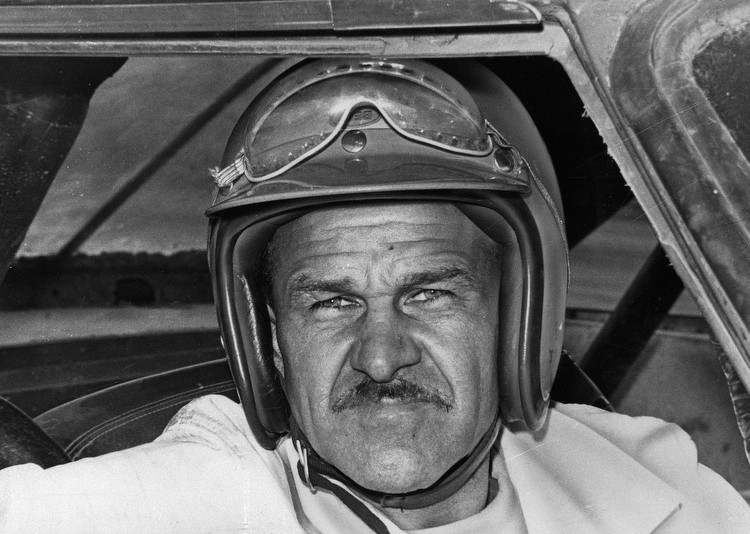

Wendell Scott, first Black NASCAR driver, beat the odds-and competition

Sliding around the turns, tires kicking up dirt, Wendell Scott’s pale blue ’62 Chevy was handling better than his competitors’ rides. Just ahead of him in first place was Richard Petty, driving a bright blue Plymouth.

The date was Dec. 1, 1963, and the heavily rutted dirt oval track of Speedway Park in Jacksonville, Fla., had taken out several drivers with broken wheels and axles. Then, with 25 laps left in the 200-lap race, it was Petty’s turn, as the track damaged his vehicle’s steering arm. Scott took the lead.

But he got a shock when he looked up at the scoreboard, which usually listed the numbers of the cars in the top five positions: All the numbers had disappeared.

When Scott finished the final lap ahead of the other drivers, there was no checkered flag to signal the end of the race. Though Scott had just made history as the first Black driver to win at NASCAR’s top level, his achievement wasn’t initially acknowledged. Instead, the checkered flag, trophy and victory-circle celebration went to Buck Baker, the second-place finisher, whom Scott had lapped twice.

NASCAR officials were reportedly concerned about how a White crowd would react to a Black man kissing a White beauty queen in the victory circle, as was customary for the winning driver. It was only after the race was over and the crowd had left that Scott was declared the winner.

The incident was par for the course for Scott, NASCAR’s first Black driver and team owner. A native of Danville, Va., Scott saw his racing career marred by racial prejudice, manifesting in death threats, slashed tires and deliberate attempts by competitors to wreck his car. Still, he managed to achieve 147 top-10 finishes in 495 career Grand National starts and finished in the top 10 annual standings for four seasons.

“My father was one of the vanguards of NASCAR history,” said Wendell’s son Frank, who served as part of his racing team along with his six siblings. “With a shoestring budget and all of that other adversity that we dealt with during those years, during the Jim Crow South, his legacy is amazing.”

Through his fierce determination, skilled driving and mechanical talent, Scott was a trailblazer and one of the top drivers of his era,but he’s still largely unknown outside of racing circles.

That might be starting to change. More than three decades after his death, amid a nationwide racial reckoning and the continued advocacy efforts of his family, Wendell Scott is finally beginning to get his due.

If you grew up in Danville in the 1920s and ’30s, you generally had to decide between two lines of work: milling cotton and processing tobacco. Scott wanted neither.

At an early age, he began learning auto mechanics from his father. After serving as a mechanic during World War II in Europe, he returned home and opened a car repair shop. To make ends meet, he took up running moonshine, a dangerous and illegal endeavor. Like many racers of his era, including Baker, Junior Johnson and Curtis Turner, Scott transformed the driving skills he acquired by running moonshine into a racing career.

After being indicted for moonshining in 1949 and sentenced to three years’ probation, Scott was approached by a promoter for the Dixie Circuit, one of NASCAR’s competitors. The promoter was looking for a Black driver to challenge the good ole boys at the track and asked Danville police if they knew of any prospects.

Thus began Scott’s professional racing career in 1951. Twelve days in, he won his first competition in Lynchburg, Va. He was denied entry into two NASCAR races before an official in Richmond gave him his NASCAR license in 1953, making him the sport’s first Black racer.

Racism was a constant. In Fredericksburg, Va., a spectator threw a lit firecracker at his son Wendell Jr., leaving a bloody wound on his hand. At a race in Savannah, Ga., Scott discovered someone had slashed his tires around the inside sidewall so that they wouldn’t go flat but would blow out during the race, putting his life in danger. After a race in Dover, Del., a spectator handed him a drink spiked with a hallucinogen.

One morning, while driving alone to a speedway in Rockingham, N.C., Scott came upon a Ku Klux Klan roadblock. He later said he believed the hooded figures waved him through because they didn’t realize he was Black due to his light skin.

