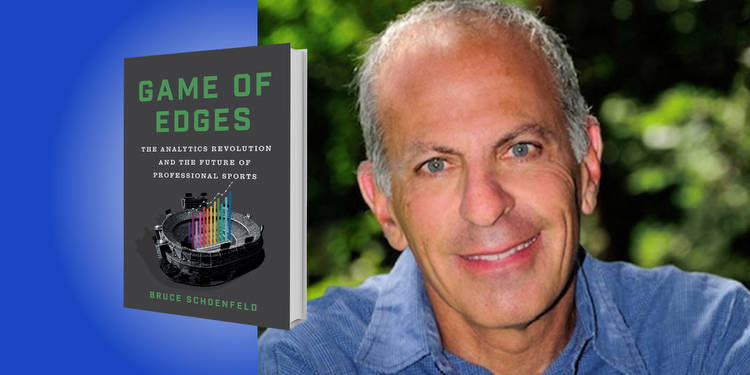

Game of Edges: The Analytics Revolution and the Future of Professional Sports

Bruce Schoenfeld is a magazine and television journalist. He is a frequent contributor to the New York TimesMagazine, Sports Illustrated, and Travel & Leisure. He won Emmy Awards for his writing on the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul and the 1996 Olympic Games in Barcelona.

Below, Bruce shares five key insights from his new book, Game of Edges: The Analytics Revolution and the Future of Professional Sports. Listen to the audio version—read by Bruce himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Sports teams aren’t toys anymore.

Throughout the last century, most sports teams were basically baubles for rich people. Few owners made their living off their teams, especially in the early days of professional sports. But then most of them existed as a tiny piece of a larger portfolio. In the mid-90s, Bob Tisch paid $75 million for half of the NFL’s New York Giants. Tisch owned Loews Hotels, Lorillard Tobacco, and had plenty of other interests. He stated that he didn’t care if the Giants ever turned a profit, and in fact, he was going to pretend he’d never had that $75 million.

A few weeks ago, the private equity investor Josh Harris agreed to spend more than $6 billion to buy the Washington Commanders. Harris is rich, but not so rich that he can pretend he’d never had that $6 billion. For that record-setting sum, he and his partners are getting not just a sports team but the equivalent of a mutual fund of interests. The Commanders encompass entertainment, not only through the football games they play every weekend but also television programming and internet content—both of which add incremental revenue. There’s hospitality and catering, clothing and other retail items, sponsorships and advertising, and even potentially real estate if Harris is able to build a new stadium.

The scale of operations has become so vast that a team like the Commanders, or any other big-league team, can no longer be run capriciously, as a toy. Instead, it needs to be optimized using the same data collection and analysis and other best practices that most $6 billion companies use. Increasingly, this is happening throughout sports, and there are both positive and negative ramifications.

2. Analytics helps teams, but can harm sports.

Beginning in baseball, and then in basketball and other major sports, the use of data analysis gave teams the chance to overperform. Usually, these were teams that were underfunded compared with their large-market rivals; teams that weren’t likely to win championships utilizing traditional tactics. Often, these teams had owners who’d made their money in finance, as fund managers or private investors or venture capitalists, in which the use of analytics and the application of best practices was routine. These owners understood that challenging, preconceived notions about player value and strategies gave them an edge over teams that didn’t.

Eventually, it became clear that much of the received wisdom that coaches and general managers had taken for granted for decades was no longer valid, if in fact it had ever been. From the quirky beliefs of a few cutting-edge teams, many of the analytics-based insights were adopted across their sport. In baseball, teams stopped bunting. Accepted statistics such as batting average and wins, the basic currencies used for player evaluation for generations, became far less important than new metrics like Runs Created and Wins Above Replacement.

“It turns out that the best way to play these sports isn’t necessarily the most entertaining.”

In basketball, hidden talents such as Kentucky’s Rajon Rondo, who didn’t score particularly or pass all that well but rebounded a lot for a guard and tended to get fouled frequently, became unlikely first-round picks and championship contributors. When some of the smartest European soccer teams applied data-based values to everything that happened on the field, they learned that taking long shots didn’t make sense, but signing players who routinely attempted certain kinds of ambitious passes did.

It turns out that the best way to play these sports isn’t necessarily the most entertaining. In this optimized version of baseball, for example, the amount of time between balls put in play is far longer than it was before, what with all the walks, homers, and strikeouts. Those outcomes proliferated, at the expense of doubles, triples, stolen bases, and great fielding plays.

