winning and his board of directors are doing what they can to avoid freefall. The name has been “officially” changed to Win! Derby, although the massive ‘40s-era sign still advertises DERBY LANE to motorists passing by on Gandy.

“It’s paying for itself,” Winning declares, “but it’s tight, because it costs a lot of money to crank this thing up. We got a lot of building here. With taxes and everything else, they’re not easy on us. Even though we’re still here. And we’ve got to produce something.”

Derby Lane is in what’s called a Coastal High Hazard area, which means it’s susceptible to flooding. This makes any potential land sale problematic, as prospective buyers fear governmental limits on what they can potentially build. They use it as a bargaining chip.

“That happens all the time,” Winning says. “People just want to get some land and get it cheap.

“So, how do you put a price on it? I refuse to just stick a ‘For Sale’ sign out there and name a price. That’s not it. There’s a big chunk of land here, right in the middle of the county in a great location.”

Still, the facts must be faced. Something’s got to give, eventually.

“We won’t be here forever; we’ll have to tear this thing down. We’re going to have to build another building, somewhere on the property. Build a smaller facility. We can get a lot more efficient with a smaller facility in an area tucked off the side somewhere.

“Then you’ve a big place here you can look at and say ‘OK, now what do we do?’”