There were also issues with NASCAR itself. NASCAR’s founder, Bill France Sr., had close ties with preeminent segregationist politicians, including Sen. Strom Thurmond (D-S.C.) and Gov. George Wallace (D-Ala.). Throughout his career, Scott was denied entry to races, scored and paid differently from White drivers, and subjected to needless additional inspections that disqualified him from races.

In “Hard Driving,” a 2008 Scott biography, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Brian Donovan makes the case that Scott should have been named rookie of the year for his 1961 debut at the Grand National level, now known as the Cup Series. Today, the commendation goes to the newcomer with the most points for the season, but back then it was more discretionary. That year’s winner had 3,580 points; Scott had 4,726. “Wendell Scott won it hands down,” NASCAR historian and journalist Gene Granger told Donovan.

Scott accomplished this using inferior equipment. As he could never find corporate backers to give him a proper car, Scott was constantly scrounging together whatever parts he could to make his car go.

“He faced a lot of challenges just to stay in the sport,” said Scott’s son Frank, 72, who believes he and his brother Wendell Jr.were the only Black pit crew chiefs in the history of the top level of NASCAR. (NASCAR says it doesn’t keep those records.) “It’s very expensive, and he didn’t have anybody paying his bills.”

Though NASCAR devotees were overwhelmingly White, Scott’s ability, determination and underdog status gained him many fans. By 1965, Scott could draw as much applause as his more famous competitors.

Jacksonville was the pinnacle of Scott’s career. After Baker was awarded the trophy, NASCAR officials held a two-hour closed meeting. Finally, Scott was told there had been a scoring error. He had won the race. There was no apology, no trophy and no ceremony, but he did receive the prize money.

In his book, Donovan quotes Mike Bell, a spectator whose father was friends with the NASCAR track promoter Julian Klein. According to Donovan, Klein told Bell’s father, “I wasn’t about to give that man the trophy and let him kiss the trophy queen. … I’d probably have had a riot at the racetrack if I had.”

NASCAR maintained for decades that it made an honest scoring error; it declined to comment on whether this is still its position.

“It’s obviously clear that Wendell Scott won the race,” said Brandon Thompson, NASCAR’s current vice president of diversity and inclusion. “Wendell was successful that night and really showed and proved that it doesn’t matter what color you are. If you can drive a racecar, you can drive a racecar.”

A few weeks after Jacksonville, at a race in Savannah, Scott was summoned to the scoring stand and presented with an inexpensive block of wood in lieu of the typical trophy for his Jacksonville win. He felt humiliated.

Late in his career, at age 51, Scott borrowed heavily so he could finally compete with a first-class vehicle.

His first race with his new car, a 1971 Mercury Montego, was on May 6, 1973, at Talladega, NASCAR’s largest and fastest superspeedway. Ten laps in, the engine of a competitor’s car blew, coating the backstretch with oil. Twenty-one racers crashed, including Scott, who totaled his car, damaged his right kidney, and broke his left leg, pelvis, right knee and three ribs.

He raced a few more times after the crash but never competed as consistently as before. He died in 1990 from spinal cancer.

Though it was slow to support Scott, NASCAR has worked to make amends in recent years.

In 2015, Scott was inducted into the NASCAR Hall of Fame. Two years ago, his family was given a replica of the trophy he should have been awarded in Jacksonville nearly 60 years earlier.

“Obviously, we wish it had happened sooner,” Frank Scott said. “It shouldn’t have taken that long for the family to get a replica of the trophy that he should have gotten 58 years prior, 2,045 races ago.”

NASCAR now celebrates Wendell Scott’s life on the first weekend of every March, with drivers putting a commemorative decal on their cars at a race in Las Vegas.

Efforts like these were pushed by the Wendell Scott Foundation, a nonprofit founded by Scott’s grandson Warrick that works to preserve his grandfather’s legacy and helps underserved students get an education. The foundation recently sponsored Rajah Caruth, one of two Black drivers currently competing full time in NASCAR.

In 2020, NASCAR made headlines when it banned Confederate flags at the track, a big decision for a sport so firmly tied to White Southern culture. NASCAR now has multiple diversity initiatives and hosts Bubba’s Block Party, free festivals aimed at reaching Black fans where attendees can meet Bubba Wallace, the only Black NASCAR driver to compete at its top level other than Scott. Wallace became the first Black driver since Scott to win a NASCAR race when he finished first at Martinsville, Va., in 2013.

Scott is also getting his due in Hollywood. Steven Caple Jr., director of “Creed II” and “Transformers: Rise of the Beasts,” confirmed via email that he’s working on a project about Scott, though he said he couldn’t disclose more details. “Like everyone who knew of Wendell, I was fascinated with how he handled himself on the track and how this black man broke barriers in an all-white sport,” he wrote.

Previously, Scott’s story was loosely adapted for the 1977 movie “Greased Lightning,” starring Richard Pryor and Pam Grier. He also inspired the character River Scott in “Cars 3,” voiced by Isiah Whitlock Jr. And Warrick Scott recently filmed an episode of “Kevin Hart’s Muscle Car Crew,” where he and the comedian discuss his grandfather’s legacy.

Though Scott was denied the widespread recognition he deserved during his lifetime, Warrick said his grandfather was constantly stopped by racing fans.

“Wherever he would go, somebody would recognize him,” Warrick said, adding that many of his most effusive fans were White. “People would start crying if they saw him or ask for autographs. He was like a phenomenon.”