Most worrisome, the heroism of individual players had little value in a landscape ruled by probabilities. So, even though Tampa Bay’s Blake Snell was pitching a masterpiece of historic proportions in the 2018 World Series, that didn’t prevent manager Kevin Cash from removing him the third time around the Dodger lineup because it was based on the knowledge that pitchers were nearly always less effective by then. The fact that much of America was watching the game to see exactly that kind of performance didn’t enter into his calculations. Clearly, in the translation of baseball from a game that relied on instincts and emotions to one governed by data, something had been lost.

3. When sports become homogenized, they lose some of their appeal.

After leagues started scaffolding franchises from losing money near the end of the last century and big-league sports stabilized, even the least successful franchises started doing perfectly well economically. Some were making money; some were treading water; but you could always sell for a huge multiple of what you’d paid. Still, the old-school owners, who’d made their fortunes in grocery stores or shopping malls, were leaving revenue on the table. As sports teams grew as businesses, it became clear that they were leaving a sizeable amount.

The businessmen who were getting really rich in late 20th Century America weren’t the manufacturers and company owners of the previous generations. Rather, they were investment bankers and fund managers whose special skills involved using numbers to find an edge. As they turned 40 or 50 with enough money to last them the rest of their lives, they started buying sports teams. It seemed natural to run them in the same way that they’d run those companies. So they used data to identify optimal ticket pricing, and what time games should start. They tracked every purchase at the concession stands, weeded out the slower-selling items, and promoted the favorites. They measured which of the songs they played during timeouts or between innings got the fans singing and shouting, and then played only those songs.

“Part of what we love about sports is its individuality and the uniqueness of our experience.”

If everyone is doing something optimally, they’ll all end up doing it the same way. That kind of homogenization is fine in most categories. You want every Apple Store or Pizza Hut you visit to feel familiar and comfortable. However, part of what we love about sports is its individuality and the uniqueness of our experience. When the music at Knicks games comes from the same crowd-tested, league-sanctioned playlist as the music at Pistons and Jazz games, and when those same songs are played night after night, the experience comes dangerously close to feeling generic, and over the long term, generic is definitely not optimal.

4. Leagues embraced gambling to feed the beast.

In 2018, the need to keep generating the scale of revenue that billion-dollar businesses require to thrive led the professional leagues to abruptly reverse their century-old distaste for sports gambling. The internet, coupled with the wide distribution of hand-held devices, meant that bets were no longer limited to which team would win, and by how much. Fans could now put money down once games had already started, enabling them to create a vested interest in who would score the next goal, or which team would score the most points in the fourth quarter.

This was crucial for sports leagues because previously, the tail-end of all but the most competitive games were useless inventory. Rather than switch off a basketball game in which one team was ahead by 20 points in the fourth quarter, a fan could bet on which team would score the most from that point forward. That turned what had been termed garbage time into crunch time, and kept ratings high for the most uncompetitive of games. Adam Silver, the NBA commissioner, explained it this way: if he could take the roughly billion people globally who were already watching NBA games and convince them to watch 10 minutes more of each, it was by far the most efficient way to grow the business.

“If you have a bet on which team will win the fourth quarter, you are no longer aligned with the players, who only care about whether they win the game.”

However, bets meant that a fan would be a step further removed from the games they were watching. If you have a bet on which team will win the fourth quarter, you are no longer aligned with the players, who only care about whether they win the game. Betting on how many curveballs will be thrown in the fifth inning becomes a step even further removed than that. When DraftKings created a fantasy league from non-fungible tokens in 2022, it allowed bettors, sorry investors, to buy a portfolio of players without necessarily knowing who any of them were. That’s great for DraftKings, and even, in the short term, great for the NFL. However, whether these investors would ever become interested in the actual games or develop loyalty to one of the teams that were playing them remains to be seen.

5. Pro-sports sits at a crossroads.

Analytics has a seductive narrative. How can you not like the idea of finding a better way to do something right there in plain sight that we all thought we understood? But at the same time, so much of the appeal of sports is its context—the history, lore, and cultural trappings that give it resonance far beyond a bunch of athletes playing a game year after year.

Going forward, the challenge for the pro sports leagues in North America and beyond is to find a way to unify these two divergent perspectives. If you push back against changes in the sport you love, from new rules to uniform patches to games moving off free television to internet streams, you’re disdained as a backward-looking purist. Yet the unmooring of sports from their context for short-term appeal is clearly a perilous strategy, and one that seems to be alienating older fans and failing to engage younger ones.

The men (and a handful of women) who own big-league sports franchises are undeniably smart. They preside over a glorified pastime that has become a wildly profitable industry. In the coming years, we will find out if they are wise.

To listen to the audio version read by author Bruce Schoenfeld, download the Next Big Idea App today: