Where are they now?: Brian Cusack

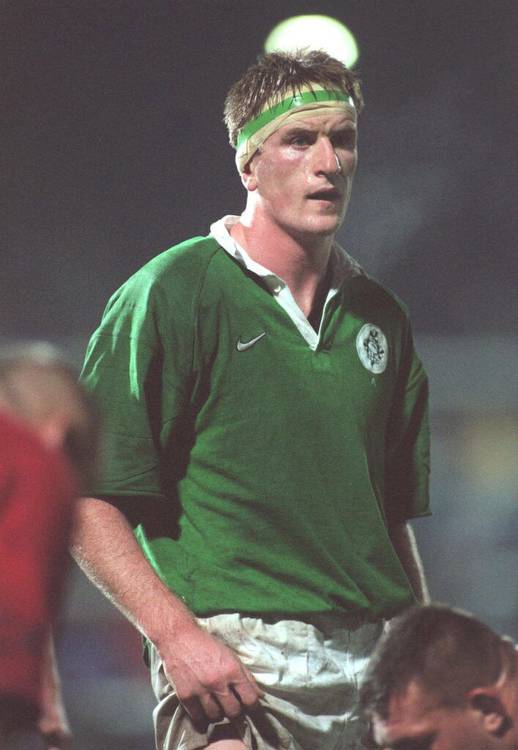

THEN – Brian played for Leinster in two stints between 1994-1996 and 1999-2000.

NOW – He is Head of Trading at PointsBet, living in Eadestown in Kildare with his wife Heather with two girls Lauren (12) and Alex (10).

It wouldn’t happen these days.

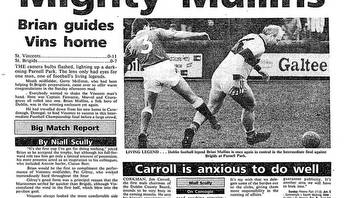

Back in 1994, Brian Cusack had just gone through 80-minutes of All-Ireland League action for Bective Rangers.

The thirst to unwind and relax usually started by settling in for a scatter of pints in the clubhouse bar.

On this occasion, a tap on the shoulder was followed by an invitation to make his debut for Leinster against The Exiles at Donnybrook the next day.

He put his drink down and went home for an early night.

“I was training with the national squad at that stage as one of the youngsters, purely used as a tackle bag handler,” says Brian.

“There was a lot of experience in the Leinster team at that stage with ‘Franno’ (Neil Frances) playing in the second row Phil Lawlor at number eight, Alain Rolland at nine. Props Angus McKeen and Henry Hurley were there too.

“It appeared to me to be a late decision to drop me in there from the start to see how I would go and it turned out to be a great experience.

“Probably, in the early days, playing with big personalities, you just wanted to survive rather than putting your best foot forward and having the utmost confidence in your ability to impact the game.”

In 1990, on the basis of Clongowes Wood’s run to the Senior Cup final, Brian made his way into the Ireland Schools squad where Neil Nolan and Roger Wilson stood in his way.

The Ireland U21s gave Brian the chance to play alongside Gary Longwell in 1992-1993 and Jeremy Davidson in 1993-1994 in the second row.

This was long before the Leinster Academy swung into view, even before the Irish Academy started.

Thus, the muck and bullets of the All-Ireland League served as Brian’s true apprenticeship in dealing with the tricks of gritty, gnarled veterans.

“I went straight into the first team at Bective where Ireland internationals Kurt McQuilkin and Phil Lawlor were playing,” he says.

“The club was in Division Two of the AIL. We also had a group of experienced heads, like Maurice Mortell, and Trevor Brennan arrived the next year.

“We had a very good side, good enough to be in the lower half to be competitive in Division One, I would say,” he states.” But we couldn’t make the next step.

“You did your own rugby work on Monday and Wednesday, trained with the club on Tuesday and Thursday and played on Saturday.

“You learned the grizzly old way of playing every week. You picked things up as you went along, often getting beaten up by the older, more mature players in what was an old-school apprenticeship.

“You were purely amateur. There were certainly people at Bective, who would help you along and they brought in Doctor Liam Hennessy. to support that development.

“There are a lot of people like Liam around now. Back then, he was one of the few who knew the why behind what he was doing, bringing his experience from athletics and his academic background.

“If you ask me ‘who were the first players to come through to be properly strong early adopters of strength training?’

“It would have been Jonathan Bell and David Corkery. When you played against them, you knew they were properly strong people.”

Brian’s long, lean 6’7” frame did not accept muscle readily, although there was an advantage in athleticism.

“The bigger, heavier guys tended to last longer But, this was pre-lifting weights. You could get away with not having the muscle back then. Could you get away with it now? No, you just can’t.

“It was when you came up against players who were bigger and athletic that you ran into the possibility of being dominated.”

Gabriel Fulcher became a person of interest to Brian in that the fellow second row wasn’t the biggest lock in the world.

“‘Fulch’ was quite clever in what he did and he was one I would watch to see how he did it. I saw him as similar to me as a player, someone I could learn from.”

In February of 1995, he partnered with Malcolm O’Kelly in the engine room against Northern Transvaal, getting a glimpse of the shape of things to come, in terms of personal competition.

“Mal was just a fantastic athlete with a massive engine and one of a limited number of really top-class players we have reproduced over the years. A great fella too.

“You see him in operation – he was slightly younger than me – and you realise, ‘oh, this is what is coming.’”

The game turned professional in 1995 and the Irish Rugby Football Union did not exactly embrace it immediately.

“Back then, in my experience, you didn’t know what professionalism was until you had been through it. It was only then you knew what was required.

“In 1996, It just meant you got paid and had more time to train,” he shares.

“But, there wasn’t anything smart about it because no one had gone through it. You trained harder and took contact four or five times a week. That would be unheard of today.

“You certainly got bigger and stronger and faster. That was clear early on when you went full-time. Your statistics went through the roof because you could train, rest and recover.

“Did our diets change? Not particularly. The support structure around that was very limited. I would say it took at least 15 years for proper professional structures to be put in place.

“When the players come in these days, everything is in place for them. There is a long history, maybe 20-odd years, of getting it right.

“In that time, the good and bad decisions taken and lessons learned have led Leinster to where they are, right at the top of the professional game.”

In 1996, Leinster was uncertain of where the game was going, and Brian took an offer to play for English kingpins Bath, leaving his job as a mortgage broker for a significant pay rise.

“There was no decision to be made really. Leinster were trying to figure out how they wanted to handle professionalism and Bath were just further down the road.

“Clubs were moving extremely quickly,” he says.

“When there is no organisation, there tends to be a vacuum and all the English clubs were trying to put businesses together overnight, put structures in place, put people in place, scale the clubs up into success.”

Brian signed a one-year contract and stayed for 2 ½ years, playing with Mike Catt, Jerry Guscott, John Mallett, Victor Ubogu, Federico Mendez, Nigel Redman, Martin Haag, Andy Robinson, Gary French and Steve Ojomoh at The Recreation Ground where they won the Heineken Cup in 1998 while he was there.

He moved to Richmond for seven months only for the club to go into administration in the same way Wasps and Worcester have fallen apart.

In 1999, Jim Glennon and Mike Ruddock reached out and Brian returned home to play one more season with Leinster, his final cap coming off the bench against Munster.

“There had been changes. But, it was still back in the dark ages, playing out of portacabins in Anglesea Road. It wasn’t overly glamorous.

“At that stage, I played for Lansdowne and I found the clubs were better organised than the provinces.”

Now Head of Trading at PointsBet, he found the benefits taken from rugby into his post-playing career matched by the costs he had to shake.

“There are some really good things you can take into your career and some really bad habits you have to change,” he warns.

“Creating a good atmosphere for people to work to their optimum ability, that does take time to get right.

“Some sporting teams have it; some struggle with it. It can take a couple of years, in rugby and in business, to get it right.

“The hard thing is getting to that place. Once you are there, it is easier to keep it going.”

“However, he traced back negatives accrued from rugby that had to be overcome

“Things don’t get fixed overnight like they do in rugby,” he adds.

“Stuff goes on on the pitch, you fix it quickly and bluntly for the following week. That doesn’t work in business. Often you need to be more patient.

“The right tone of communication is really important and that is not something rugby is good at because it is not needed.

“On a Monday, a rugby player takes really harsh, brutal criticism as a platform to learn from. Generally, you can’t do that with a team in business.

“Criticism needs to be delivered constructively and encouragingly.

“Even in rugby now, Eddie Jones got away with a brutally hard regime because he was having success. When that success stopped happening, it came back to bite him.

“You need to bring people along with you. Your tone and ability to communicate well are really important.”